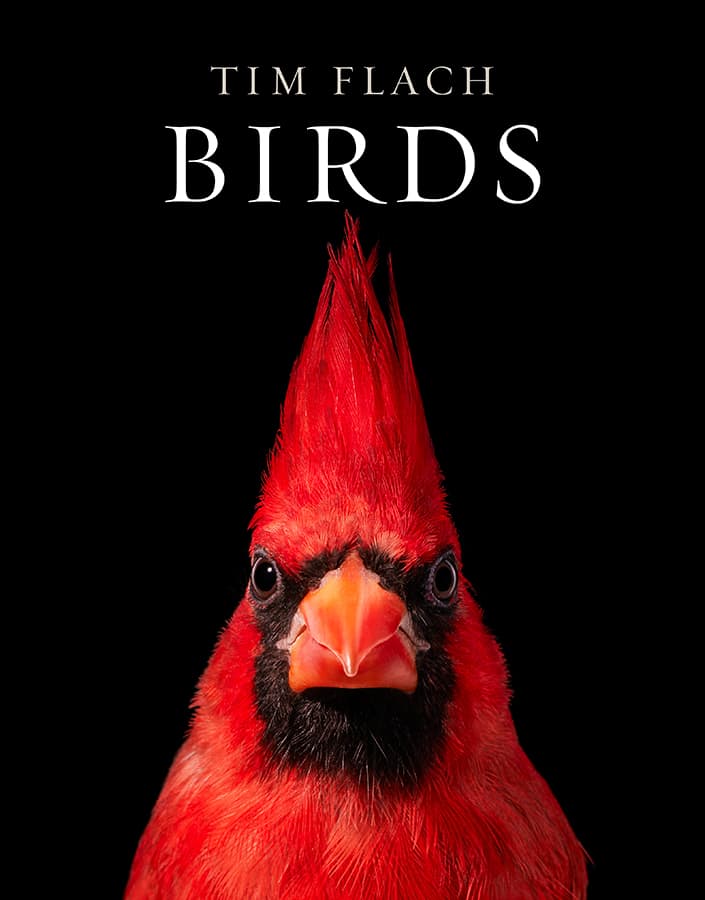

Tim Flach’s new book project celebrates the beauty and wonder of birds. He tells Amy Davies all about his latest masterpiece

The work of very few photographers has such a unique aesthetic as to be instantly recognisable, but Tim Flach is one such creator. Well-known for his ecological slant on fine art animal portraiture, his latest work, Birds, takes a look across the avian universe – from the common to the rare – in what he describes as a ‘slightly indulgent’ project.

Long an admirer of his work, the distinctive style of which puts it almost in a different category from most wildlife photography, it was a real pleasure to catch up with the photographer via Zoom earlier this year – just as he was preparing for the release of the Birds book, and gearing up for an exhibition in London which begins in December.

Tim’s previous project, Endangered, shone a spotlight on animals threatened with extinction. Although any project featuring animals is inextricably linked with such a plight, Birds was mainly shot with a desire to capture Tim’s love for magnificent, beautiful, and sometimes downright odd creatures.

As he explains, ‘You can’t remove yourself from the conservation message entirely, but having said that, this wasn’t the primary focus here. A book is a bit like a journey of discovery, you start not knowing very much about a subject, and you end it knowing just a little bit more. You meet amazing people who bring you into their respective passions for it, too.’

Gentoo penguins (Pygoscelis papua), found in the Southern Ocean. The gentoo penguin has been recorded swimming at more than 22mph, the fastest of any swimming bird

Created over a span of about three years, Birds has naturally been impacted by the effects of the pandemic. Much of the project had already been shot – principally the studio work – when the first lockdown was announced. The next stage of the project was supposed to be the animals that by their nature demanded that the photographer and his team travelled to them – so that had to wait a little while.

Throw Brexit into the mix, and the project wasn’t without its logistical challenges. ‘I was able to move through Europe fairly easily before Brexit, so I could go and collect some things in Germany and Holland, but the pandemic meant that certain key collections in Panama, Vietnam and America I had to give up on,’ Tim says.

