Nick Brandt first fell in love with Africa in the mid-1990s when in Tanzania directing the video for the late Michael Jackson’s single Earth Song.

In the early 2000s he decided to swap moving pictures for stills, and despite spending almost a decade producing the book trilogy On this Earth, A Shadow Falls and Across the Ravaged Land – the clue is to read the titles out together – Nick still felt driven to highlight the plight of animals in East Africa.

Wasteland with rhinos

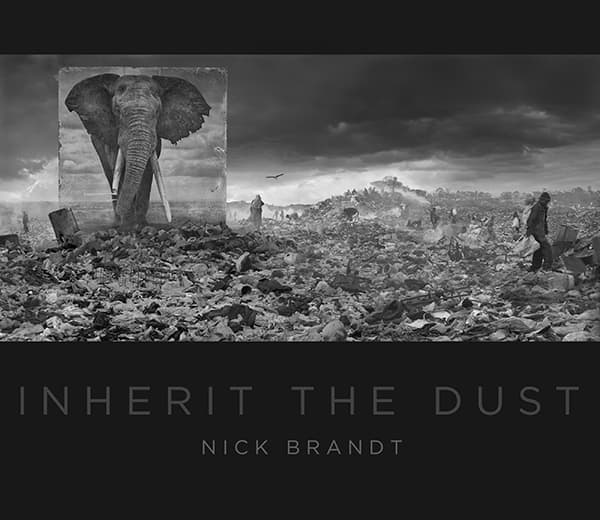

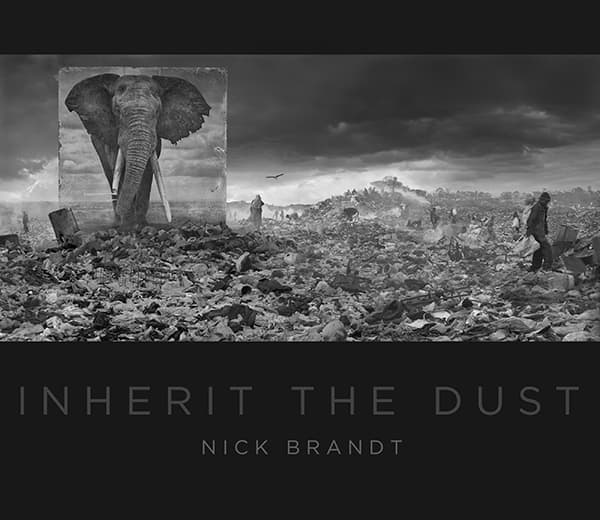

The result is Inherit the Dust, a striking collection of fine-art images that show large photographic panels of animals positioned and shot in landscapes where they had previously roamed, before mankind claimed and developed the land.

Down a phone line from his California home, in a clear English accent, Nick explains: ‘Having worked non-stop for years, I was planning on having a break… but I was so disturbed by the escalation of devastation, I just felt, “You know, I still haven’t really covered it”. What I had done up until that point was not enough.

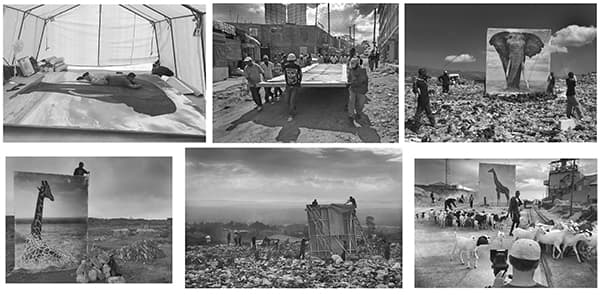

‘The idea for Inherit the Dust kind of came into my head and I just ploughed into it and didn’t stop until I finished it two years later. The first nine months were basically going through my old contact sheets and finding stuff that was never used for one reason or another, good or bad. Then doing tests on my [US] mountainside, where we would build panels – up to 10x7m – and print up what we thought were the best animals at life-size, and then just prop them up and take photographs to see if they looked life-size. If an elephant is 12ft [3.6m] high it should be that big on a panel.’

