A comprehensive new biography of the ‘photographer nanny’ puts Vivian Maier into a new-found context. Author Ann Marks tells Amy Davies more about it

The work of Vivian Maier first came to widespread public attention in 2009, just a few months after her death. The detailed story of her life and discovery is discussed in a new all-encompassing biography. Photographing across a period which spans the ’50s to the late ’90s, most of Maier’s extensive – and disorganised – archive had been kept in various storage lockers in Chicago, where she spent the later years of her life. As a result of unpaid bills, the contents of the lockers went up for auction in late 2007.

Those purchasing the contents almost certainly had no idea of the superlative work they had picked up. The archive is estimated to include 140,000 photographs – with many more which were never developed. In fact, it’s said less than 5% of her captures were actually processed and printed during Maier’s lifetime.

One of the initial buyers, a local photo dealer named Ron Slattery, put some of the work up online, but it didn’t garner too much attention. Owing money to another collector friend of his, Jeffrey Goldstein, he paid him in Vivian Maier prints. Another buyer, John Maloof, who was working on a book of the local area at the time, also became interested in the photographs. Goldstein and Maloof now own the vast majority of the Maier archive between them, with the bulk in Maloof’s possession.

During the year and a half that Maier was still alive, while the images were first being tentatively shared online, several tried to find out more about her, though the notoriously private individual was impossible to find online. It was only after her death notice appeared in early 2009 that pieces of the puzzle started to come together.

After John Maloof published some of the photographs on Flickr in the well-known HCSP (Hardcore Street Photography) Group in October 2009, they quickly became a viral sensation. From then on the public was desperate to see more, and it has remained a fascinating story ever since. Such was the interest in Vivian Maier that not one but two high-profile documentaries were made about her. One of them, Finding Vivian Maier, was nominated for an Academy Award in 2015.

Despite the attention, there remained little knowledge about Maier’s history and background. Some of those who had known her while she lived in Chicago had been contacted prior to the making of Finding Vivian Maier, but large swathes of her life were simply not known about, and had hitherto proven difficult to investigate. This is where author Ann Marks comes in.

She tells me, ‘I went to see Finding Vivian Maier, and I just couldn’t stop thinking about it – all the questions that were unanswered, and the different ways people described her – which were often complete opposites. I started to look into her, but the more I did that, the more questions I had. I contacted the people involved with her [Goldstein], offering to help understand her background.’

It may surprise some to learn that Ann’s background is not in photography. In fact, she spent 30 years as a senior executive in large corporations, serving as chief marketing officer of Dow Jones/The Wall Street Journal. Upon retirement, her research and analytical skills have been put to good use and she has now spent several years delving into the life and mysteries of Vivian Maier. She explains, ‘Photography is my favourite art form, but I’m an amateur. Of course I loved her photos, but because people had found out so little about her I felt like if we understood her we could understand her work better.’

At the time of the initial set of images being released, and likely cemented by the documentaries, the overall impression of Vivian Maier was that of a reclusive oddball, with no personal desire for her own work to be seen, nor any ambitions to progress beyond amateur photographer status. However, as with most things in life, there seems to be a lot more to Maier’s story.

Ann’s extensive and often-times painstaking research tells of a troubled upbringing and difficult family story for Vivian Maier, with many issues that would remain throughout her life. The challenges of finding this information were numerous, as Ann explains: ‘They had used a genealogist and still found very little. It’s so tedious, you have to be someone who’s going to do this for free really. One of the challenges was that Vivian’s family was very secretive, so they falsified most records.

‘When you’re first starting out, you don’t realise that when you find two conflicting things, it’s because they’re doing it on purpose. Once I’d realised that, it became easier to find the facts and sort through them. The first project I got was to find Vivian’s brother because at the time they were trying to find the heirs. No one had any record of him after 1942. I thought he might be the key to opening up all the other records in the family – and he was.’

Such was the interest in Maier, particularly in her adopted hometown of Chicago, that the revelatory discovery of her brother Carl’s records landed Ann on the front page of the Chicago Tribune. From there she was contacted by John Maloof, the owner of the bulk of the Vivian Maier archive, and given unprecedented access to its contents in order to put together as definitive a biography as possible.

In the book, we find out that although it’s Chicago where much of the Maier interest is centred, it was actually New York where it seems she tried – and ultimately failed – to pursue photography as more than just a hobby. Her work as a nanny gave her the free time and flexibility to capture life on the streets of mid-century New York in a way which has come to be recognised as some of the finest work of the period.