‘There were some opportunities that simply changed however; for example, I was originally going to photograph puffins in Germany, but in the end it was easier to go to Skomer Island, just off the coast of Wales.’ There were some unexpected upsides to the sudden pause to life we all experienced.

Tim already had a working relationship with the curator at Sea Life London Aquarium, and the fact there were no members of the public visiting the attraction meant that Tim was able to photograph the Gentoo penguins in a way that simply wouldn’t have been possible under normal circumstances.

It also gave him the opportunity to re-examine not only his own work, but to have the time to find inspiration from elsewhere in the art world, which he has reflected in Birds.

‘With a simplified diary during lockdown, with fewer commissions and no conferences, I was able to re-examine some of the old masters of painting, and start to glean a little understanding of how they build up tones and so on – I was able to invest a little bit more in my own process, becoming more mindful of the importance of chiaroscuro and luminescence.

Of course, I couldn’t take as many photographs, so there were pros and cons [to the lockdown].’ It’s something you can really see in the resulting images in Tim’s book, perhaps more so than you might have noticed in previous works such as Endangered and Dogs. Tim says it’s also inevitable that any bird photographer is inspired by the great bird illustrators of the Victorian era, like Elizabeth Gould, John James Audubon and Edward Lear among others.

‘I don’t think you can go to a subject like birds and not think of them. But of course, there are things that photographs do better than illustrations – such as details, movement shots and reflections on water. Those are things that are problematic to do as an illustrator so I tend to go in those directions.’

Selecting ‘characters’ for the book and the project is by no means an easy task when you’ve got a choice of many thousands, and you also want to create a compelling page-turner. ‘There are at least 10,000 different types of birds out there, and I’ve got a 300-page book, so that’s about 160 different characters.

I also want the pace of the book to keep moving along and explore different things. There were also the so-called “must-haves”, like if I didn’t give somebody a bird of prey, a penguin, or I don’t know, a flamingo, they might feel cheated – a book on birds and they didn’t get the iconic ones. I did the ones that I feel you’d expect, but also the ones that are surprising, or are extraordinary characters.

‘I’m like a visual journalist in the way I go out, I look for a story and I try to distil what the key points are. With birds I wanted to look at what is the morphology of birds. When I arranged the book, I did it in clusters, which represented what was believed to be the evolutionary development of birds – known as phylogenetics.

I started off with a fossil, which was important to the understanding that really birds are like living dinosaurs. Then you go to the flightless birds; the birds that are specialists; and then eventually you get to the ones where we’ve started shaping them for our own needs.

What I wanted to demonstrate was that development of evolution – but in a loose sense because you can’t be absolutely definitive that they have evolved to this stage, but you can cluster them. Doing that allowed for the reference of the different jobs that birds do and how evolution has adapted.’

The project in its entirety may have taken a number of years, but for each individual bird portrait, the process can be as quick as a few seconds, or it can take multiple visits to a location to get a single shot that Tim is happy (or as close to happy as possible) with. ‘There is a bird called the Tragopan, which is a galliform (a ground fowl, like a pheasant).

It has a wattle that comes down and presents like a bib, but it’s unusual for it to display that in captivity. I had to make five different visits to Norfolk to get one shot. Others are realised in super-quick time – for example, the stellar chick: my producer placed it in position on a surface, and I had about one minute before it had to go back in the incubator.

Then we had hummingbirds, which because they’re moving faster than you can pre-focus might take thousands of shots before I get the one I want.’

Many of the images in this series were shot in the controlled environment of the studio. But Tim would argue that even images captured in the wild have some element of ‘management’ to them. ‘It’s the degree of which the mythology is perpetuated,’ he says.

‘Sometimes when you’re trying to deal with a bird that is in an aviary that is some distance away and doesn’t have too much human contact it can be more challenging than tracking down a lion in Masaai Mara which is photographed by tourists every day.’

As well as set-up studio shots, there were many shots created in aviaries, some of which were purpose-built for the project. But as Tim explains, even in those situations, the level of control isn’t as precise as you might think.

