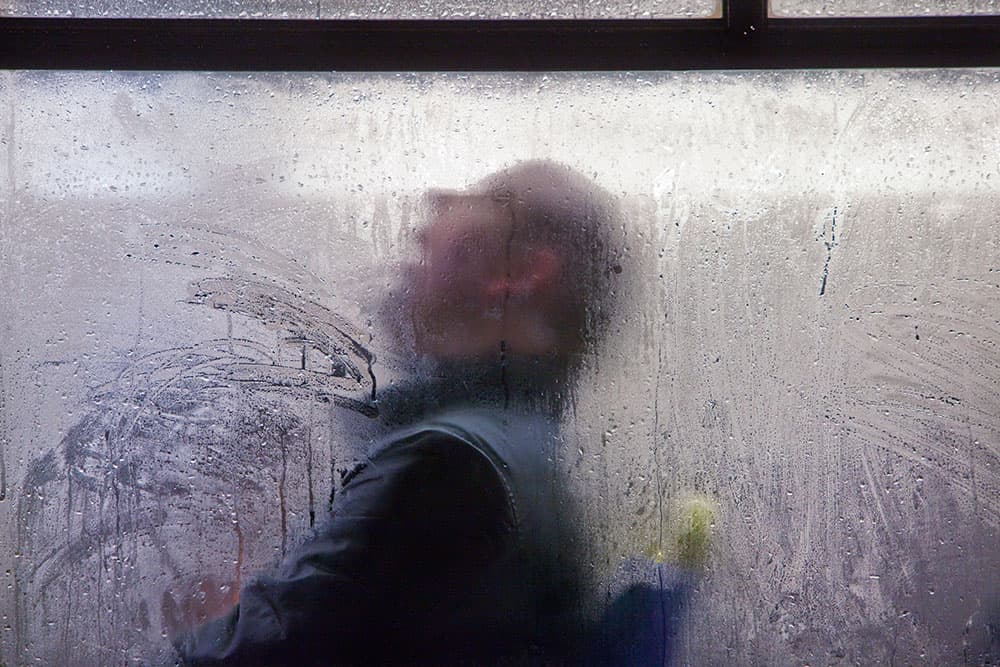

The combination of interior heat, exterior cold and condensation gives these images their unique abstract and dreamlike quality. Canon EOS 5D Mark II, 70-200mm, 1/30sec at f/2.8, ISO 800

Around three years ago, I was sitting in a café in East Dulwich in southeast London waiting for a friend. It was winter. As I was looking out of the window, I noticed the commuter buses ferrying passengers from the City of London and dropping them off around areas such as Dulwich and Forest Hill. It was a cold, wet night and I quickly noticed how beautiful this observed mundane scene was through the window of the café.

Every time a bus pulled in, it was like a survey or study of the types of people who commute every evening on London’s buses. On just one bus, you’d see all ages and classes sitting together, ranging from businessmen and students to the elderly. It was extraordinary to me and I knew there had to be a device or project here that could form a series of portraits of Londoners. It’s been three winters since that revelation, and the result is a book called On the Night Bus, published by Hoxton Mini Press.

When I decided to embark on this project, the hard part was finding the right location in which to shoot. The key that ended up unlocking the project was finding a spot in Elephant and Castle [south London] outside the big shopping centre. There’s a raised area there and when you come out you find yourself at a first-floor level. That location is a particularly busy bus junction, so buses were constantly pulling up in front of me. It’s an area that I’ve passed through many times on my way to meetings and jobs in south London, so it’s a place I know fairly well. When I scouted it out one evening, I knew it was the perfect spot. It was finding that location that got the project going.

Here we see how important the artificial light of the bus interiors is in each image. The blue cast of this shot is almost reminiscent of Picasso’s ‘blue period’. Canon EOS 5D Mark III, 300mm, 1/60sec at f/4, ISO 200

Getting technical

Technically, it took me a few weeks to get my head around the best way to approach the idea. I tried a variety of different formats and lenses. Right from the off, I knew it had to be ambient light and shot at night. The circumstances were quite difficult to work in when factoring in the technicalities of the exposure and the weather. Generally, it was very cold and wet.

The buses would pull in and I’d have a window of around 60 seconds in which to shoot. In that time I had to weigh up the people in each of the 12 windows on the top deck and choose the best subject. I was always looking for particular things, such as a woman in a headscarf who could look almost like a Madonna figure. Or sometimes there would be a strong blue cast in the interior of the bus. Every bus had different artificial lighting or a slightly different interior.

