A long-running copyright dispute between photographer Lynn Goldsmith and the estate of Andy Warhol, over use of Goldsmith’s images of the late music superstar Prince, will be heard by the US Supreme Court later this year.

On Monday 28 March 2022 the Supreme Court agreed to hear the case as the final stage in an ongoing legal battle that dates back in 2017.

The question before the Supreme Court will be whether Warhol transformed the image enough that it had a distinct meaning or whether the artwork violated Goldsmith’s copyright.

Lynn Goldsmith, left, and the late Andy Warhol, right

It’s a twisting and intriguing saga that involves a dead global music superstar, a photographer who has shot over 100 album covers in her lifetime and the big question of IF the late Andy Warhol’s iconic artworks are in violation of photographic copyright.

Read on to find out more…

Original 1981 photo shoot

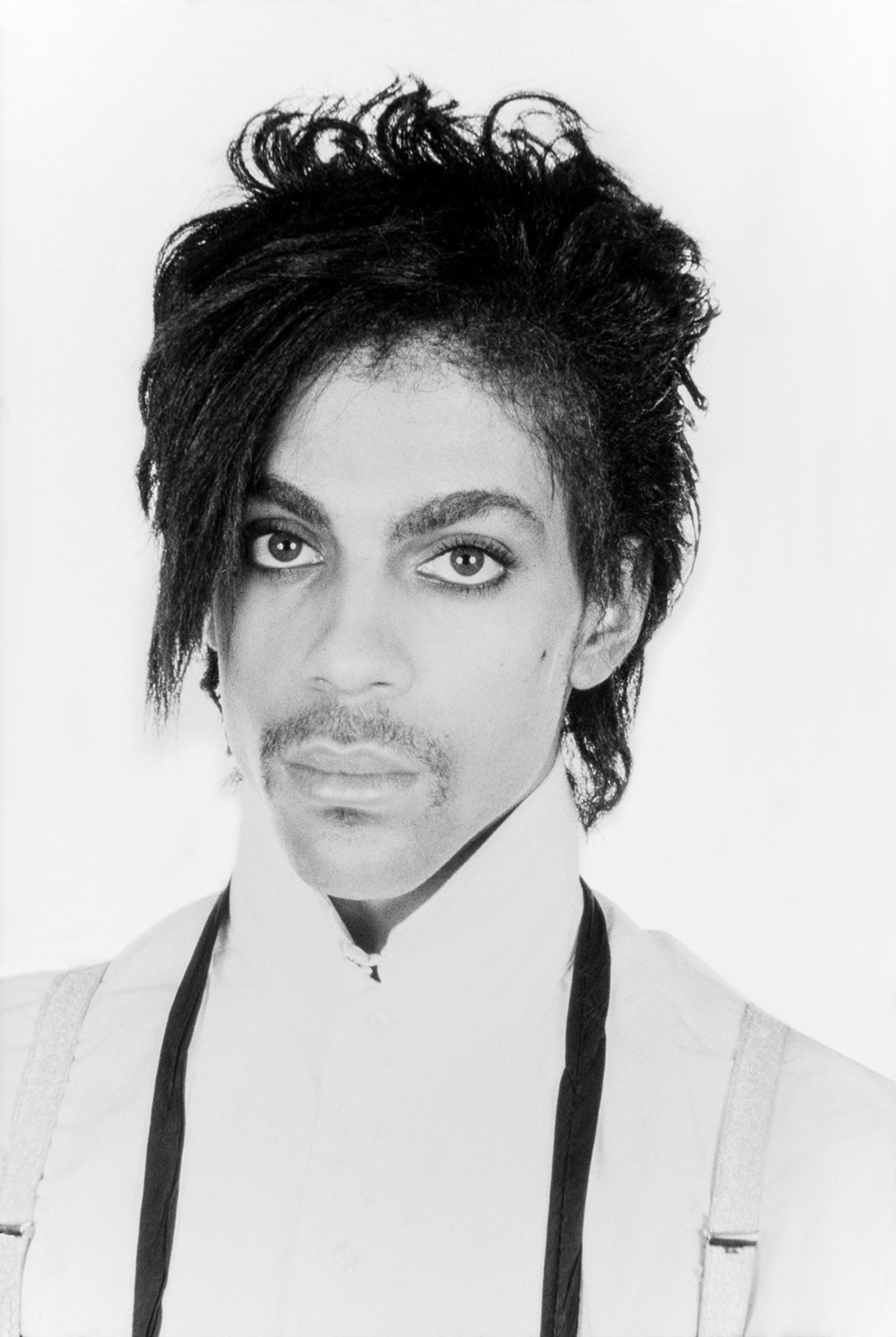

The roots of the case date back to December 1981 when Goldsmith did a photo shoot, while on assignment with Newsweek, with the then relatively unknown musician Prince. The images were not published at the time.

