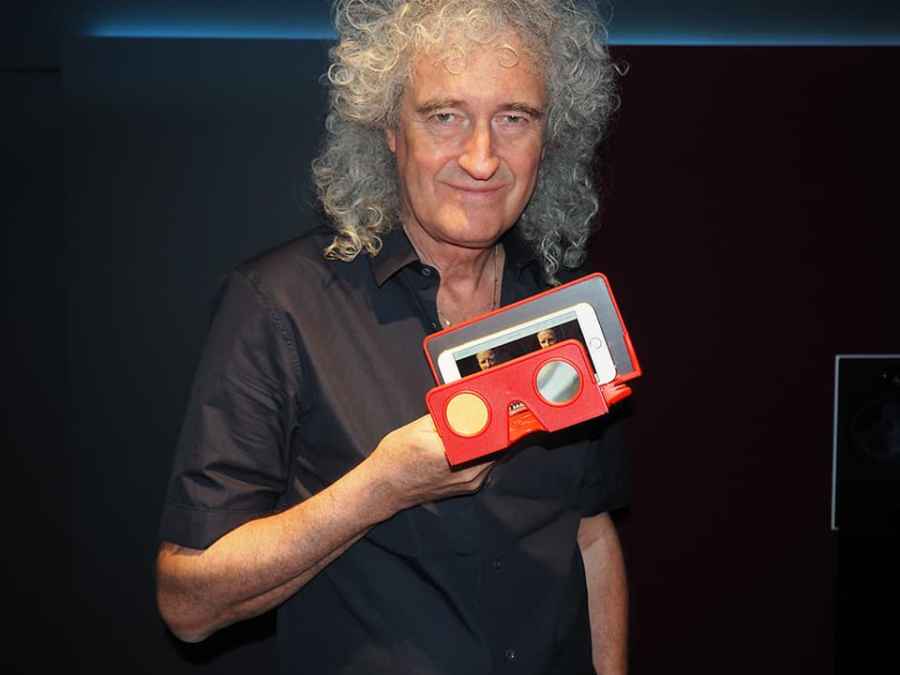

Brian May with his new OWL viewer – housing a smartphone displaying stereo images he took of APs news editor Chris Cheesman – [© C Cheesman]

He may be weary from the travelling, but May’s passion for what Victorians called stereoscopy – ‘virtual reality’, in 21st century jargon – remains undimmed.

This lifelong expert and fan of the third dimension began collecting stereo cards given away free with packets of Weetabix cereal as a boy. He now has 100,000 of the things.

Ever keen to expound on all things 3D, interviews with journalists to promote his new stereo-viewing device are running behind – so late, in fact, that his PR entourage are told to vacate the screening room set aside for ‘one-on-one’ interviews. Their time is up.

Amateur Photographer’s scheduled interview time came and went an hour ago and it appears we have been defeated by the cleaners. Are we about to be shown the door? After all, May has been talking 3D for more than four hours and does have a plane to catch.

We needn’t have worried. An upstairs meeting room comes to the rescue and, installed safely inside, May is relaxed and clearly relieved as he takes a seat and hears this is his last interview of the day.

‘Hooray,’ he cries as if he’s just come off stage on the final date of a tour after a long night of encores.

How do you find time for all this 3D stuff – is it your way of switching off?

‘I don’t know what it is. I seem to be kind of driven. And I’m so fortunate that I get to do all the things that I dreamed of doing when I was a kid – stereoscopy, being a rock star, playing music, helping to give animals a voice, which I always dreamed of, and astronomy.

‘Maybe, I’m slightly nuts…’

He’s certainly as nuts as ever about 3D. ‘It’s the reality [of it]. It’s the absolute magic of feeling that you’re there in some place you couldn’t possibly be.

‘It’s like a time machine. You can find yourself back in a situation that you were in that you can recreate, or you could be creating a situation like you are in the international space station, or you could be diving with sharks.

‘And the more real you can make it, the more wonderful it is. It’s just enchanting.’

3D TV – what happened?

When we last spoke, in 2011, 3D was being touted to a potentially whole new global audience, through 3D TV. At the time, May admitted that the format was ‘perched on the brink’.

But 3D TV has failed to win over the masses, perhaps down to the need to wear those wretched 3D glasses. ‘I think it’s fairly well proven that people don’t like to sit riveted to one spot to watch their TV,’ May reflects. ‘They like to be watching their TV while they are cooking or putting their kids to bed or whatever they do.

‘So, no I don’t think TV has worked out at all.’

The movie industry’s flirtation with 3D has formed a more solid bond, although he reckons this may have peaked.

