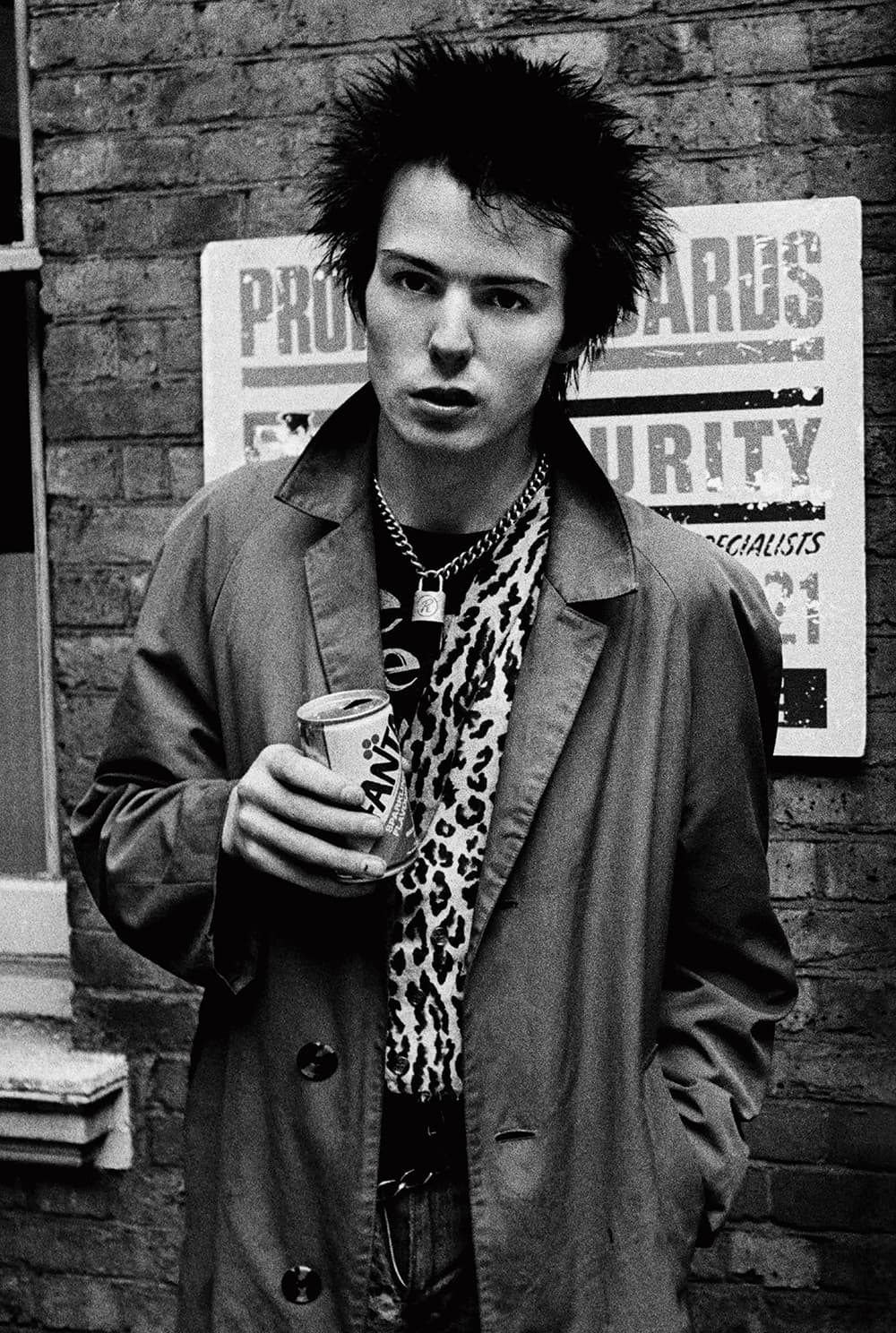

Sid Vicious, Sex Pistols Oxford Street Glitterbest photo session, 1977

In a seemingly bizarre career move, in the mid-1970s Adrian Boot swapped being a physics teacher for a life as a music photographer. At the root of this change was the fact that he was teaching in Jamaica and had already begun to document the reggae and Rastafarian culture of the island.

‘During that time I pursued my hobby as a photographer – mostly in black & white, and mostly people and street photography,’ says Adrian. ‘I wasn’t so much interested in palm trees, beaches and blue skies. It was much more the gritty, reportage, sort of “romantic side” of photography. I came back from Jamaica with a hoard of black & white snaps I’d taken over the years.