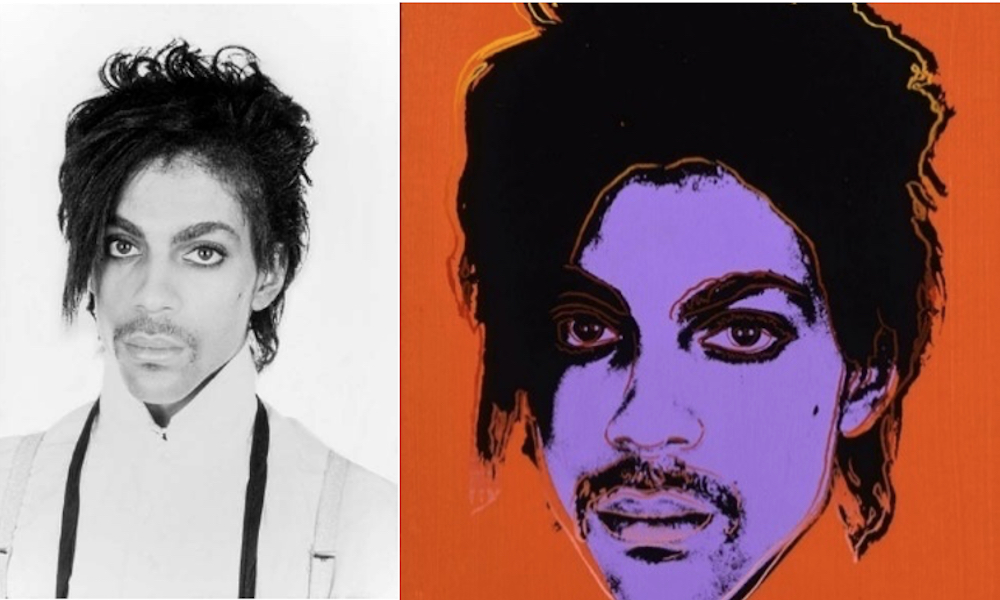

Three years later, in 1984, when Prince’s Purple Rain album made him a global superstar the magazine Vanity Fair licensed one of Goldsmith’s black-and-white studio portraits for $400.