‘Some of the birds I didn’t have an ability to influence them, I just had to wait for things to unfold. In the studio I have perches where I could predict where they would go, and I had turntables so I could rotate them to the right angle. You could of course argue that’s a lot of control, but in the same way you could be in the wild and throw some meat down and wait for a lion to come into shot.

‘Birds don’t respond like a dog to a piece of cheese being waved either. Occasionally we’d try some mating call for a bird of paradise and it would puff itself up, but generally you’re quite restricted using sounds with birds.

I specifically built aviaries with the view of keeping the pressure off the birds, not wanting to stress them with the camera and the lights. A lot of this comes from having experienced people within your team – my producer, Daniel Cullen, has spent his whole life managing birds.’

In terms of Tim’s camera equipment, you might expect him to be using something highly specialised, but for most of the work he used a Canon EOS 5DS – its 50.6-million-pixel resolution being ideal for the kind of highly detailed imagery that avian work demands.

A few were shot on a Hasselblad, while towards the end of the project he switched to using the Canon EOS R5, a mirrorless camera, which gave him the benefit of Canon’s extraordinarily powerful Animal Eye AF capability.

‘For a lot of birds I was photographing with an 800mm lens and kind of hiding behind something or within a specialised aviary, where the bird can see more of the camera, just to get those very close-up portraits looking straight at the camera.

I wanted them to have that personality and character.’ As for lighting, although there is some studio lighting used, Tim says he prefers those which have been captured using natural sources.

It’s abundantly clear from chatting to Tim that when he decides to do a project, he dives in deep and becomes incredibly enthusiastic about the subject. Not only has he become knowledgeable about birds, he’s also realised an alignment between them and us as humans.

‘One thought about birds is that although dogs for example look at us and can read us very well, they are basically smell-orientated, and birds of course are sight and sound – which you could argue is a bit more parallel with us.’

It’s this human-like aspect that Tim feels is important to create a connection with animals – something which is especially vital when talking about conservation issues. ‘By choosing plain backgrounds, I’m not trying to focus on the context, or the landscape. I’m trying to bring it back to characters and personality, that draw us into thinking about them and their situation.

Inca tern (Larosterna inca), found in Chile and Peru. The handlebar moustache is an advertisement of good health

I think photographers have a role in a sense to be interpreters of popular science, they become like spokespeople. We’re at a time where it’s never been more important to connect with nature, and that ultimately we know our future depends on that.

‘At the moment I’m working with social scientists, I’ve co-published some papers that look at how the depiction of animals can lead to conservation. I think if we understand better what creates pro-environmental outcomes, then it gives us a sporting chance to get the right messaging out there to touch the minds and hearts of people.

A lot of evidence shows, in the papers that we’ve done, that if you bring that sense of otherness into our world, it grabs attention. That’s not to say that traditional wildlife or nature photography doesn’t have a very important place as an educator of the broader issues, but unless you can connect the viewer quickly, you’ve kind of lost them.

‘One of the great challenges isn’t always getting the people who are the believers, the ones who tick the boxes and say isn’t it outrageous that polar bears are feeding in the dustbins or whatever; it’s about getting the egotists. I’ve chosen to photograph [the birds] on backgrounds that aren’t distracted by the sort of natural habitat and that is really because a lot of romanticised animal imagery is in a non-human distant world.

Gaze is quite important, and it’s not by chance that the birds are looking straight at you. I’m using anthropomorphism because it can be used as a vehicle to initiate pro-environmental outcomes.’

On that vein, Tim’s next project (not due for completion for a long while) is going to focus on insects, which will essentially look at the bigger debates surrounding environmental problems and issues.

He says, ‘Having photographed a number of projects where I’ve met extraordinary people who’ve shared their special understanding of what’s changing and what’s happening, and also being a witness to that – particularly with my book Endangered – you can’t really unsee what you’ve seen.’

Tim’s fantastic new book Birds is available to buy now, published by Abrams. An accompanying exhibition runs from 8-24 December at Osborne Samuel Gallery, Dering Street, London. See timflach.com for more information.

Further reading

Tim Flach’s new book documents weird and wonderful endangered species