From bribing KGB officers to standing in radioactive prison cells, Barry Lewis’s Siberian journey was anything but ordinary. His haunting photographs of Stalin’s Siberian Gulag are now gathered in a remarkable book.

‘We paid money to the KGB to get into a prison, about £700. We even had a receipt so we could claim it on expenses.’

In 1991, Lewis and writer Peter-Matthias Gaede arrived in Moscow on assignment for Geo magazine. It was the last days of Glasnost. Their mission: to photograph and interview survivors of the Gulag, the Soviet network of labour camps where 18 million were imprisoned between 1930 and 1953. Up to 1.7 million never came out.

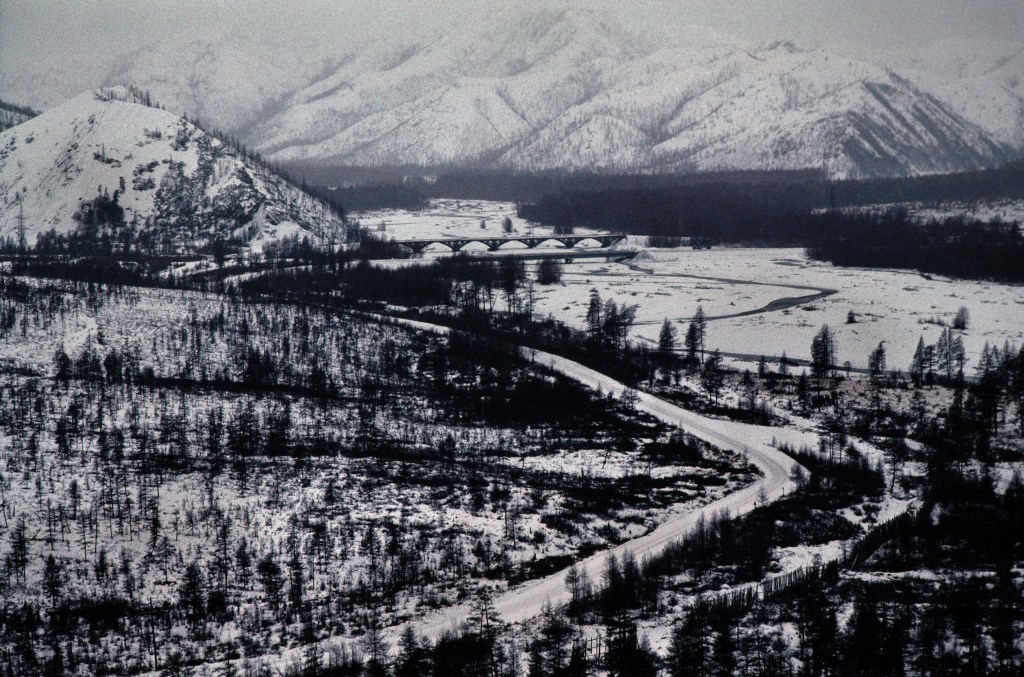

Road of bones

Their destination was Butugychag Corrective Labour Camp, hidden in the Kolyma mountains and disguised on maps as agricultural buildings. In reality, it was a uranium mine. ‘They used prisoners to build the 2000km Road of Bones. Many died. You couldn’t bury them in the permafrost, so the road was built over their bodies.’

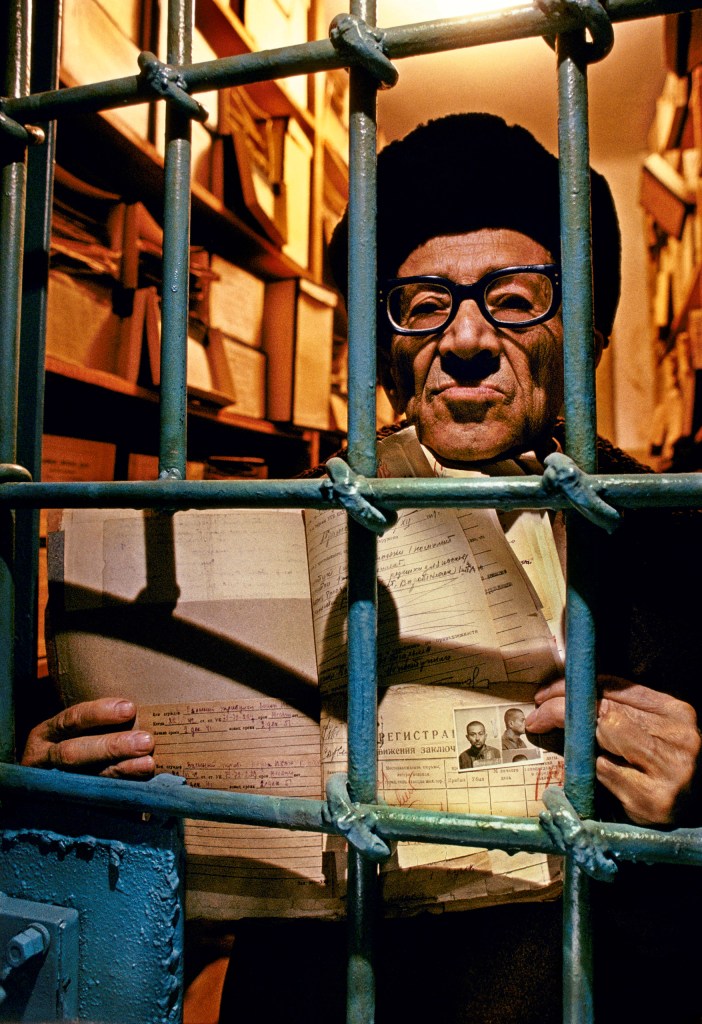

Dangerous access

First stop was Magadan, reached by a rickety Aeroflot flight. There, Lewis photographed prison survivor Asir Sandler, arrested in 1941 for carrying a book of forbidden poems. His death sentence was commuted to 25 years. Incredibly, in his old prison cell, now used for storage, he discovered his original arrest papers.

Inside the camps

With translator Vladimir Pyljov, Lewis gained rare access to Camp AV261/4, one of Russia’s 1,000 prison camps. Criminals had replaced political prisoners, but the brutality remained. ‘We’d arrive at 8.30am and leave by 9pm. Incredible access. I preferred not to use the translator, better to just hang out with the prisoners. I was even left alone with a murderer for about an hour.’ Barbed wire. Guard towers. Minus 30°C. The prisoners poured concrete outdoors, watched by guards who soon got bored of shadowing the British photographer.

Radioactive ruins

The journey ended in Butugychag. With a borrowed Geiger counter, Lewis discovered the mine was still dangerously radioactive. ‘Even the walls of the cells were radioactive. They didn’t just mine uranium, they processed it. That’s why so many died. In one section of the mine we could only stay 20 minutes.’ At one point a Soviet helicopter swooped down, suspicious of their presence. Once reassured, the crew even gave the journalists a lift back, circling low so Lewis could photograph the remote, snow-covered site.

Shooting in the freeze

Lewis relied on two Nikon FM2s loaded with Kodachrome 64 or 200, an 85mm, 50mm, 24mm and 180mm lens with x1.5 converter. ‘At -30°C the oils in the camera slow down. A shutter set at 1/125th is really closer to a quarter of a second. You listen, you bracket, you keep the cameras warm under your coat.’

From archive to book

From 35 rolls of film, Lewis created a visual record of prison survival and silence. Decades later, he discovered 200 more slides misfiled in his archive. Over 80 now feature in his new book, GULAG, published by Fistful of Books.