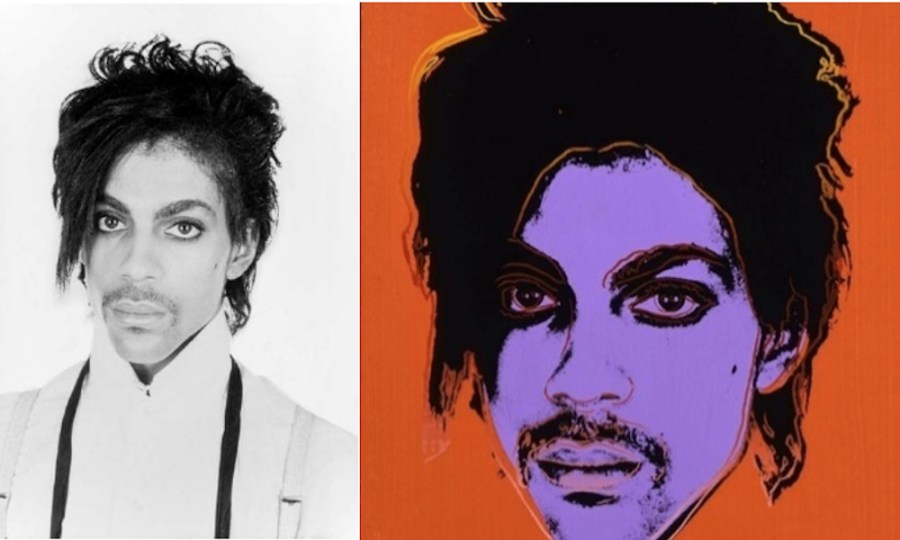

One of Lynn Goldsmith’s original 1981 black and white images of musician Prince

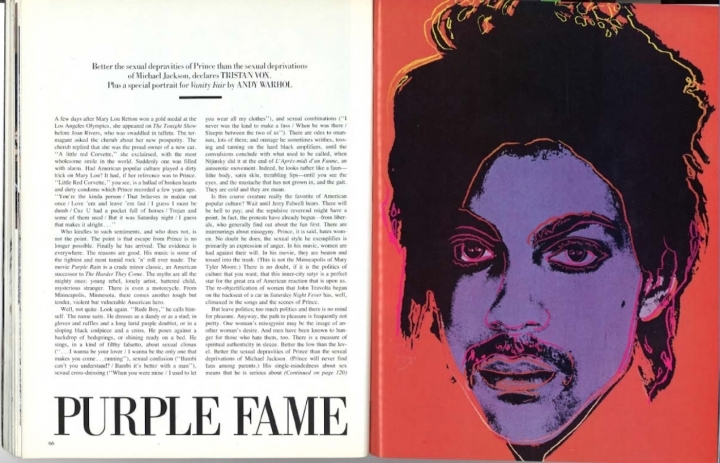

It commissioned Andy Warhol to create artwork for a feature on Prince that was published with the title Purple Fame.

Warhol used a cropped photo based on one of Goldsmith’s images from the 1981 shoot to create one of his artworks.

