With the rise of citizen journalism and social media, people have greater exposure to pictures of conflict than ever before. There are fears from some that, perhaps, the increasingly graphic nature of these images has desensitised us to what we are seeing. At the time that Philip Jones Griffiths’ Vietnam photographs were taken, however, they were some of the first to show the public the full extent of the horrors of war. What strikes you now, looking back through the archives, with our more jaded eyes, is how shocking and moving they remain.

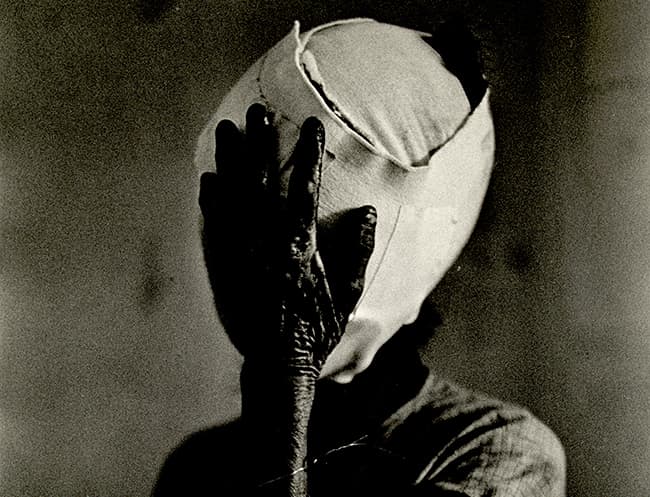

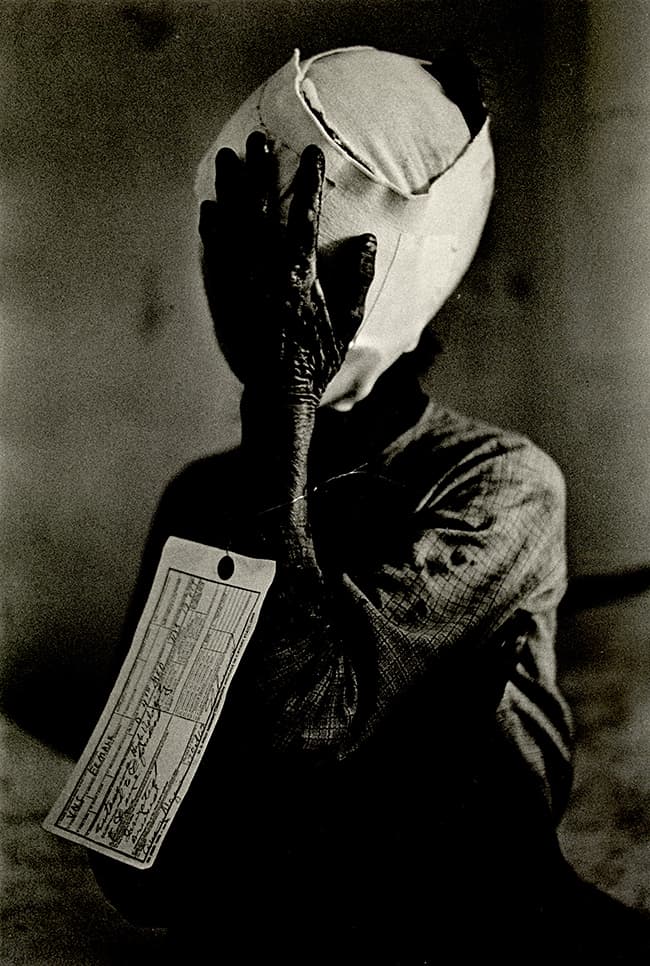

“VIETNAM. This woman was tagged, probably by a sympathetic corpsman, with the designation VNC (Vietnamese civilian). This was unusual. Wounded civilians were normally tagged VCS (Vietcong suspect) and all dead peasants were posthumously elevated to the rank of VCC (Vietcong confirmed). 1967”