Eventually I reached the point where it was quite easy to get nice shots, even though I was shooting handheld at around 1/40sec and using either a 300mm f/4.5 lens or a 70-200mm f/2.8 lens on a Canon EOD 5D Mark II and then later a Canon EOS 5D Mark III. I used those cameras because they have fantastic low-light performance.

They’re also the cameras I use for the majority of my commercial work, such as the work I do for Transport for London. I have a contract with them that means I spend a lot of time in tunnels and dark environments. The image-stabilisation lenses made the project possible. Without them, I couldn’t have shot using such low shutter speeds.

I had to be mobile, so I couldn’t use a tripod or monopod. It was necessary for me to walk up and down the length of the bus quickly and shoot. Sometimes I would check out one bus and then another bus would pull up right behind it, meaning I had 24 windows to contend with. While the images themselves are quite discreet, the process of making them was incredibly frenzied.

On top of that, I had just a two-hour window in which to work – between 5.30 and 7.30pm. That’s London’s rush hour. The buses were always crammed with people, which meant lots of breathing and condensation, plus cold exteriors versus warm interiors – a combination that made for great images.

This is one of Nick’s favourite images from the series. It’s one that suggests a narrative that can lead the viewer down all sorts of paths. Canon EOS 5D Mark II, 70-200mm, 1/40sec at f/3.5, ISO 1600

Working with variables

What was particularly helpful when building this project was constraining some of the variables. With a project, you can emphasise some parts and other parts you can leave open. The people themselves were the variables. The buses and weather were always the same, as was my technical approach. But the people – what they were wearing, what they were doing – were always different. The basic key to street photography was still there, although it’s debatable whether this was a street-photography project.

I generally think that street photographers shoot single images that stand alone, rather than something long-form like this. At the same time, On the Night Bus still features candid photography shot in a public place. It’s a very close relative to the genre. I’ve been shooting those kinds of single candid images for several years and what I’ve been doing these last few years is trying to make candid images that look different from the standard vocabulary of street photography. In those instances I was using a small camera, such as a rangefinder, with a little 35mm lens. There’s a similar vision present here, in that the things you see and observe change all the time.

As Nick suggests, the project illustrates a cross-section of London’s nightly commuters, ranging from rich to poor and old to young. Canon EOS 5D Mark II, 70-200mm, 1/40sec at f/3.5, ISO 1600

Editing down

In the early pictures, I included parts of the bus, such as parts of the window or exit signs. I showed my early pictures to some people, one of whom was the former picture editor of The Observer. He really encouraged me and suggested that the ones without context, were much stronger in their abstract feel.

In the end there were around 4,000 raw files. I edited them down to something like 109 images and the book features just over 50. The editing was done digitally. I have two huge Apple cinema displays on my desk and I would load all of the thumbnails up to look on those. It was something I could do in bite-size chunks.

Every day, I would come back, download everything, back it all up and then edit. I used a little software package that nearly all press photographers use called Photo Mechanic. It allows you to see and edit your images extremely quickly.

I then used an Epson printer to produce 6x4in prints of the images that I liked. I printed perhaps a couple of hundred and then set them out on my dining-room table. I looked at the entire body of images to see if there was anything I felt was missing.

Sometimes I would see three contenders for a front cover or another three that would echo one another. Working in that way meant the project could develop organically. It was quite an old-fashioned method of working, as it was done with small prints, but I really enjoyed it.

On the Night Bus is a completely personal project. That was one of the nice things about it, being a commercial photographer. I didn’t have to rush it and could work on it when I felt ready.

When Hoxton Mini Press offered to publish the book, I felt it was almost ready. I shot for one more winter and then handed it over to them. It’s virtually sold out now and the publisher is having to reprint it. It really seems to have resonated with people.

This is a great example of a happy accident. The smears almost appear to be gushing from the subject’s throat. Canon EOS 5D Mark II, 70-200mm, 1/40sec at f/5.6, ISO 1600

Nick Turpin was born in London in 1969. In 1990, he worked as a staff photographer with The Independent and then pursued a second career in advertising and design photography. In 2000 Nick was the founder of the international street photographers’ group iN-PUBLiC and in 2010 he established Nick Turpin Publishing. He has also taught and lectured on contemporary street photography at museums, universities and on TV. See more at www.nickturpin.com. On the Night Bus is published by Hoxton Mini Press, priced at £16.95.