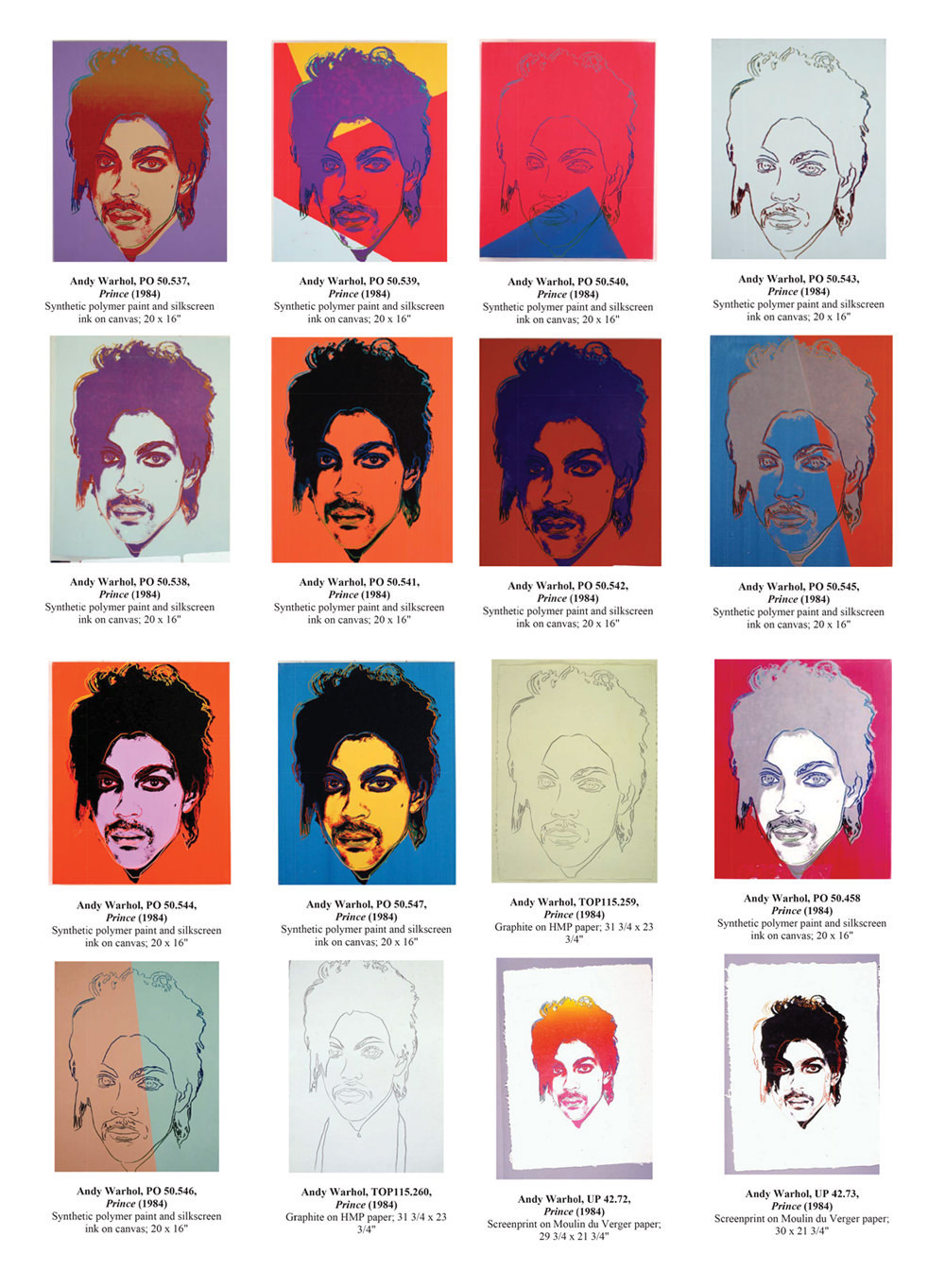

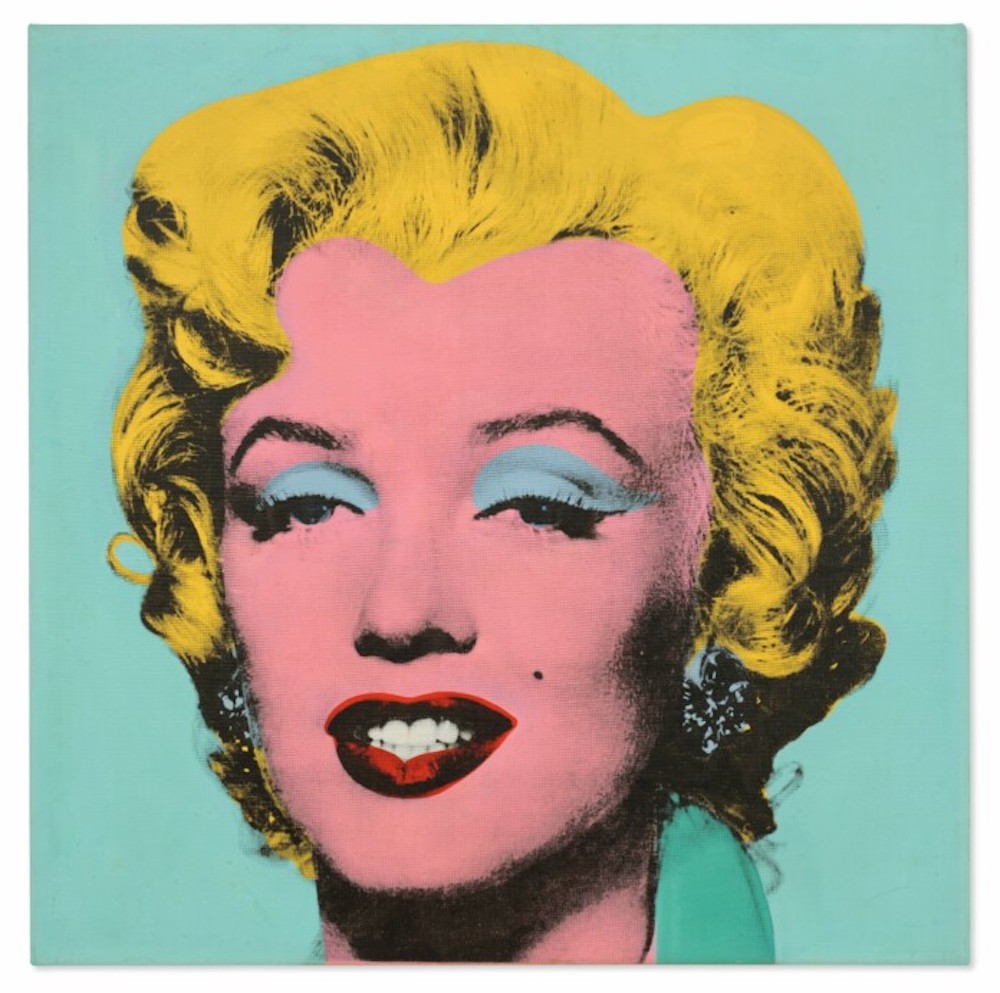

He later produced a series of 16 variations – 12 silkscreen paintings, two screen prints on paper and two drawings – much like he had done with portraits of actresses Marilyn Monroe and Liz Taylor in the 1960s.

The start of the Purple Fame article in Vanity Fair, 1984

Goldsmith was unaware of this use of her photograph of Prince until after the music superstar’s death in April 2016.