Philip Jones Griffiths

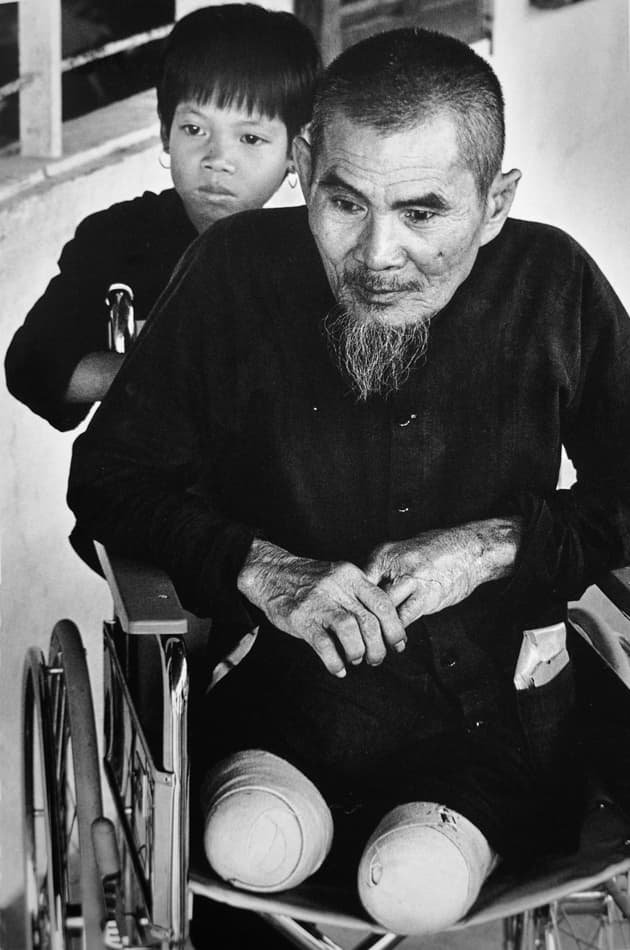

It’s no wonder that Griffiths’ first book on Vietnam, Vietnam Inc, published in 1971, is regarded as one of the pivotal photojournalism books on the period. His natural instinct for communicating emotion and meaning shines through every frame: a young boy cries over the body of his sister; a farm worker looks up to see armed soldiers advancing towards his field; an old man, bandaged stumps jutting towards us, gazes into the distance with dignity and serenity.

‘I think the book is an inspiration to anyone who’s trying to be a photojournalist,’ says Will Troughton, curator of the National Library of Wales, who was tasked with exploring Griffiths’ archives for the current exhibition called A Welsh Focus on War and Peace. ‘You can go through the book time and time again and realise none of the pictures are there as a filler,’ adds Troughton. ‘Every one is there to put a message across.’