‘Film’s worked out pretty good, but I think there’s a slight backlash from the fact that a lot of the 3D films now are conversions, and the conversions are never perfect,’ May explains.

‘And sometimes people overdo it. Sometimes they underdo it and people get slightly jaded from it.’

Either way, he believes his new £25 viewing gadget stands a better chance of surviving the vagaries of the 3D phenomenon.

The collapsible device is a 21st century twist on one that Victorian enthusiasts first used to view stereo cards.

He sees 3D as now having gone full circle, returning to the days when Victorians first saw magic created before their eyes – a concept that gripped the world in the 1850s.

In May’s eyes, there is little difference between ‘stereoscopy’ in the 1850s, ‘3D’ in the 1950s and ‘VR’ in the 21st century. ‘The 360° [VR] thing is great, but basically you are looking at a stereoscope,’ he says.

Google joined the VR bandwagon in June 2014, and reportedly shipped more than five million of its low-cost fold-out cardboard viewers in the first 19 months. Like May’s new device – Google Cardboard allows the user to view smartphone images in 3D.

The new £25 OWL VR Smartphone Kit, due out next month

The new £25 OWL VR Smartphone Kit, due out next month

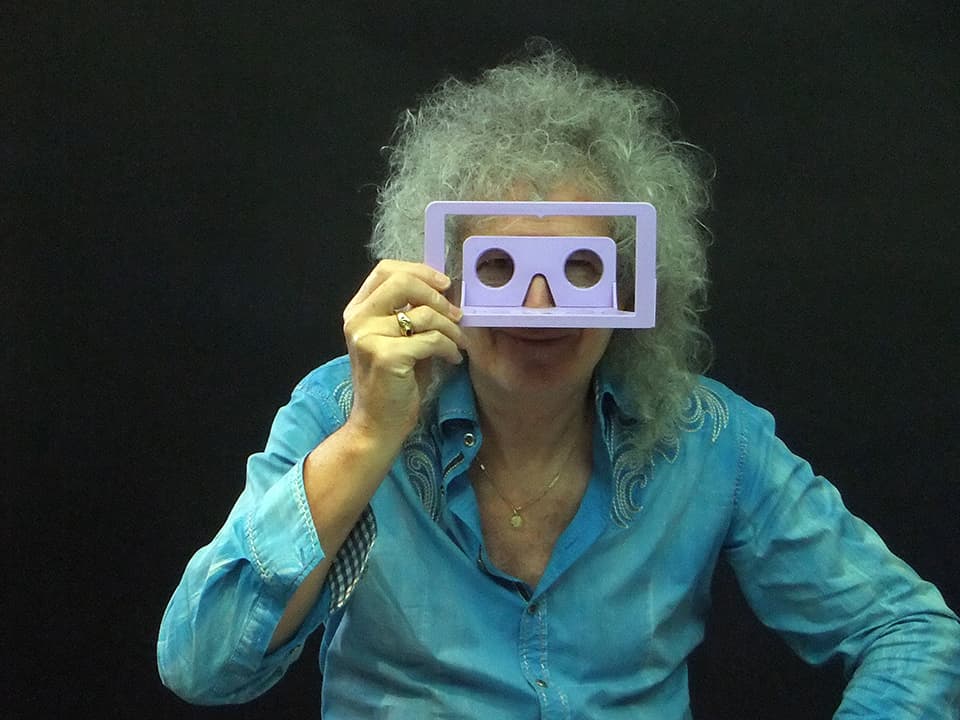

Journalists try out the device’s virtual reality potential at the Dolby offices in London [© Andy Westlake]

The musician-turned-inventor hopes to tap into a technology that has ‘taken the consumer electronics industry by storm’, as availability of VR content grows.

Schools plan

May predicts that the idea of taking the viewer into another world, through an ‘intimate experience’, is likely to take hold again, pointing out that stereo views ended up in every school around 1900.

Introducing the OWL to schools, through his London Stereoscopic Company, may be one way of boosting its mass appeal – and he plans to do just that.

‘I get great a response from kids with these things,’ he explains. ‘They all love ’em. And they love it even more when they realise they can take pictures of themselves and their mates in stereo and immediately see them.

‘It doesn’t look like education if you show them what it’s like to live in the Pyrenees or something.

‘You can just put them in a virtual reality place where they find out what it’s like to be an Eskimo. I think there are great possibilities… I’m talking quite young kids. Some of my grandchildren really enjoy this.’

Like the Google Cardboard, the appeal of May’s OWL Stereo Viewer may lie in its simplicity and cost. For one thing, you don’t need to wear uncomfortable 3D glasses.