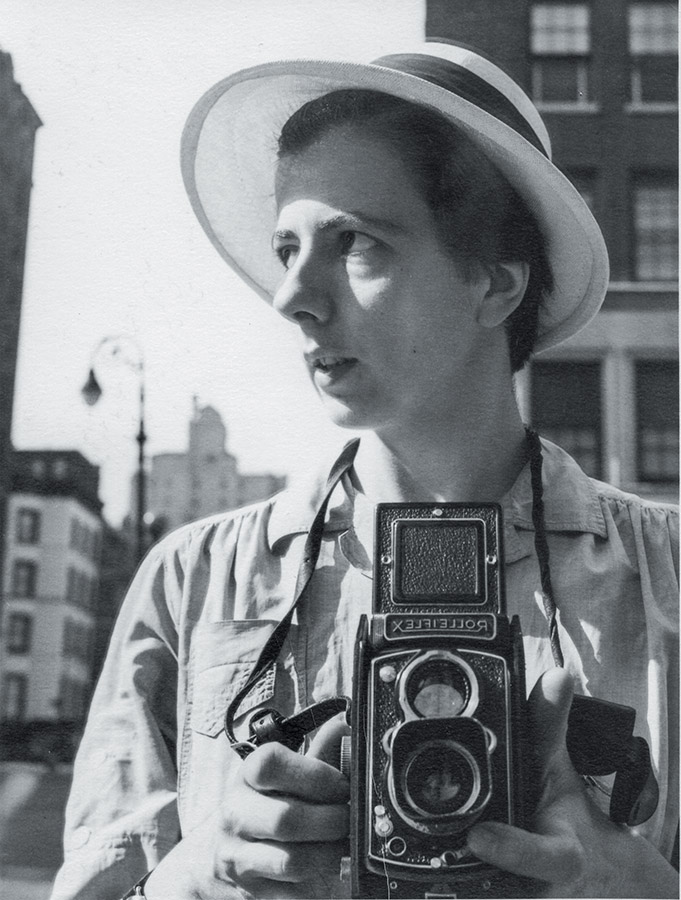

It was also here, aged 26, that she purchased a Rolleiflex – an indicator of how serious she was, it being a camera used primarily by professionals.

Maier was never known to have any formal training in photography, but her efforts to integrate with the photographic community were pursued most in earnest in the years up to 1955 while living in the city. She spent her free time observing other photographers, pursuing celebrities in a paparazzo-style fashion, and even taking posed portraits.

At one point she also tried to set up a postcard business. She was far from being shy or unsure of her talents – her employers seemed to know all too well her abilities, commissioning her (likely unpaid) to cover important family events.