‘I used to take photographs, make the prints in my house in Jamaica and take them round the local community and give them away. It was quite rare to get hold of a photographic print of anything, so I became quite popular. That gave me a lot of inroads into what was going on, and I came back [to England] and published a book called Babylon on a Thin Wire, which was sort of the “underbelly” of Jamaica. Thames & Hudson published it and there was an exhibition based around the prints at The Photographers’ Gallery… but I thought that would be it.’

The book sold well. ‘A lot of the images in the book are pictures of Rastafarians and musicians,’ says Adrian. ‘Don’t forget that in 1972 nobody had ever heard of Rastafari or paid any notice at all to reggae or Jamaica.’ By this time, Adrian was back in the UK teaching but decided to take a sabbatical year to pursue photography, ‘…because people were calling me up all the time. I’m still on the same sabbatical – I never went back!’

Adrian’s ‘can-do’ approach certainly helped. ‘In those days it was about being able to get a dozen or so prints, and get them onto the editor’s desk the next morning,’ he says. ‘That’s not such a frightening prospect these days, but when you had to process a roll of 400 ASA film for a live concert, then struggle to get a print, it was quite a challenge. It was less about how good the photography was; it was more about, “Did you get a picture of so-and-so and where is it?”’

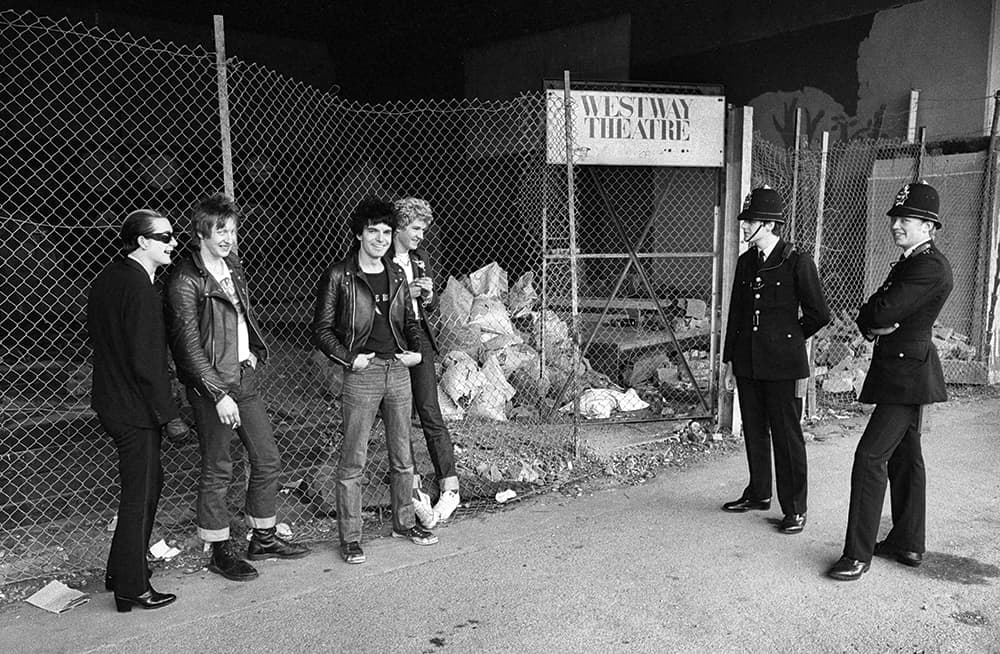

The Damned, Westway Session interrupted by police, London, 1975

The music papers

Adrian’s work began to be published regularly in the music papers, and in 1975 he became staff photographer for Melody Maker. ‘You could count the number of photographers who were covering the music scene on the fingers of one hand,’ he says. ‘We were all shooting in black & white because, of course, [laughs] colour hadn’t been invented yet… well as far as NME and Melody Maker were concerned. I was busy shooting every day. If it wasn’t a concert, it was an artist in a hotel room or I’d go out and try to get a photo of an artist who probably didn’t want his photograph taken.’

He continues: ‘Then punk came along and crossed over with reggae and the whole “Jamaica scene”. Basically, they all lived on the same council estate so the music crossed over and you got a lot of white kids going to reggae “shebeens” and vice versa. So, that’s how I kind of got involved in The Clash and the punk scene, as well as the reggae scene which was beginning to grow.’