And crucially, it is designed to fit any type of smartphone.

It enables the user to view images taken by the user that are converted for 3D viewing using existing downloadable apps, view existing 3D content already available online, and VR material such as films and concerts.

How does the OWL differ from other viewing devices on the market, such as Google Cardboard or the new Oculus Rift headset?

Unlike the Google Cardboard, the user can adjust the focusing to obtain the correct distance between the eyepieces and the stereo images. ‘The geometry is different. You need geometry that doesn’t give you headaches.

‘These are slightly longer focal-length lenses, which means you won’t see the dots on your camera screen, and that makes it slightly more comfortable.

‘There are a number of things about this that make it more comfortable – the fact that the lens separation is outstandingly wide, which is why it’s called an OWL, makes a difference too.’

The adjustable focusing may be key – especially for older users – but so is the ability to access a phone’s buttons when attached to the device, May asserts.

Also, the viewer is not in a box, ‘closed in’. But he doesn’t feel this affects the ‘immersive experience’.

‘Astronomers never close one eye to look into a telescope,’ he says. ‘They are aware of the world around them so they can be immersed in virtual reality without having to block everything out.

‘I find that most people who use these Oculus [Rift] things start to feel claustrophobic after about ten minutes and there’s pressure on their eyes because it’s strapped to their head.

‘This doesn’t strap to your head. It’s very light and easy to hold, and you can move it around and adapt it as you need. So, it’s a different kind of philosophy towards virtual reality.’

May says he launched his original OWL viewer, designed to view stereo images in books, ‘because there was no viewer available in the whole bloody universe except a few Victorian ones’.

But, halfway through designing the latest incarnation, he realised he could make it hold a stereo card. ‘Then we started thinking; the phone is everybody’s access to the universe these days… wouldn’t it be great if the phone could go into your OWL and access the stereoscopic universe. So, all it needed was some way of holding the phone.’

After wrestling with the idea for 14 months, and trying various clips and springs, a ‘fridge magnet’ provided the spark for a breakthrough. He designed the new OWL so a smartphone could be attached to a magnetic back plate, using a removable steel strip that sticks to the phone with adhesive strips.

The new OWL is built to hold a stereo card or a smartphone [© Andy Westlake]

My 3D selfie stick

For May, compatibility with any phone is a huge selling point, not that he needs to sell many with millions in the bank. Plus, you can still access the phone’s controls.

May just can’t leave 3D alone, it seems. Even on stage where he uses a 3D selfie stick during shows these days.

‘In the beginning I was just doing stills,’ he adds. ‘I started with a regular selfie stick and I thought, “Hmm, it’s got be stereo.” So, I got two GoPros and took stills of me and the audience – it can be 50,000 people, which is great.

‘And now it’s turned into a 3D movie… I do a panoramic sweep around, while the [audience] do a kind of Mexican wave or as they hold up their iPhones with the lights on. It’s amazing to see.’

‘Queen in 3D’

On and off-stage, May has captured thousands of images on tour with Queen, many of which may soon see the light of day. His friend and collaborator Denis Pellerin from the London Stereoscopic Company has been scanning all the 3D shots.

‘I always had a 3D camera with me, so, there are pictures of Queen on-stage and off-stage…

‘I just have to assemble all the words now to make it into a book. It’s a project I’d like to have off the ground next year: “Queen in 3D”.

‘I’ve also been accumulating a lot of fabulous astro stereos. I was fortunate to know a lot of these people who work in the field….

‘You can take stereo pictures of pretty much every object in the solar system these days. You can’t take them with your own camera, but you can find pictures from various probes and put them together. They’re real stereos, they are not manufactured, they will be the real thing.’

Reflecting on his vast archive of stereo cards, May said he wants to put the best online and release an app to showcase them. ‘I’ve been collecting these things for 40 years or whatever and it’s a real treasure trove…’

May has already uploaded pictures of skeletons from his series of French stereo cards from the 1860s called ‘Les Diableries’ via an app.

Next, he wants the online library to include images from his mission to track down stereoscopic cards created by Victorian photographer TR Williams from his ‘A Village Lost and Found’ project.

‘I’ve restored the cards,’ says May. ‘I’ve spent thousands of hours restoring them and now I can share them….’

May is casting his 3D net ever wider. He now writes soundtracks for 3D movies and this week filmed Queen’s performance in Barcelona in 360° VR.

‘Things cross-pollinate… It’s nice for me to be able to sit at the hub, at the junction of many different worlds,’ he says.

On stage or off, May’s head may be spinning for some time to come.