The macro setting

The macro setting

Tucked into the exposure mode dial or perhaps in the subject selection bar in a digital camera menu, there is often a flower symbol.

If you own an older Canon lens it may be found on the barrel, together with a number in metres or feet.

The flower is the international symbol for a close-up and the number is the nearest focus distance of the lens.

The measurement is that from the film or sensor image plane in the camera, not from the front rim of the lens, to the subject. The image plane is usually marked on the left of the top plate, but is not always present on digital cameras, and it only becomes important in technical work.

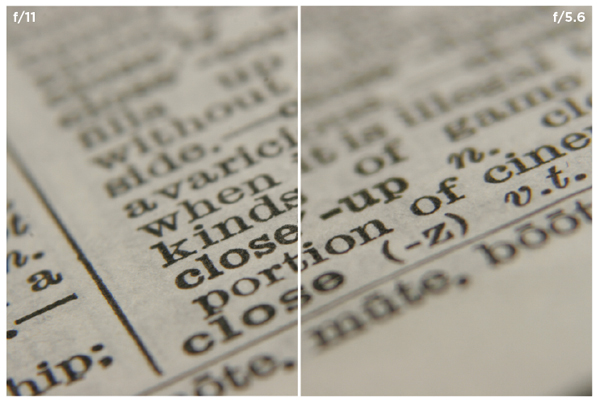

When set to this close-up mode, the tendency is for the camera to use a lens aperture to give shallow depth of field. This isolates the subject against a diffuse background since depth of field is limited in close-up anyway.

Macro lenses

Lenses and kit designed for close working are often called macro, as in a macro zoom. However, the purist will point out that macro is really applied when the size of a subject’s image is bigger than the subject, up to 10x its size.

In photography, any lens that can focus closer than you might expect tends to be called macro. The label is often attached to zoom lenses, which are called zoom macro or macro zoom lenses.

A monofocal (or fixed focal length) lens that has the macro label will usually focus close enough for the subject and its image to be the same size. Yet zoom lenses fall short of that, as they focus mostly at about half size.

Repro scale

The size ratio between subject and image is termed the reproduction, or repro, scale, or given as a magnification factor.

Same size is a 1:1 repro scale, for example, and half size is 1:2. Just put the first figure over the second to give the fraction of image to subject size.

Rated as a magnification, 1:1 is 1x and 1:2 is 0.5x. For most close-ups, the actual repro scale or ‘x factor’ is far less important than the composition of the picture.

Zoom lenses

The reason zoom lenses do not focus down to 1:1 is that the optical corrections governing image quality are difficult to maintain when close in while at the same time maintaining them over the range of focal lengths.

In fact, they are rarely free of one error when at close quarters, which is curvilinear or drawing distortion. This is the bending or bowing of straight lines in the subject. It means that these lenses are not good at taking pictures of buildings or for copying documents, drawings and pictures.

However, this leaves the whole of the natural world wide open for taking subjects, both living and still.

However, this leaves the whole of the natural world wide open for taking subjects, both living and still.

A macro telephoto zoom at its top focal length is ideal for taking nature pictures.

It allows a close-up to be taken from a distance at which a live subject won’t become aware of you.

Macro monofocal lens

Once the photographer is hooked on close-ups, it is time to consider upgrading to a macro monofocal lens able to focus to 1:1.This opens up a further and fascinating field of opportunity in nature photography.

Also, since these lenses are well corrected for distortion, architecture and other linear subjects will be accurately rendered when shooting at middle and far distances, at which it remains well corrected.

The copying of documents, old photographs and so on can also be undertaken. Selective enlargement of a section of a shot taken at, say, 1:2 will give the impression of one at 1:1, but the quality of colour and detail will not be as good as from a 1:1 lens.

A plus point of close-up work is the fact a photographer has time to consider the lighting, camera angle and composition.

Such freedom is at its greatest in table-top photography. This is the equivalent of still life in painting – objects are chosen and arranged to satisfy the photographer’s creative skill. Overall, close-up photography is a fascinating genre which, once tried, usually becomes a lifetime pursuit.

Image: At 1:1 reproduction, the details of everyday objects take on new significance

Macro is the Greek word for ‘big’ and has come to mean any lens that can focus down to a close-up of a subject.

In optics the term has a very specific meaning. In general photography, we image the subject much smaller than its actual size. You can fit a cathedral on the APS-C format using the right lens from the right distance. The closer the subject to the camera, the larger its image. Eventually the image is the same size as the subject. This is called life-size or 1:1. The repro scale states the relative sizes of image and subject, so a scale of 1:2 means each unit of dimension in the image, say, 1cm, covers twice that unit in the subject: 2cm. Therefore the image is half life-size. Sometimes the scale is given as a magnification, so 1:2 becomes 0.5x, although it is actually a reduction.

Macro and micro

All pictures taken at distances from infinity to 1:1 produce images smaller than life size. In optics they are thus termed micro (‘small’ in Greek).

Again, in optical terms, macro begins to apply when the image is larger than the subject. On the repro scale, 2:1 means the image of the subject is twice its size (2:1 or 2x magnification).

The macro region extends from 1:1 to about 10:1 or 10x magnification, and is termed macro photography.