Adrian hesitates to recognise punk as a ‘movement’ and explains: ‘It always strikes me as quite strange the way that, years later, people try to intellectualise these phenomena. At the time, punks were almost the dregs of society; people who couldn’t get jobs and were disenfranchised. Not much has changed – young people are still in the same state! The difference in those days was that you could still go to art school for free, mess around for three years and even form a band, which a lot of people did [laughs].

‘They didn’t care whether they were good enough to play music and the record companies weren’t that interested anyway. So, from that point of view, I guess punk was a bit of a cultural thing, but I certainly didn’t think it was anything special. It was a bunch of kids from the local council estate trying to form a band and doing their own magazines – lots of people were doing lots of different things.’

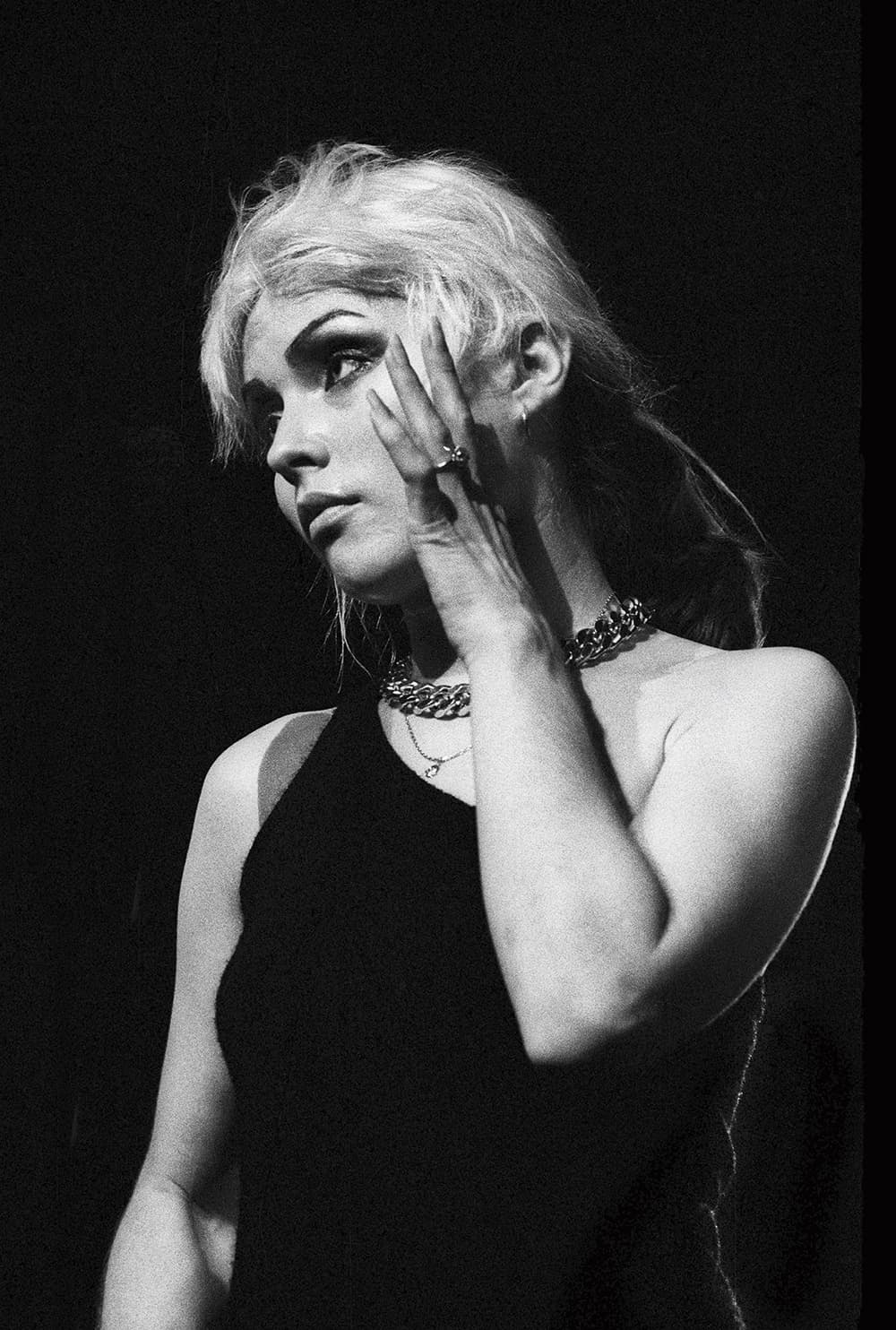

Debbie Harry of Blondie, live in London, 1979

Working with punk rockers

Adrian was at the heart of documenting the punk scene in the UK and the US, but did he find the bands difficult to work with? ‘Not really, no,’ he says. ‘The Clash were really easy – they were nice people and quite well educated; they were the “art-school crowd” I was talking about. With the Sex Pistols – well, John Lydon was an intelligent guy and he didn’t suffer fools. The others, well, you wouldn’t even try to have a conversation with Sid Vicious, but I only photographed the Sex Pistols two or three times.

‘I photographed The Clash lots of times; I was a lot closer to them. But did I like their music? Sort of – I liked The Clash but I wasn’t that keen on the Sex Pistols. I mean, their shows were always exciting – for me a band is great if they’re photogenic and there’s a lot going on on-stage. If it’s just a guy with a guitar standing there for an hour and a half I tend not to like it, even though the music might be amazing. If somebody’s jumping around the stage, causing mayhem with audiences erupting, then I’m on the case and the time is filled with that; I don’t get bored.’

Of the punk-era artists he worked with, Adrian has a few favourites. ‘I liked working with Debbie Harry [of Blondie] because she was so picturesque,’ he says. ‘It revolved around whether I was going to get a good picture; if I knew I was going to get a good picture, I enjoyed it.’

As for his camera kit at the time, Adrian recalls: ‘For concert work it would have been the trusty Nikon F-whatever and I always had a couple of lenses. I’d have a 200mm lens, a fixed one – in those days zooms weren’t that good – and I’d have a wideangle lens, maybe a 28mm; then a 90mm, like a portrait lens. I also had two Leica M4s and an array of lenses, but they were useless for live concert photography. In fact, they were useless for most things except street photography and reasonably close-up stuff; they did have a telephoto lens but it was a pile of junk. It was only relatively recently that I let my Leicas go.’