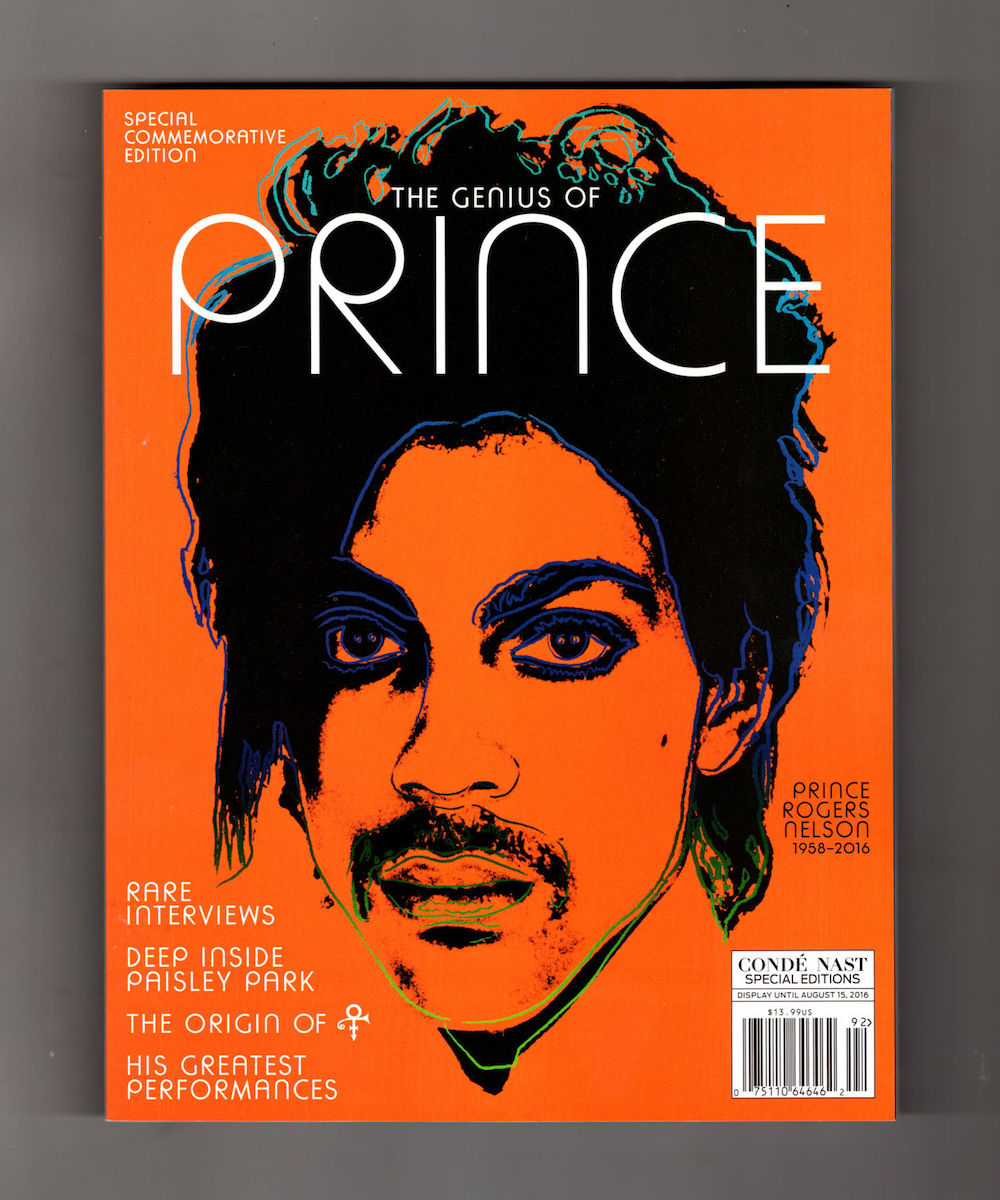

The dispute emerged after Prince’s 2016 death, when the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts licensed the use of Warhol’s so-called ‘Prince Series’ for use in a magazine commemorating Prince’s life.

One of Warhol’s creations was on the cover of a special The Genius of Prince magazine, published by Vanity Fair‘s owners Condé Naste in May 2016, with no image copyright credit to Lynn Goldsmith.

The Genius of Prince magazine cover from 2016

Goldsmith claimed that the publication of the Warhol artwork destroyed a high-profile licensing opportunity.

Pre-emptive legal move

In April 2017 the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts filed a pre-emptive legal strike by suing Goldsmith and asking the court to declare that Warhol’s 1984 paintings of Prince didn’t violate Goldsmith’s copyright as they were ‘entirely new creations.’

Goldsmith filed a counterclaim declaring that Warhol’s work wasn’t ‘transformative’, and that ‘anyone can easily modify a photograph on a computer to add high contrast, colour and artefacts.’