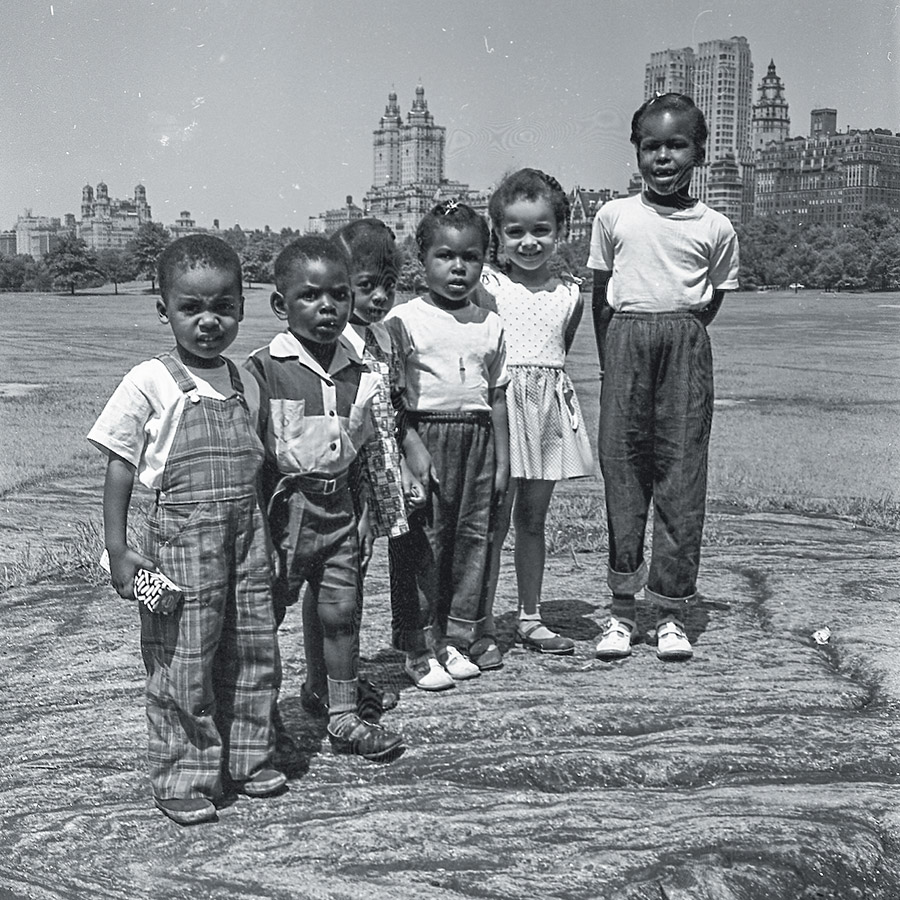

Maier’s skill seems to be what gives her broad universal appeal, even today. That, alongside her authenticity and her progressive approach to her subjects. Ann says, ‘You see things and it evokes an emotion. For instance, at the time, nobody was taking photographs of children in their natural state – crying, or yelling.

A shot from Chicago in 1961, one of many which displays Maier’s fondness for collecting typefaces in her images

Her authentic photographs make you think of your own kids – or even yourself. She was also kind of agnostic when it came to race, gender, religion. Even from the earliest photographs in 1950 we can see she was taking pictures of African-American young professionals, and Anglo and African Americans playing together. This was ten years before the civil rights movement in this country.’

Critics have praised Maier’s work, mentioning her in the same breath as masterful contemporaries including Dorothea Lange, WeeGee, Helen Levitt, Saul Leiter, Diane Arbus and Robert Frank. Her fantastic hit rate has been commented on, with many reflecting on her superb skill to see a moment, capture it and move on quickly to the next.

One of her child charges, Inger Raymond, accompanied Maier on several of her photographic walks, and is quoted in the book: ‘She would see a subject, open her camera, focus it, and she’d snap. It was fast. She went from walking to focus to shoot in under a second. The subject wouldn’t even have time to react.’

As well as uncovering historic records, Ann was able to track down and interview more than 30 people who had actually known Maier, to get a better idea of what she was like. Such was Vivian’s character, that it seems she is remembered vividly by almost everybody who encountered her. Most recall a woman who had an unforgiving and at-times unsettling demeanour.

It’s summed up by the quote from the book, ‘Wherever Vivian went she was always noticed, but almost never known or understood.’ Modern sensibilities would likely have much more sympathy for a woman who at the time was often dismissed simply as strange. It’s easy to look at one of the many self-portraits of this severe-looking character (more than 600 have so far been uncovered in her archive), and assume many things. Luckily for Ann, she had something else to go on – among the possessions found in the storage lockers were audio tapes, containing recordings made by Maier, who would often conduct mock interviews with acquaintances.

‘One of the biggest epiphanies was when I listened to Vivian’s tapes,’ says Ann. ‘She was completely different than I thought she would be. People thought her humourless, a little bit stern – but in fact, she’s hilarious, she’s lovely, she’s warm. It’s her physical presence which could be off-putting, but on hearing this I had this human connection with her.’

It’s clear that Maier too shared a similar connection, if not with all she met, at least with her subjects. Her photographs reveal more about her personality than her outward appearance ever could. Indeed Ann notes in the book, ‘Many have noted the irony that a woman who had such difficulty expressing herself in person could produce photographs so full of openness, feeling and humanity.’

A self-portrait of Vivian Maier, taken in New York, 1954. She is seen holding her beloved Rolleiflex

Ann was the first person to find people in New York who had known Maier, where it seems her character was somewhat different from the older, more cut-off persona she adopted on moving to Chicago. Such was the difficulty in tracking down these people, with little more than a last name here, or a decades-old address there, that there’s an appendix in the book detailing some of her pursuits.

In our chat, Ann tells me a little more about one of them. ‘She took a photo session of three sisters, and the mother and father on a rooftop. It seemed to me to be her first proper portrait sittings, and she also seemed to be friends with them. I felt I’d have a lot of information about her early photography if I found them.

What I had to do was try to figure out where the rooftop was – it took me a whole year to figure out that the picture was flipped and so all the buildings on the west were actually on the east. Once I’d managed to triangulate it, I discovered that one of the sisters was in her 80s and remembered everything.’