Micrography vs microphotography

Achieving greater magnification needs the camera to photograph through a microscope, which is the realm of photo micrography. There is one other term to confuse the issue: microphotography. As we’ve seen, most exposures are of subjects imaged smaller than life-size so, strictly, they come under ‘microphotography’. Yet the term is used solely for the reduction of documents, drawings and similar material to a fraction of their original size.

Microphotography was used for archiving on microfilm, but its main use is in the photofabrication of printed circuits, large-scale integration and transistors. The special lenses, corrected for a narrow spectral brand, can give 1:2000-4000 reductions, which is 1 metre reduced to 0.5-0.25mm.

Macro lenses

In the strictest sense of the term, there are few true macro lenses on sale to photographers. Most are the special monofocal lenses that can focus to 1:1.

The one firm that correctly terms its 1:1 focusing lenses is Nikon with its Micro Nikkors.

Many zooms have the ‘macro’ designation but they do not focus to anywhere near life-size, or 1:1, but justify the claim by being able to focus to a shorter distance than would normally be expected for the focal length span.

Early closer focusing zoom lenses only did so at the maximum focal length, which simplified the corrections. The longer a zoom lens’s focal length, the further away is its minimum focus distance. This is because it becomes more difficult to maintain corrections.

Also, the increase in overall length of the lens extension or internal group movement brings unacceptable growth in size and weight. Repro scale and magnification always relate the image size to that of the subject. However, by enlarging the image, one can obtain a larger-than-life print.

Lens construction

1866 Rapid Rectilinear

Thomas Dallmeyer realised a symmetrical construction gave good curvilinear and spherical aberration corrections, hence his Rapid Rectilinear of 1866.

1920 Plasmat

Paul Rudolph’s 1920 Plasmat – the final evolution of the perfectly symmetrical design. His 1892 Protar was the first to use the new Jena glasses.

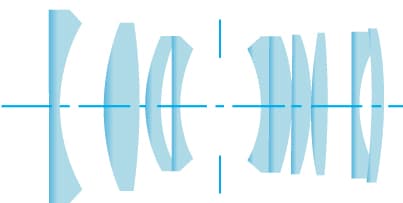

Modern 1:1 focusing lens

A modern 1:1 focusing lens. An SLR requires a retrofocus design, so the front group needs a broad front element to collect the light to pipe down the long barrel. However, its symmetrical design ancestry is visible.

Macro photography: the challenges

The difficulty of maintaining corrections with a ‘macro’ zoom lens in close-up invariably means that it is really only suitable for imaging natural subjects, so it is unsuitable for those with linear, straight-line features including document copying.

Even at more usual subject distances, as when imaging buildings, a zoom lens has to be of a high calibre if horizontals and verticals are not to look bowed. This error is termed curvilinear distortion.

If the lines curve inward to the frame centre it is popularly called ‘cushion’, and if outward it is called ‘barrel’ distortion.

When taking photographs of flowers, small creatures and so on with interest mainly in the frame centre, quite a measure of field bowing may be allowable.

Yet for accurate imaging and copying marked drawings, errors are unacceptable. That is why lenses designed specially for close-up work to a 1:1 repro scale are necessary.

Nikon may use the term rightly, but it has to be recognised that optical firms generally call this type of optic a ‘macro lens’. A top-quality 1:1 focusing lens will be a monofocal (of fixed focal length) optic and not a zoom lens.

The two main problems are curvilinear distortion (described above), and spherical aberration. The latter results in the image field being bowl shaped and not flat. It leads to an increasing loss of focus away from the image centre and with it a variation in magnification. It derives from the curved, spherical shape of the surfaces of the elements. It improves on stopping down, since a less deeply curved section of the lens components is being used.

Correcting spherical aberration

Spherical aberration can be corrected by moving one or more groups of elements in the lens as focused distance changes. Such a feature is often called a ‘floating’ element. Its incorporation in a zoom lens that already has moving groups is usually impractical.

The lower spherical aberration in zoom lenses nowadays is derived from the use of aspheric surfaced elements, those whose curves do not form part of a sphere. Their use has also made lower levels of curvilinear distortion possible in zoom lenses compared with earlier designs. Parallel progress in monofocal lenses has maintained the performance difference between the two in the best designs.

Image: Depth of field becomes very shallow as the subject gets closer and, as this shot of a dictionary page shows, even at f/11 it is limited to a few millimetres

Macro monofocals

A macro zoom lens may not work as close in or as well optically as a specially designed macro monofocal optic, but it does extend the choice of subjects in a worthwhile way.

We are all cost conscious and a zoom lens may be an economic necessity. If experiments with a macro zoom lens whet an appetite for more, it is time to look into the special macro monofocal lenses available.

Classically, close-focusing lenses have been based on a symmetrical design. This means that the rear group of elements behind the aperture diaphragm are identical to the one in front of it, only reversed or turned round.

In this way the residual errors in the front group are cancelled out by the opposite sign of the rear group. The effect is most efficient when imaging at 1:1 and decreases as focus distance increases.

Also, it does not work so well with wide apertures, which is why most early close-focusing lenses were of f/3.5-4 aperture. These are still found, though f/2.8 is the more normal maximum. Simple, straight symmetry has been extensively elaborated with modern optical technology to provide top-grade corrections, especially in colour, together with the wider aperture.

In the second part of his article, Geoffrey Crawley be looking at the special equipment available for close-up work and how it is used.