In a July 2019 a US District Judge in Manhattan, John G. Koeltl, put aside a judgement that the Andy Warhol Foundation works were of ‘fair use.’

Judge Koeltl concluded that Warhol transformed a picture of ‘a vulnerable and uncomfortable’ Prince into an artwork that made the singer an ‘iconic, larger-than-life figure.’

The 16 artworks created by Andy Warhol based on a 1981 Lynn Goldsmith photograph of Prince

Appeals Court sides with Goldsmith

Then, on 26 March 2021, a three-judge panel in the New York-based US Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit reversed the 2019 ruling and sided with Goldsmith.

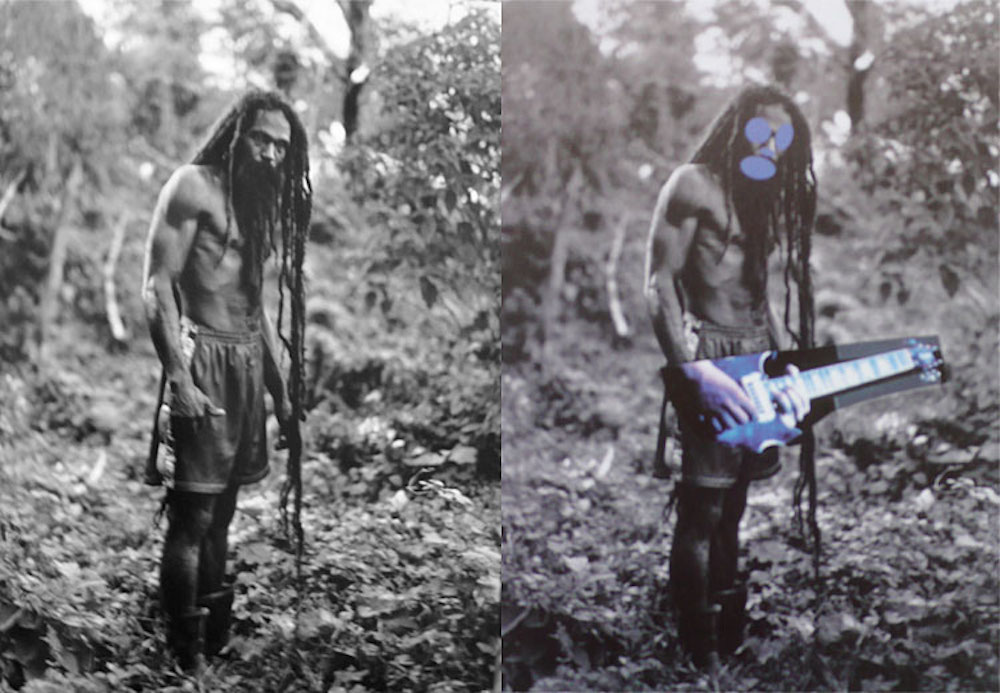

In making that ruling the court had cited the previous controversial Circuit Court’s 2013 ruling in the Cariou v. Prince case.

That ruling decided that appropriation artist Richard Prince had not violated photographer Patrick Cariou’s copyright by altering photographs from Cariou’s 2000 book, Yes, Rasta, for the 2008 series of paintings known as Canal Zone.

A Patrick Cariou photo, left, versus a Richard Prince artwork, right

Cariou had originally brought the case in 2009 and appealed the 2013 verdict, with the two artists eventually settling out of court.

In essence that 2013 case had, at the time, helped to strengthen the arguments of those artists who argued ‘fair use’ when using photographs as a basis for paintings or artworks.

Indeed, in 2013, both the Warhol Foundation and the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation filed briefs in support of Richard Prince.

Their argument was the intellectual content and aesthetic meaning of works of art are not always visible to the naked eye without art-historical context.

Their brief suggested that art historians, curators and other experts should have a say in that case.

The ruling

To return to Goldsmith case… on 26 March 2021 the Circuit Court ruled that the Warhol series was ‘substantially similar to the Goldsmith photograph as a matter of law’ and sent the matter back to the District Court for further proceedings.

The Second Circuit Judge, Gerard E. Lynch, in a written decision said, ‘Crucially, the “Prince Series” retains the essential elements of the Goldsmith Photograph without significantly adding to or altering those elements.’

A concurring opinion written by Circuit Judge Dennis Jacobs said the ruling would not affect the use of the 16 ‘Warhol Prince’ series works acquired by various galleries, art dealers, and the Andy Warhol Museum because Goldsmith did not challenge those rights.