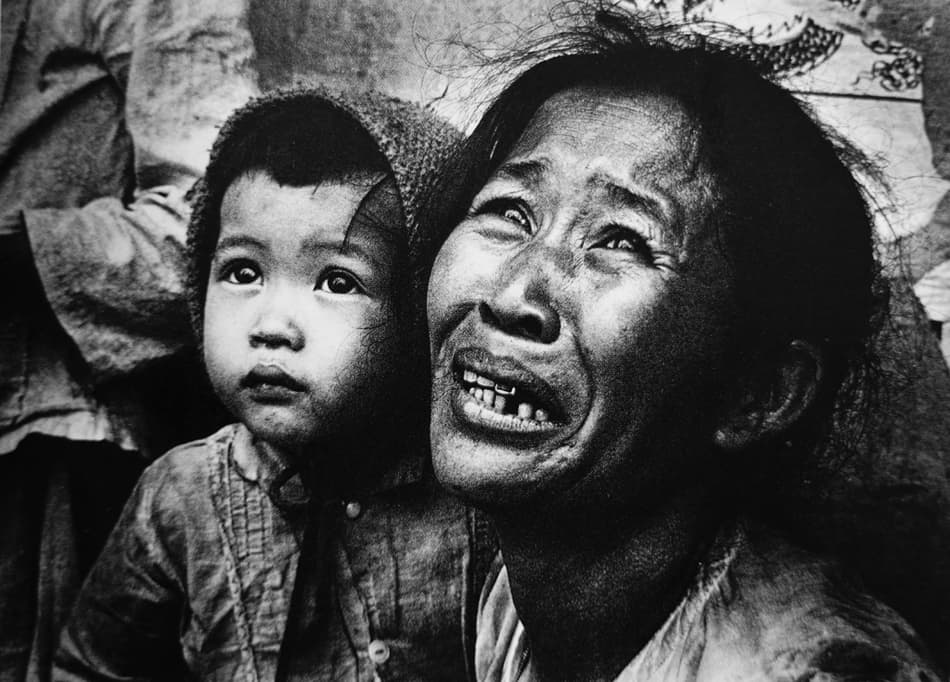

“VIETNAM. The Saigon fire department had the job of collecting the dead from the streets during the Tet offensive. They had just placed this young girl, killed by U.S. helicopter fire, in the back of their truck, where her distraught brother found her. When The New York Times published this photograph, it implied there was no proof that she was killed by American firepower. 1968” Philip Jones Griffiths

Creating a narrative

What Griffiths does so well is use framing, juxtaposition and human expression to create a story in each image and help you connect with what you’re seeing. The captions are integral in enhancing this narrative and evoke a feeling of immediacy.

A young Viet Cong boy lays dying: the caption tells us he fought for three days with his intestines strapped to his body in a cooking bowl. A child chained to the bed goes berserk whenever he hears helicopters pass by: he is reminded, we are told, of when his mother was shot, dropping him from her arms. Young Vietnamese patients lay in hospital beds, their expressions calm, but Griffiths explains they are not healing fast enough and so have been left there to die.

‘The captions tell you so much,’ says Troughton, ‘and help to inform you far more about what’s going on. By giving you context, these descriptions allow you to relate to the photographs far better.’

“VIETNAM. The battle for Saigon. American G.I’s often showed compassion toward the Vietcong. This sprang from a soldierly admiration for their dedication and bravery; qualities difficult to discern in the average government soldier. This VC had fought for three days with his intestines in a cooking bowl strapped onto his stomach. 1968”

Philip Jones Griffiths

What makes his images most striking is his ability to capture the deep-seated calm and dignity of the Vietnamese people in the face of horror. Griffiths had a great affinity with the Vietnamese, seeing in their quiet rural ways echoes of the people he grew up around in Wales.

‘I think it was because they were both rural agrarian communities,’ Troughton tells us, ‘but in both he said there was a sense that you took everything in, but kept it close to your chest. I think what makes his pictures special is that the people he portrays are always allowed to retain their dignity, even when they’re suffering.’

“VIETNAM. Quang Ngai. No one was spared – the old, the young – once I even saw the x-ray of a fetus with a bullet through its brain. 1970” Philip Jones Griffiths

Although many of his images show the American soldiers as an impersonal force, juxtaposed against the shock and fear of the rural Vietnamese population, others do portray sympathy with the soldiers, showing their vulnerability and acts of kindness.

‘I think he sees the GIs as victims too,’ Troughton says, ‘because they were kids, 18 or 19 years old, from farms and factories, being given a gun and sent off to fight against a very experienced guerrilla army in the form of the North Vietnamese. In the 1950s they kicked out the French with their guerrilla tactics, so they’d been fighting for the best part of 20 years.’

“VIETNAM. The battle for Saigon. Pity the poor fighting man in Vietnam. The problem was always too much water or too little. In the early days of the war, water was shipped from California, the indigenous sort considered unsafe. Later it was made “palatable” with huge quantities of chlorine. Wiser men know to fill up with the natural variety. 1968″

Philip Jones Griffiths

Changing opinions

Although he may not have blamed the GIs themselves, some of Griffiths’ pictures do have an anti-American slant: a fact that didn’t always help him get commissions. However, his book had a great effect on the American people. The tide of war was already changing, but his pictures, and ones like it, helped visualise what was really going on in a way words alone could not. Troughton says: ‘I think it was a contributing factor that there was this book here actually showing people what they were perhaps hearing or being told by GIs coming back, but the book laid it out on page after page, 300 photos, really showing people what was going on.’

