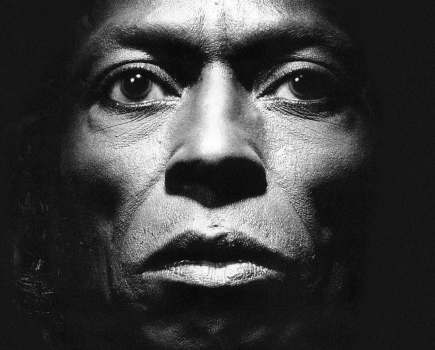

Robert’s image of a white helleborine. Nikon D300S, Nikon 200mm Micro, 0.8sec at f/4, ISO 200, beanbag, cable release, mirror lock

I have always enjoyed photographing plants, and although I very much consider myself to be a ‘generalist’ (in terms of nature photography) I have always had a soft spot for plants and fungi. Photographing flowers requires a very different mindset to shooting wildlife. In the case of wildlife, you need to be on your guard and prepared for the unexpected, whereas with flowers I find a more contemplative and slow approach is required. With wildlife, you are often dealing with what is in front of you at that moment in time with little control over where or when it will appear. With flower photography, on the other hand, you can experiment with viewpoints, lens selection and differential focus. You can take as much time as you want and even return another day in more favourable conditions. In short, you have unlimited creative possibilities which, in part, is what I so enjoy about this area of photography.

Like so many of us, I am forever striving to attempt different techniques in the hope of producing something fresh and original, to draw the viewer in and look more closely as opposed to merely moving from one image to another. It really is a difficult task in these days of social media, where so much outstanding imagery is posted daily.

However, in the spring of 2014, while photographing wood anemones, I happened upon a method of photographing these small delicate flowers in a way that I had rarely seen before. The sun had long since set and the sky was turning a deep inky blue, and there, as I walked along the path, was an anemone at eye level, growing on a fallen tree stump silhouetted against the twilight sky. I spent the next 30 minutes or so attempting to record this, and the resulting image spurred me on to investigate the technique further. I was excited. There were so many possibilities and, furthermore, from what I could see, few images had been created during this hour so I would be producing something different from the norm. Also, as it wasn’t weather dependent and my local woods lay just a ten-minute journey away, even if I’d spent the day at home processing images I could still pop out for a couple of hours, thereby ensuring I remained productive.

The perfect time

Twilight or the ‘blue hour’ is defined as being the period between daybreak and sunrise, and between sunset and night. To be more exact, when the sun falls below 18° you enter nightfall and when the sun rises to 18° above the horizon you enter daybreak or dawn. How long this lasts depends on your location and climatic conditions. In general, though, it does so for approximately 1 hour. My quest for photographing flowers at twilight would be confined to the evening, as from a practical standpoint it made much more sense than struggling to locate a suitable subject pre-dawn. My aim, therefore, for about a month, was to photograph plants during this period. My aim turned into an obsession, and as spring rolled into summer I would head out an hour before sunset to seek out an image and begin shooting as the sun slipped below the horizon. Often I would go out with a specific photograph in mind, but mostly I would simply see what I could find. I soon learned that no matter how interesting an image looked through the viewfinder as sunset approached, its appearance would change, rapidly, as the light faded. Warm tones would turn blue, the flower’s intricate details would slowly disappear and gaps through trees would emerge revealing an aperture in which to place the subject’s silhouette.

The white helleborine has a most graceful silhouette and would, I thought, be the perfect subject for this kind of photography. So, one spring afternoon, 14 months on from when I first started this project, I found myself visiting a local nature reserve where I had photographed them previously. The plants were in pristine condition, and with that evening’s forecast looking favourable (clear sky and still) I arrived with time to seek out and work on a suitable specimen. As I crawled around on all fours, with knees pricked by thistles, I began my search, but no matter how hard I looked I couldn’t, for the life of me, ‘see’ the image. I persevered and as sunset turned to twilight, a gap in the distant trees emerged and there it was – a perfectly formed helleborine dropped into place. The obsession continues…

Favourite kit

Lens of choice – the 200mm f/4 AF Micro Nikkor lens

Robert Canis

Robert Canis is a professional nature photographer living in Kent, England. He is represented by three international agencies and has been the recipient of numerous awards in such competitions as the Wildlife Photographer of the Year, Bird Photographer of the Year and British Wildlife Photography Awards. See more at www.robertcanis.com

For all my twilight images I used either the 105mm or 200mm Micro lens. Working distance and the relationship between the flower and background dictated focal length.

On this occasion I opted for the 200mm lens, which provided a good working distance and, importantly, kept me a safe distance from other plants. Due to the extremely low perspective, the camera had to be placed on a beanbag. I don’t like to lie down in such environments, which would normally be necessary here, in order to look through the viewfinder. I’m constantly aware of the impact I might make on the immediate area and flattened vegetation is something I wince at. How many of us, for example, have seen just this in bluebell woods? Because of this (and to avoid a cricked neck) I employed the use of a right-angle viewing attachment as well as a small torch to aid focusing. I activated live view, zoomed in to the flower and focused manually. When the wind dropped, I then switched off the torch and fired the shutter.