In the book, it’s posited that Maier is likely to have suffered from several personal and mental problems, most notably a hoarding disorder – something which seems obvious from the stacks of personal possessions left behind in disarray and confusion, and the debts which led to her archive being discovered.

Making assumptions about somebody who is no longer here to argue otherwise is naturally fraught with potential issues. It’s something that was faced by those who initially published her photographs, with some suggesting that she may not have wanted her archive to be seen, much less for there to be discussions about her life and background.

Looking though somebody’s private possessions might feel objectionable, but those same posessions seem to reveal that Maier is unlikely to have minded too much. Ann says, ‘She was very fatalistic – she thought once you’re dead, you’re dead and it’s for others to make decisions. And remember she was very much into celebrities – she chased them her whole life. I actually think maybe she would have liked to have been a celebrity herself – I don’t think she would have hated it anyway.’

It’s also important to consider that Maier clearly showed little or no regard for the privacy of others in pursuit of some of her work. The book includes clippings from a newspaper article (kept by Maier herself) detailing her arrest for trespass on the scene of a murder in an attempt to get a better vantage point.

Her street scenes show she was not afraid to get up close and personal in the name of a good shot, while she was fearless in situations that might test the bravery of even hardened career photojournalists. Ann says in the book, ‘The fight to protect Vivian’s privacy is perhaps the most ironic twist of all. She was the last person in need of protection.

While private in regard to her background, Vivian espoused her opinions and impressions boldly. She had minimal respect for the privacy of others. Her pictures depicted people at their very worst: the vulnerable, distressed and passed-out subjects would have undoubtedly objected to her intrusion if given the chance.’ Accusations of profiteering have also long-followed the archive holders, something which is keenly rebuked and reflected on in the book, too.

In an archive where only 5% of the material has been printed by the photographer, who left no will, no instructions or arrangements for her belongings or posthumous wishes, much has also been discussed in terms of how the remainder should be processed, and who gets to make decisions about aspects such as cropping.

In an attempt to gain an understanding of what Maier might have wanted, those charged with the task looked extensively at how she approached those which she did select. As you’ll see if you look through the book, different decisions are made throughout her archive. As a result, any new images are printed as they were shot, but, such is Maier’s obvious keen and precise eye, the resulting frames do not suffer from it.

Similarly, making decisions about what to include in a book – even one which includes more than 500 pictures, a mere fraction of such a vast archive – was of course difficult. ‘What I wanted to do was tell her life story and place her photography in context, so I wrote the narrative and then supported it with photographs.

It wasn’t easy but I chose the photographs based on that. Before this, no one had had access to the entire archive, so no one saw her work chronologically. I could therefore trace her development.’ Ann also wanted to make sure that the book did justice to Maier’s work. As such, it is printed entirely on glossy paper – unusual for a biography – and much time was spent on the look of the finished product.

So far, reaction to the book has been almost entirely positive – some will argue that ascribing diagnoses of mental health conditions on those no longer living is problematic. Overall however, it’s been a success – so much so that the initial print run in the US completely sold out.

As for Maier, at the end of a decade which saw her shoot 500 rolls of colour film but process none of them, Vivian finally hung up her camera in 1999, just shy of a decade before her death in 2008 aged 83.

Such is the complexity of Maier’s story that this feature you’re reading – and arguably even Ann’s 350-page book, fascinating as it is – only scratches the surface. It seems like there will always be new discoveries to be made about this elusive character. ‘At one point I felt like I was spending more time on Vivian’s life than my own, so I actually made myself stop,’ says Ann.

‘Even after the book was published I’ve already found a few really key things which I wish had been included in the final edit. For now, I do a lot of talks, interviews and so on. I’m kind of just trying to keep Vivian in the public eye and create a deeper understanding of her work. You can look at it very differently if you want to, from knowing her life story.’

We’ll never truly know what Maier would have made of the attention her archive has garnered – but Ann is highly optimistic. ‘We can only hope that Vivian Maier’s real dreams and desires have in some way come true.’

For much more fascinating detail about the intriguing life of Vivian Maier, the book Vivian Maier Developed: The Untold Story of the Photographer Nanny by Ann Marks is available to buy now. RRP £28. ISBN: 9781982166724.

Further reading:

Best photography exhibitions to see in 2022

Secret life of photographer Vivian Maier turned into DVD film

Fill the Frame documentary explores social media’s influence on street photography