The three-judge Second Circuit panel said its ruling should help clarify copyright law. It cautioned against judges making ‘inherently subjective’ aesthetic judgments, saying they ‘should not assume the role of art critic and seek to ascertain the intent behind or meaning of the works at issue.’

The appeals court repeatedly compared the copyright issues to what occurs when books are made into movies. The movie, it noted, is often quite different from the book but yet retains copyright obligations.

The appeals court also said the unique nature of Warhol’s art should have no bearing on whether the artwork is sufficiently transformative to be deemed ‘fair use’ of a copyright, a legal term that would free an artist from paying licensing fees for the raw material it was based on.

Lynn Goldsmith’s original 1981 photo of Prince, left, versus the Warhol artwork, right

Judge Lynch ruled that to be a transformative use, he added, the new work must offer ‘something more than the imposition of another artist’s style on the primary work.’

He compared Warhol’s distinctive silkscreen aesthetic to a filmmaker with an easily identifiable style turning a book into a movie – that doesn’t mean the film is no longer a derivative work.

The Circuit Court also advised, ‘It does not follow, however, that any secondary work that adds a new aesthetic or new expression to its source material is necessarily transformative.’

The circuit court in the Goldsmith appeal, said it found that the ‘Prince Series’ is likely legally derivative, and that both artworks serve the same function as a portrait of the singer.

The appeal court said, ‘We feel compelled to clarify that it is entirely irrelevant to this analysis that “each Prince Series work is immediately recognizable as a Warhol”. Entertaining that logic would inevitably create a celebrity-plagiarist privilege; the more established the artist and the more distinct that artist’s style, the greater leeway that artist would have to pilfer the creative labors of others.’

Reaction to the ruling

Following the Appeal court ruling a Warhol Foundation attorney, Luke Nikas, said, ‘Over 50 years of established art history and popular consensus confirms that Andy Warhol is one of the most transformative artists of the 20th Century. While the Warhol Foundation strongly disagrees with the Second Circuit’s ruling, it does not change this fact, nor does it change the impact of Andy Warhol’s work on history.’

Attorney Barry Werbin, who represented Lynn Goldsmith, called the ruling, ‘a long overdue reeling in of what had become an overly-expansive application of copyright “transformative” fair use. The decision helps vindicate the rights of photographers who risk having their works misappropriated for commercial use by famous artists under the guise of fair use.’

In a statement after that ruling Lynn Goldsmith said the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts wanted to, ‘use my photograph without asking my permission or paying me anything for my work. I fought this suit to protect not only my own rights, but the rights of all photographers and visual artists to make a living by licensing their creative work – and also to decide when, how, and even whether to exploit their creative works or license others to do so.’

Lynn Goldsmith self-portrait, Friday 26 March 2021

The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts argued that the ruling, ‘casts a cloud of legal uncertainty over an entire genre of visual art and would threaten “a sea-change in the law of copyright”.’

Warhol Foundation petitions Supreme Court

In May 2021 the Andy Warhol Foundation then filed a petition with the US Supreme Court to decide, ‘Whether a work of art is “transformative” when it conveys a different meaning or message from its source material, like this Court, the Ninth Circuit, and other courts of appeals have held, or if a court is forbidden from considering the meaning of the accused work where it ‘recognisably deriv[es] from’ its source material (as the Second Circuit has held).’

The Andy Warhol Foundation’s petition to the Supreme Court argued, ‘Under this Court’s precedent, the fair use inquiry requires ascertaining whether one creative work that draws from another conveys a different meaning or message from the original. A follow-on work that deploys pre existing content in the service of saying something new and distinct is much more likely to be fair use. The Second Circuit’s test, however, forbids ascertaining whether the follow-on work conveys a different meaning or message from the original, where both pieces are works of art that share a visual resemblance.’

Requirements in US law

In US law, appropriation or using someone else’s image in an artwork is allowed, so long as it isn’t exploited for commercial use.

In other words, you could make an artwork from a portrait photograph and hang it on your walls at home, but if you then decided to exhibit or sell versions of that artwork you could be open to legal action based on the fact you were seeking to exploit it for commercial reasons.

