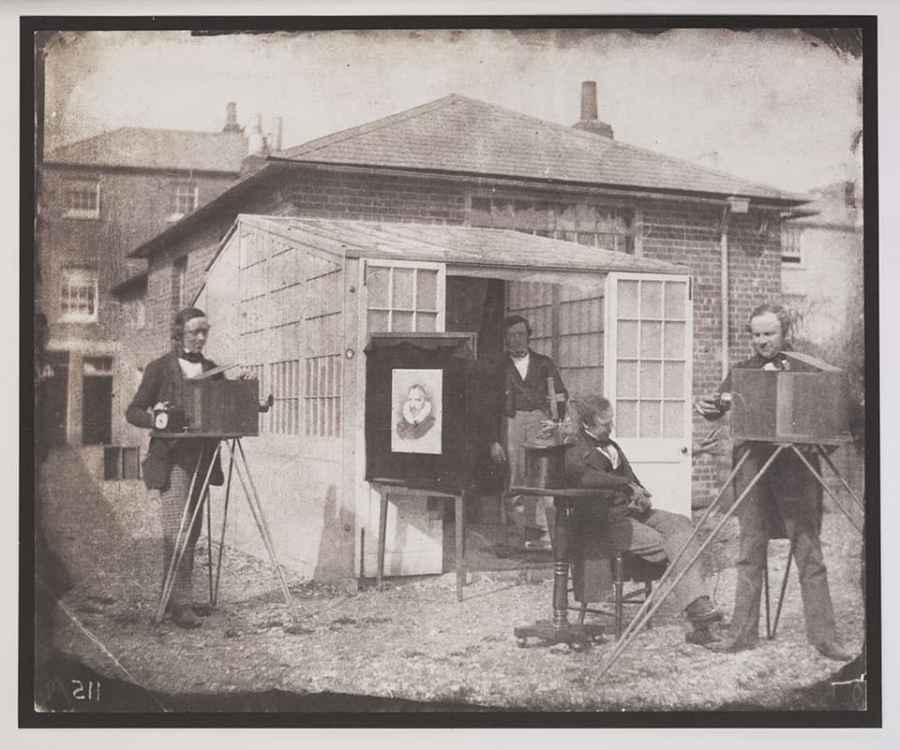

Talbot and Nicolaas Henneman at the Reading establishment, 1846 [© National Media Museum, Bradford]

‘Fox Talbot: Dawn of the Photograph’ charts the birth of photography within the industrial, cultural and social context of the 19th century. But publication of Fox Talbot’s photographic invention in 1839 may not have happened at all if it hadn’t been for Talbot’s mother and rivalry with Frenchman Louis Daguerre, according to the show’s curators.

Almost 100 of Talbot’s works will be on show alongside one of the earliest surviving photos by Frenchman Louis Daguerre, the Englishman’s chief competition in the race to reveal photographic inventions to the world.

Talbot wasn’t a natural PR man and, with one eye on the potential commercial success of his invention, it was his mother who spurred him into action – fuelled by competition from the other side of the Channel. ‘Talbot was enjoying photography and treating it as almost one of his many hobbies and interests, and there came a point at which he was compelled, largely by his mother, to do something that was going to be commercially successful,’ curator Greg Hobson told Amateur Photographer (AP).

The show taps into the ‘commercial imperative and industrial madness’ of the 19th century, added co-curator Russell Roberts. ‘You have to think what would have happened to photography if there wasn’t this impetus following the announcement by Daguerre… [Daguerre] was an important inventor of a photographic process which was kind of rarified and did make a lot of money but could not be assimilated into mass production.’

William Henry Fox Talbot by John Moffatt, 1864 [© National Media Museum, Bradford]

William Henry Fox Talbot by John Moffatt, 1864 [© National Media Museum, Bradford]

A large section of the show is devoted to The Pencil of Nature which Talbot published five years after announcing his discovery – the first commercial publication to be illustrated using photos.

Licence to use invention cost ‘£18,000’

Back then, photography was limited to the few who could afford it. And using one of the inventor’s processes was a tad more expensive than downloading the latest photography app.

It seems the rivalry between Talbot and Daguerre extended to the fees they charged for using their patented experiments. A licence to use Talbot’s invention, commercially, would cost someone the equivalent of ‘£18,000’ in today’s money, according to Hobson. ‘In Britain, one had to buy a licence to be a Daguerreotypist as well. It was free everywhere except in Britain, because Talbot insisted on charging a licence for his.’

Though amateurs would have to pay only £300, the extent of amateur use was limited by the sheer cost of equipment they needed. ‘What people would do is buy the amateur licence and attempt to use it [professionally],’ added Hobson.

Curator Greg Hobson (left) with co-curator Russell Roberts at the Science Museum this morning [© C Cheesman]

Curator Greg Hobson (left) with co-curator Russell Roberts at the Science Museum this morning [© C Cheesman]

The show also explores the relationships between the network of photographers who gravitated towards Talbot’s process and inspired them to experiment in different ways. These include Anna Atkins and Calvert Jones.

Asked how the show differs from previous Talbot exhibitions, Roberts told AP: ‘We’ve wanted to keep the romantic, early scientific sensibility, but it’s ultimately the industrial, commercial aspect of photography, which is often uncomfortable for certain historians and curators of photography because it doesn’t allow them to pursue the value of Talbot’s work as almost like a unique work of art [and] celebrate his subjectivity as an artist with a capital “A”.’

‘For us that is a small, incidental part… The art of photography that he describes in The Pencil of Nature is not art [as others defined it].

So, what would Talbot have made of today’s ‘selfie culture’, we wonder.

‘I think it’s weird to describe it as “selfie culture”,’ Hobson replied. ‘It’s an easy form to hang something on. I think what Talbot was moving towards was exactly where we are, which is this mass production and mass distribution of images… I think the only thing that would have surprised him is that people were able to use it so freely [using their smartphones].’

Roberts credits Talbot as setting in motion ‘a new way of seeing’, through his writings and experiments.

Speaking at a press preview earlier today, the Science Museum’s deputy director Jonathan Newby, said: ‘The real significance of Fox Talbot’s work was the invention of the negative–positive photographic process, the so-called “calotype negative”, which made possible positive prints using a simple contact printing process. It is interesting to note that this was a deeply scientific, chemical-based process but the word “calotype” derived from the Greek, meaning “beautiful impression”, so its artistic merit was recognised from the outset.’

Newby added: ‘The exhibition is testament to Fox Talbot’s magical and industrial vision of his invention which ranged from the capture of delicate natural specimens through to great ambitions that he had for photography as a mean of mass production.

‘And we need to consider… his contribution in the context of its social, cultural and industrial perspective of the times in which he lived.’

‘Fox Talbot: Dawn of the Photograph’ runs at the Science Museum until 11 September 2016.

The Open Door, late April 1844 [© National Media Museum]

The Open Door, late April 1844 [© National Media Museum]

Talbot’s daughter, Rosamond (1837-1906), c.1843 [© National Media Museum/SSPL]

Talbot’s daughter, Rosamond (1837-1906), c.1843 [© National Media Museum/SSPL]