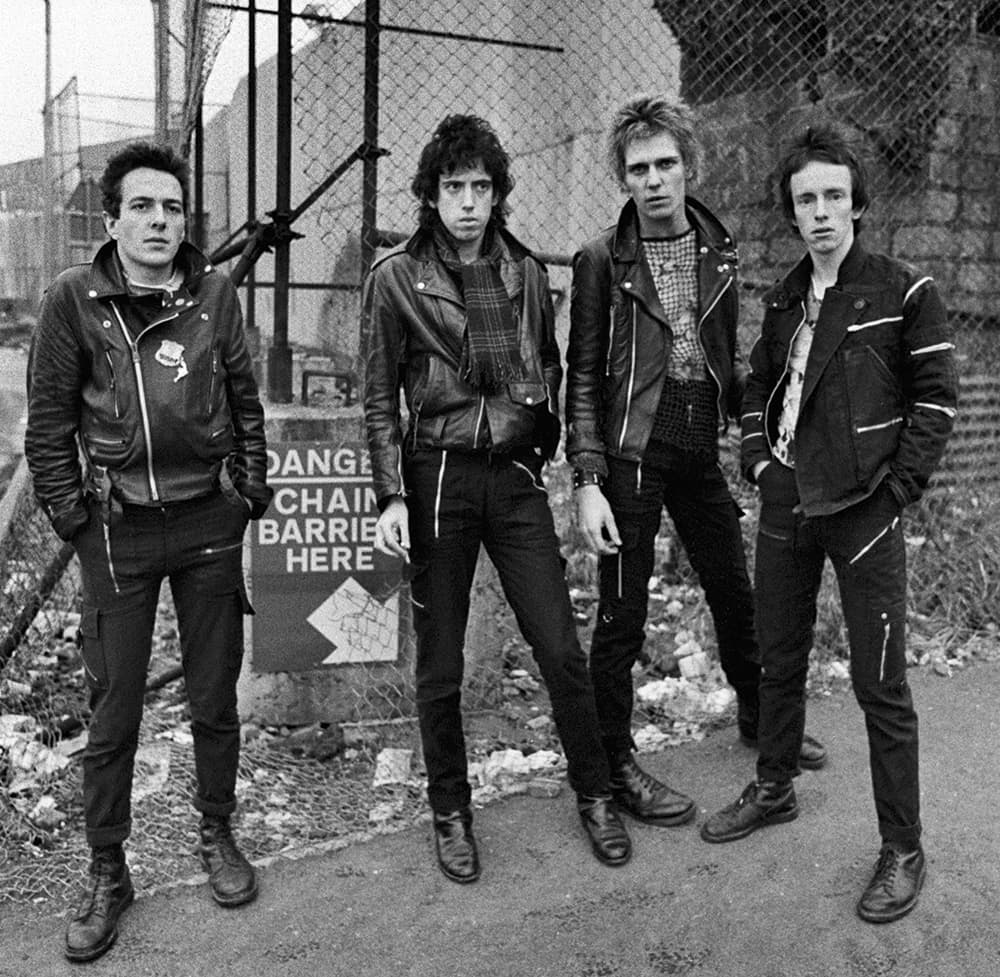

The Clash in Belfast, 1977

The Clash in Belfast

Arguably Adrian’s most famous punk photographs are of The Clash on the streets of Belfast in the midst of ‘the Troubles’ – a period when being an Englishman on the streets of the city was not viewed as a wise move. Adrian reveals: ‘The Clash was always good, particularly with things like Belfast where we got into quite a lot of trouble… but I liked all that; I liked pushing the boundaries a bit. So there we were in Belfast; advised not to leave the hotel, which is precisely what we did. We got into a taxi and went down the Falls Road… I got into such trouble with the record company, which asked: “What are you doing endangering the lives of our band?” But the pictures got the covers of all three music papers – Sounds, Melody Maker and NME – the following week. After which CBS thought I was the best thing since sliced bread.’

Adrian adds: ‘Technically, the pictures were rubbish. Because it was a very drizzly day, I pushed the 400 ASA Kodak Tri-X to 800 ASA, so it was a bit grainy. If they were entered into a photographic competition, to be judged on all the usual criteria, they would have been put in the dustbin. But because of the subject, and because no one else was able to get it as it was unique, it was successful. That’s often the case. Photography is not so much about cameras, film and the process; it’s about the interaction with people. It’s about having enough bottle to knock on the dressing-room door.’

A selection of Adrian’s iconic punk photographs is being exhibited at Proud Camden. ‘We could start poking into our archives and start pulling out unusual, never-been- seen-before [pictures] but for an exhibition like this I think people want to see the icons,’ says Adrian. ‘So it tends to be the pictures that have already made a name for themselves that are used.’