“VIETNAM. The battle for Saigon. Refugees under fire. Confused urban warfare was such that Americans were shooting their staunchest supporters. 1968” Philip Jones Griffiths

Many of the images the public had seen were in some way censored, says Troughton, sometimes by the photographers themselves, in order to get their images published. ‘He was coming from a different angle,’ he adds. ‘Most of the pictures that were being published showed the American point of view – how the Americans were winning the war and how bravely the GIs jumped out of helicopters. When it came to Griffiths’ portrayal, he was showing what was happening on the ground to the ordinary people who weren’t combatants, but who were caught up in this. It’s an aspect that I think had been overlooked. It shocked people when they saw what was really happening.’

“VIETNAM. South Vietnam. Phu Me. As a Young child, this boy had been in the arms of his fleeing mother as she was hit by machine-gun fire from a helicopter outside their home. He survived, but went insane and spent his life chained up to his hospital bed. When helicopters passed overhead he went berserk trying to shut out their sound. 1970” Philip Jones Griffiths

Getting the shots

But getting the images wasn’t easy. Travel to Vietnam was expensive and Griffiths had to pay for the trip on the back of other commissions. One scoop, on a trip to neighbouring Cambodia where he spotted Jackie Kennedy on a clandestine holiday with Lord Harlech (a former British Ambassador to the US), helped pay for much of his needs.

Griffiths faced challenges travelling around a war-torn landscape. ‘The US did provide facilities for photographers,’ says Troughton, ‘of course he [Griffiths] kept fairly quiet about his real reasons for what he was doing. As far as they were concerned, he was just another photographer.’

“VIETNAM. The battle for Saigon. U.S. policy in Vietnam was based on the premise that peasants driven into the towns and cities by the carpet-bombing of the countryside would be safe. Furthermore, removed from their traditional value system they could be prepared for imposition of consumerism. This “restructuring” of society suffered a setback when, in 1968, death rained down on the urban enclaves. 1968″

Philip Jones Griffiths

Many of the other press would not leave Saigon, getting their briefings from the US military, but Griffiths didn’t believe the official line. He was one of only an estimated third of the Saigon press corps who did go out, claiming to have visited every province in Vietnam on his own to find out what was going on, often in dangerous situations. Troughton recalls finding one slide in the archive, that simply says: ‘Huê´, the city where I nearly got killed.’

Many of Griffiths’ images are taken in the midst of danger, sometimes showing people in the process of dying or who were killed soon after. With little ability to intervene, Griffiths also had to deal with the horrors of what he saw. He would often recount in interviews years later that he still suffered flashbacks, although at the time he was able to disconnect. ‘Griffiths says when he had been photographing one of the hospitals he just took the pictures and he did the crying afterwards when he got home and saw them,’ says Troughton. ‘I think he was able to adopt this persona where he simply took photographs; he was composing them, but in a way he wasn’t seeing what was there. He was seeing it as a photographer.’

“VIETNAM. South Vietnam. Quang Ngai. This group was not recovering from surgery so, to free up scarce beds, they transferred to an outbuilding to die. The determination was made by the hospital’s solitary Spanish surgeon. There was no way he could operate on everyone; he explained with tears in his eyes, “Every morning I have to play God – deciding who will die and who I will give a chance to live.” 1967″ Philip Jones Griffiths

Griffiths knew the work he was doing was important. He was a firm advocate of photojournalism’s ability to document the truth – something he put into practice as a lifelong member of Magnum and its president for five years. However, he felt the agency was moving away from its original focus of reportage.