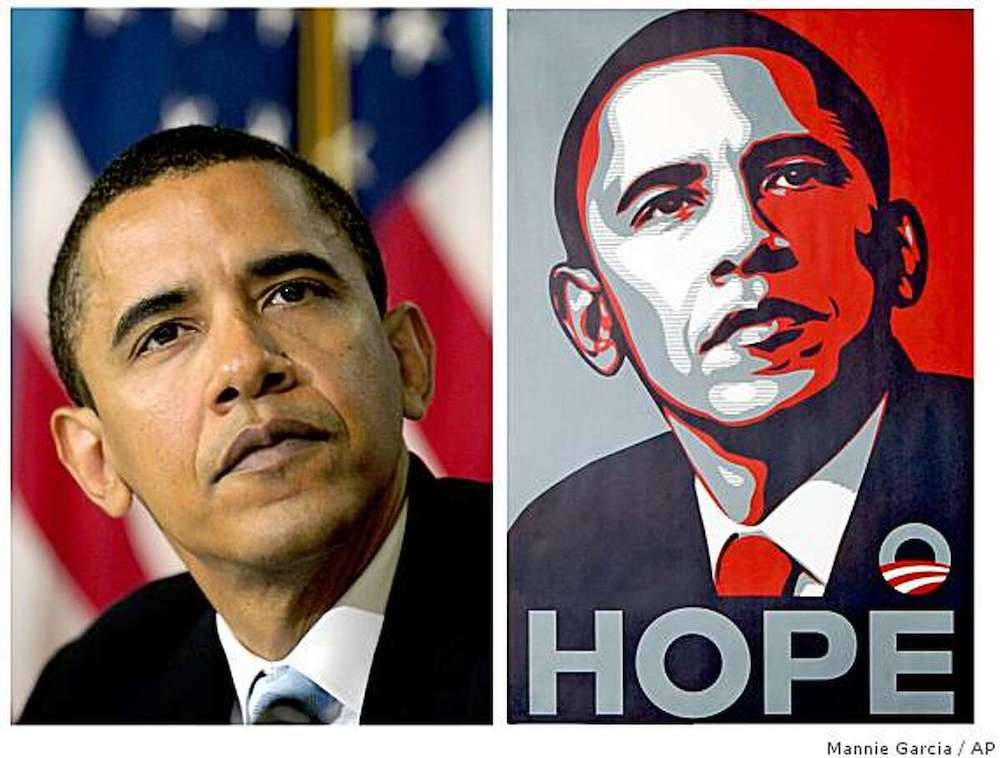

In the case of artist Shepard Fairey, who licensed artwork of the famous Barack Obama HOPE poster to Urban Outfitters, the artist was in breach of copyright as the image of Obama, shot in April 2006, belonged to the Associated Press freelance photographer Mannie Garcia.

The Mannie Garcia photograph, left, shown alongside the Barack Obama HOPE poster by Shepard Fairey

In January 2009, after Obama had won the 2008 US Presidential Election, Fairey’s stencilled portrait version of the image was acquired by the Smithsonian Institution for its National Portrait Gallery.

Later that month, the photograph that Fairey based the poster on was identified and the Associated Press then began negotiations for compensation.

Fairey sued for a declaratory judgment that his poster was a ‘fair use’ of the photograph. The parties settled out of court in January 2011.

In February 2012 Fairey pleaded guilty to destroying and fabricating evidence showing that he had used the photograph.

In September 2012 he was sentenced to two years of probation, 300 hours of community service and fined $25,000.

Possible consequences

The US Supreme Court is expected to hear the Goldsmith v Warhol Foundation case during autumn 2022, but no specific date has been set yet.

Should the Supreme Court rule in favour of Lynn Goldsmith it will likely strengthen the cases of all photographers for any future similar copyright disputes.

It has also raised a whole new area of the legality of appropriated material used in artists’ paintings, sculptures and prints.

It could potentially open up a myriad of legal questions for the Andy Warhol estate as Warhol made a career taking other peoples’ photographs – like those of Marilyn Monroe, Liz Taylor and Jackie Kennedy – and making them into artworks.

Shot Sage Blue Marilyn by Andy Warhol is expected to fetch around $200million at auction at Christie’s in May 2022

In monetary terms, this is very, very big business…

For example, a 1964 Marilyn Monroe silkscreen Shot Sage Blue Marilyn by Andy Warhol – based on a promotional photograph for her 1953 movie Niagara – is up for auction at Christie’s New York in May 2022.

It is tipped to fetch around $200million – if it sells for that price, it will become the most expensive artwork produced in the 20th century.

Find out more…

To discover more about the work of photographer, filmmaker and musician Lynn Goldsmith go to the Lynn Goldsmith website.

Related articles:

Rap superstar Snoop Dogg wades into photo copyright row (NSFW)