The popular science and travel writer Bill Bryson once observed that if one were to imagine the entire history of the Earth compressed into a single day, humans would not show up until one minute and seventeen seconds before midnight. The entirety of our recorded history would comprise just the last few seconds. Individual lifetimes, barely an instant. We are, by all accounts, a very short-term and temporary feature of this planet.

Perhaps this goes some way towards explaining our fascination with mountains. While in the grand scheme of things they are no more permanent than we are, to a short-lived species like us they certainly seem it, and for as long as we’ve understood that mountains have peaks, we’ve had the urge to scale them, conquer them, and understand them. Lots of us have died in the attempt.

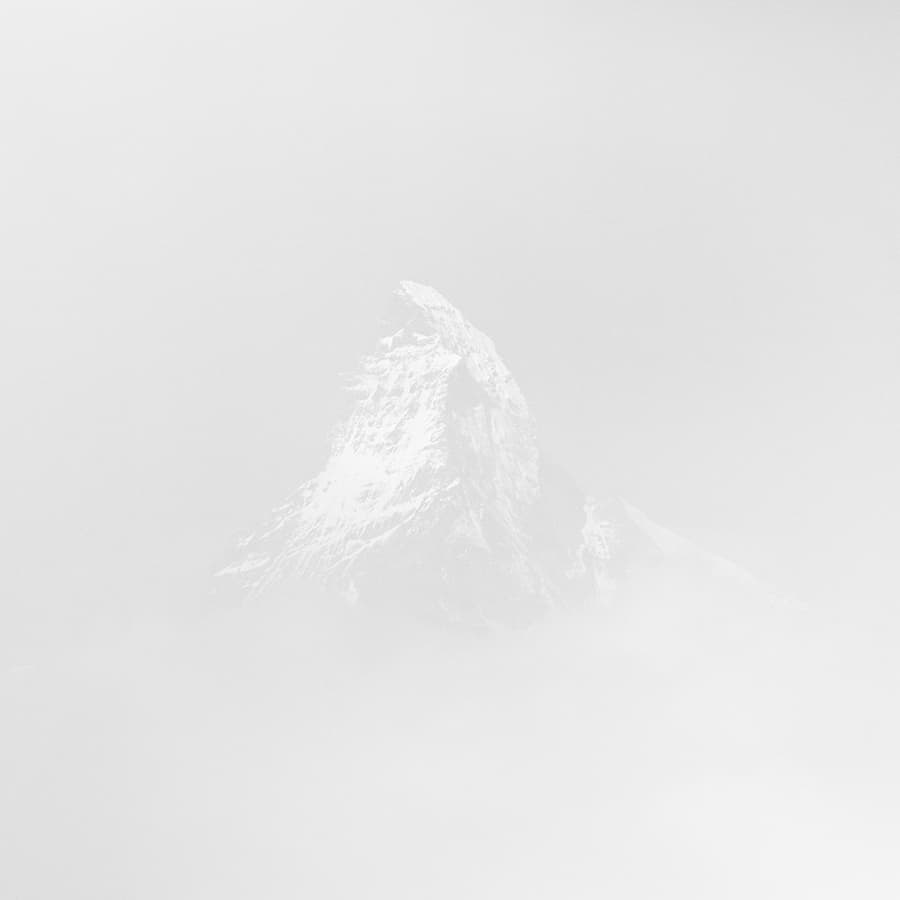

The Matterhorn is one of history’s most intimidating peaks, and for this reason was among the last of the Alpine mountains to be successfully scaled. In his new book Matterhorn: Portrait of a Mountain, photographer Nenad Saljic captures a flavour of that indomitable “otherness” that makes the mountain such a fearsomely beautiful thing. At all times, in all conditions, that distinctive craggy shape remains, indomitable, supremely unruffled by the regular presence of brave or foolhardy humans who seek to climb it.

It’s a fantastic book, and we couldn’t resist getting in touch with Nenad to find out a little more about it. Scroll down to read our short interview and see more images from the book…

Amateur Photographer: So first of all, why the Matterhorn? What inspired you about this mountain above all others?

Nenad Saljic: There are several aspects about the Matterhorn that have attracted me. Artistically it is one of the world’s most magnificent mountains; with a pyramidal shape, and standing quite alone, it could be considered an ideal mountain. It is so special that even other similar mountains elsewhere are called by the same name.

The special atmospheric conditions suitable for banner cloud formation are found in the lee of isolated mountains when sufficiently moist air flows across especially sharp mountain peaks like the Matterhorn.

Historically the Matterhorn had long been deemed inaccessible, and it remained unclimbed after most of the other great Alpine peaks were reached. The first ascent by Edward Whymper and party exactly 150 years ago marked the end of the golden age of alpinism.

The Matterhorn is a geological phenomenon. It was born from the remnants of an enormous African rock mass that originated more than 250 million years ago. This mass was pushed northwards colliding with the European continental plate, forcing its way upwards and resulting in alpine folding 90 million years ago. It reached its maximum height 20 million years ago, modeled by natural erosion from the top to the bottom, and finally acquired its characteristic pyramidal shape over the last 2.6 million years.

What makes it even more interesting is that the usual rock sequence has been reversed. The last thousand meters towards the summit is composed of the fragments of the old African plate, lying on top of a younger base composed of the rocks from the ocean floor almost half that age.

AP: You’ve been a mountain photographer for some years now I believe – what first attracted you to mountains as subjects? What challenges do they present?

NS: I’m not only a mountain photographer but I’m trained as a mountaineer and caver in my youth, so my first art projects were connected with the mountains, especially with caving photography. After hiatus of 18 years I’ve just returned where I stopped long time ago.

AP: Your portraits of the Matterhorn in the book are always taken from a distance – we never get too close to this incredible behemoth. What was the reasoning behind this decision?

NS: A lot of people ask me a similar question. There is a Buddhist saying that the best view of a mountain is not from the top, because once you are on the summit you cannot see the mountain itself. This is a nice philosophical excuse, at least.

AP: To me the images seem to explore themes of transience and permanence – the Matterhorn remains constant in your images while fleeting light and weather patterns swirl around it. And yet, as you observe in your text on the project, it too will one day disappear. What are your thoughts on this in relation to the project?

NS: When I learned something about Matterhorn geology I started to appreciate it even more and to look at the landscape with different eyes. It opened deeper thoughts and perspective in the project.

Matterhorn: Portrait of a Mountain by Nenad Šaljić is available now, priced £65/€92/$102. Visit nenadsaljic.com