‘I think prior to the age of digital photography – which he [Griffiths] didn’t like – he felt that a picture didn’t lie, what could be written may or may not be truthful, but if you put a picture in front of someone that was absolute truth. That’s why he felt photography was so important.’

Framing

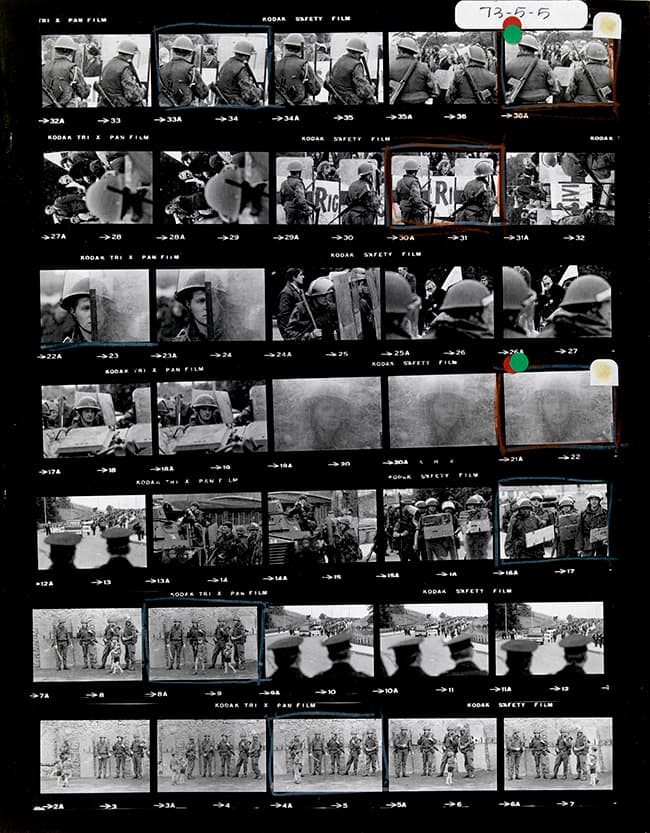

‘Soldier with bulletproof shield’ Northern Ireland, 1973. Cover of Griffith’s Dark Odyssey retrospective book

A look through Griffiths’ contact sheets is quite revealing, and gives an insight into how he composed his pictures. He claimed he only ever put the camera to his eye for three seconds to take a picture, and believed good composition on its own wasn’t enough to make a shot – it also had to have strong content.

Equipment

Philip Jones Griffiths used a wide array of cameras over his career, and had phases where he favoured different models. The cameras shown above – possibly the ones used in Vietnam, where he used Nikon Fs and Leicas – were found in boxes in his archive alongside a number of Olympus bodies, Contaxes, Minoltas, underwater cameras, panoramic cameras, digital cameras and small compact cameras.

Film use

Griffiths was heavily influenced by Henri Cartier-Bresson and preferred shooting in black & white, but the desire to finance his trips meant he needed to sell images whenever he could and magazines wanted colour. He shot colour slide film, favouring Kodachrome or Ektachrome, and then printed in black & white for his own use. However, he felt new film tended to have a slightly green cast. Having trained as a pharmacist, he came up with his own method of incubating the film in a dark box on the roof of his hotel in Saigon, using the reaction from the heat of the sun to get rid of the green cast.

Griffiths’ legacy

Griffiths would publish two more books about Vietnam, Agent Orange and Vietnam at Peace, returning to the country more than 20 times. He also worked in Northern Ireland, Cambodia and visited over 100 countries in his career, often seeking out stories himself rather than waiting for a commission.

Griffiths died in 2008, and left a legacy of work that remains an important part of history. His archive offers a wealth of contact sheets, cameras, documents, personal papers and artefacts stored at the National Library of Wales.

The exhibition, Philip Jones Griffiths: A Welsh Focus on War and Peace, runs until 12 December at the The National Library of Wales, Aberystwyth, Ceredigion SY23 3BU. Tel: 01970 632 800 or visit www.llgc.org.uk