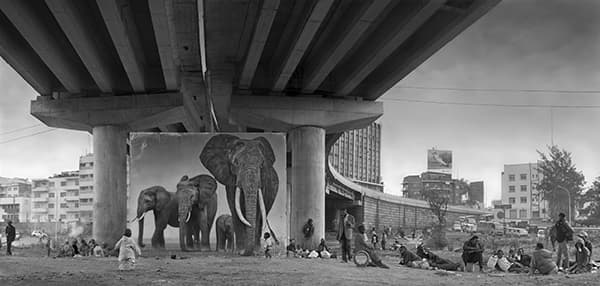

Underpass with Elephants (Lean Back, Your Life is on track), 2015

Locations across Africa were scouted for around nine months before Nick travelled there to shoot. ‘The crazy thing is, after all that time and money spent, by the time I got there the locations often fundamentally changed,’ says Nick. ‘They had built up into things that looked like they had been there for a long time. I was worried when I first came up with the idea that it was going to be too melodramatic and exaggerated. But, actually, when I look at the overall final body of work, it really doesn’t begin to capture the true extent of the out-of-control expansion and development of man into wilderness areas.’

Choosing images and locations

Having delved into his back catalogue of contact sheets and negatives, Nick came up with a selection of animal portraits – including elephants, giraffes, rhinos, chimpanzees and lions – that he felt would work on large-scale panels. ‘That chimpanzee in the alleyway, for example, I thought I had other chimpanzee photographs that were more immediate, more direct and here’s this chimpanzee just kind of looking down at the ground,’ says Nick.

‘But when you put that photograph of him in that alleyway, with that stream of fetid sewage [flowing past], suddenly that looking down informs the overall photograph. It makes it appear as if he is lamenting the loss of the world that he once knew.’

Alleyway with Chimpanzee, 2014

Nick’s crew spent significant time building up the huge image panels in situ. One of the principal reasons the project took as long as it did was because building the huge frames took many, many hours.

‘[The workers] were hauling them up and battening them down to be ready for rain and wind,’ says Nick, ‘and then the process of waiting for the clouds to come and for people to get used to the situation – it’s a four-month process just for 30 images.’

Behind the scenes

Indeed, some of the chosen locations changed while the crew were still working on the ground. ‘I didn’t even know about the quarry until I was shooting by the side of a highway and [the original] ‘Quarry with Lion’ shot wasn’t working – it was really boring. I left my crew of 20 sitting by the side of the highway and just drove off knowing I had to find better.

We spent the afternoon driving and right at the very end of the day I looked down over the edge of the road and there was this massive quarry. The moment we drove down I went: “This is it; get everybody over here”. The beauty of shooting in Kenya with a very good location manager and producer is that the very next morning we were in there – they were so good at turning these locations around super-fast.’

Quarry with Lion, 2014

One key element of the final images is that the panels fitted almost seamlessly into the real-life landscapes in which they were set up. In fact, Nick travelled around the locations with miniature prints of all the ‘panelled’ animal images, so he could hold them up and work out if, and where, they would fit into the developed landscapes.

‘I was absolutely terrified that it would just appear to be Photoshopped. Whenever I turned up on location, I would always look to make sure I could make this panel appear to be genuinely integrated within the scene.’

Shooting on film

Another complication for Nick was his decision to shoot Inherit the Dust with medium-format film cameras, specifically the Mamiya RZ67 Pro IID models. ‘I’d always shot Pentax 6×7 throughout my career, because I love shooting at waist-level,’ he says.

‘I really love looking at that magnified ground glass. Everything I’ve ever done has been shot with waist-level, magnified ground glass – there’s something about the way the image looks on it that really turns me on. I switched to the Mamiya simply for one reason, which was the revolving back. I could crank the back round to vertical format and click away again. I’ve hardly ever used a tripod in all of my photography – that’s why I switched to the Mamiya.’

But, of course, shooting film, as opposed to digital, meant Nick couldn’t see the results immediately. He explains: ‘I am so paranoid and neurotic. I have had instances over the years where film hasn’t come out, like when the camera was only shooting eight shots instead of ten because the winding mechanism was pulling too much film through the camera. With this amount of money being spent on a giant production, I had somebody fly the film back to London every two weeks, making sure the film wasn’t X-rayed at the airport and go straight to one of the last two guys who hand-process black & white film in London. He would process it, do contact sheets, scan the contact sheets and send it to me and I’d know whether it was OK or not.’