He adds: ‘I manage to make a living because, of course, Joe Strummer’s dead, so you’re never going to take another photograph of Joe Strummer. I guess if you’re a portrait or celebrity photographer, the secret is to outlive your subject.’

The Specials in concert in Brighton. A stage invasion brings the concert to a climax, 1981

Future projects

Adrian still shoots – including a recent project with singer Grace Jones – usually with his Nikon DSLR or personal pictures on his iPhone 6, which are often posted on his Facebook page. As for what’s next, he explains: ‘I’ll be spending my days going through the photographs that I’ve taken and putting those out. I’m in my element ploughing through old negatives. There are bands and stuff that have never been scanned in and never printed. I enjoy the research side and I enjoy looking back and using the work. I kind of knew when I was doing it that I wasn’t really going to be able to exploit it until I’d have time to sit and go through it all.’

When asked if there is anything he would have changed about his career, Adrian says emphatically: ‘No. Don’t forget, for a long time I just considered it to be a sabbatical. I thought that sooner or later I’d have to go back to teaching or get a proper job. I guess it was that that helped me through – the fact I didn’t really care gave me a bit of a cavalier approach. If I’d taken it too seriously, I wouldn’t have done what I did. A lot of the photo sessions I got involved with were completely speculative; I wasn’t necessarily being hired to do it. There was no money in it; it was just a great thing to do.’

Adrian Boot is one of Britain’s best-known music photographers and began his career in the early 1970s freelancing for NME, Melody Maker, The Times, The Guardian and The Face. As staff photographer for Melody Maker, he photographed some of the most famous faces in music. He has worked worldwide on a variety of projects. www.urbanimage.tv

40 Years of Punk is at Proud Camden, The Horse Hospital, Stables Market, Chalk Farm Road, London NW1 8AH until 8 January 2017. www.proudonline.co.uk