Nick estimates he shot around 1,000 rolls of 6x7cm film while in Africa, but the actual shoot was just the start of a much longer process.

Wasteland with elephant

Post-shoot workflow

In the past Nick had used a Nikon Coolscan 9000 to scan his work, but he reveals: ‘This work had to be drum scanned. However, it costs so much money when you’re scanning hundreds and hundreds of 6x7cm negs that I would scan first on my crappy Nikon 9000 scanner. I’d see what worked, do some super rough comps and only then send off the select for drum scanning, but even then we’re talking tens of thousands of dollars.’

In order to compose the 30 finished images for the Inherit the Dust book, and its different exhibitions around the world, it was a case of months of post-production work for Nick, painstakingly stitching together his negatives to create the final images.

‘With film you have to go through all the negatives looking with your 20x magnifier on your lightbox going, “Does that look like it’s kind of the right focus?”’ says Nick.

‘Take the time, scan it, look at it, drop it in and go: “No, OK, let’s look for another one”. This is why it took ten months. Had it been digital, I could have done the post on this in half the time.

Quarry with Giraffe

‘I spent probably about ten months working on these 30 photographs with other stuff going on, like designing the book. Each photograph took about a week to process. Each final photograph is constructed of, on average, six to eight consecutively taken frames that had to be seamlessly blended to hold up when viewed as a 12ft-long print. Between that and painstakingly scanning neg after neg… that took time.’

Nick recalls: ‘If you add up all the money that I spent by shooting film and the process I had to go through: supplying the film, shipping it down to Kenya the expensive way so that it avoided being X-rayed, going through this company at Heathrow and it goes through this machine that shows them that it’s not going to be any explosive. Then you’ve got the film and now you’ve got to send it back with somebody – a special courier on a plane. Then you’ve got to process it and do your contact sheets and then you’ve got to pay for the scanning. I worked it out in one panic-stricken moment that it probably added another US$80,000 [around £55,000] to the process instead of just shooting digital.’

Factory with Rhino, 2014

The final outcome

It’s clear from talking to Nick that he is an incredibly driven individual and, despite the obvious complexities involved in his work, he admits that he simply ‘can’t imagine not finishing’ any project. So what motivates him?

‘First of all, I take photographs purely for myself,’ he says. ‘It’s never for other people. I think that’s a road to artistic mediocrity. You should just take what obsesses you and then, along the way, if other people respond, that’s great. I’ve been very lucky in my career so far that people have responded and I’ve been able to make a living from taking photographs that are just completely for me. However, as, clichéd and corny as it sounds, I want to make the world a better place. I want people to see the photographs, see the original work, and see the animals as sentient creatures that are equally worthy of life, and [respectful treatment].’

Wasteland with Lion, 2015

The Inherit the Dust exhibition is being shown in various countries – in slightly different versions – and can be seen for the first time in the UK during the Photo London art fair in the Atlas Gallery, Somerset House, from 19-22 May.

So what does Nick want to achieve with the project? ‘With this new body of work it’s not enough that concerned, sympathetic people see these photographs and go: “Oh yes, isn’t it awful?” It’s not enough because what are we doing about it? What really needs to happen, and I don’t know how to go about it yet… but basically I want this work to be seen by those in a position to do something about it – politicians and industrialists – and to talk to them and go: “Look at what you’re doing and look at the long-term.”’

He adds: ‘Maybe I’m being completely naïve, but you have to try – look at the short term: the impact of environmental destruction for short-term economic gain versus what you can do when you are considering the environment and the pragmatic, long-term economic benefit of doing so. Even from their capitalist, materialistic point of view there’s still something to be gained out of that. But of course those with power and money have far, far, far more influence than the masses of us who don’t have that influence.’

Inherit the Dust by Nick Brandt, Distributed Art Publishers, £45, hardback, 128 pages, ISBN 978-0-69252-054-3.