Photographing all 42 of England’s Anglican cathedrals made the late Magnum photographer Peter Marlow re-examine his homeland. His partner Fiona Naylor talks to AP about Peter’s epic project and ongoing touring exhibition

Most of us have played a variant of the classic Top Trumps game, launched in the 1970s. In the Anglican Cathedrals of Britain version, players ‘trump’ each other with statistics related to height, external length and number of bells.

Now, a children’s card game might not seem the most obvious catalyst for a photographic project, but the late Peter Marlow (member and two-time president of Magnum Photos) was an original thinker and liked to draw inspiration from unusual sources.

St Paul’s Cathedral, 2011. Image credit: Peter Marlow foundation

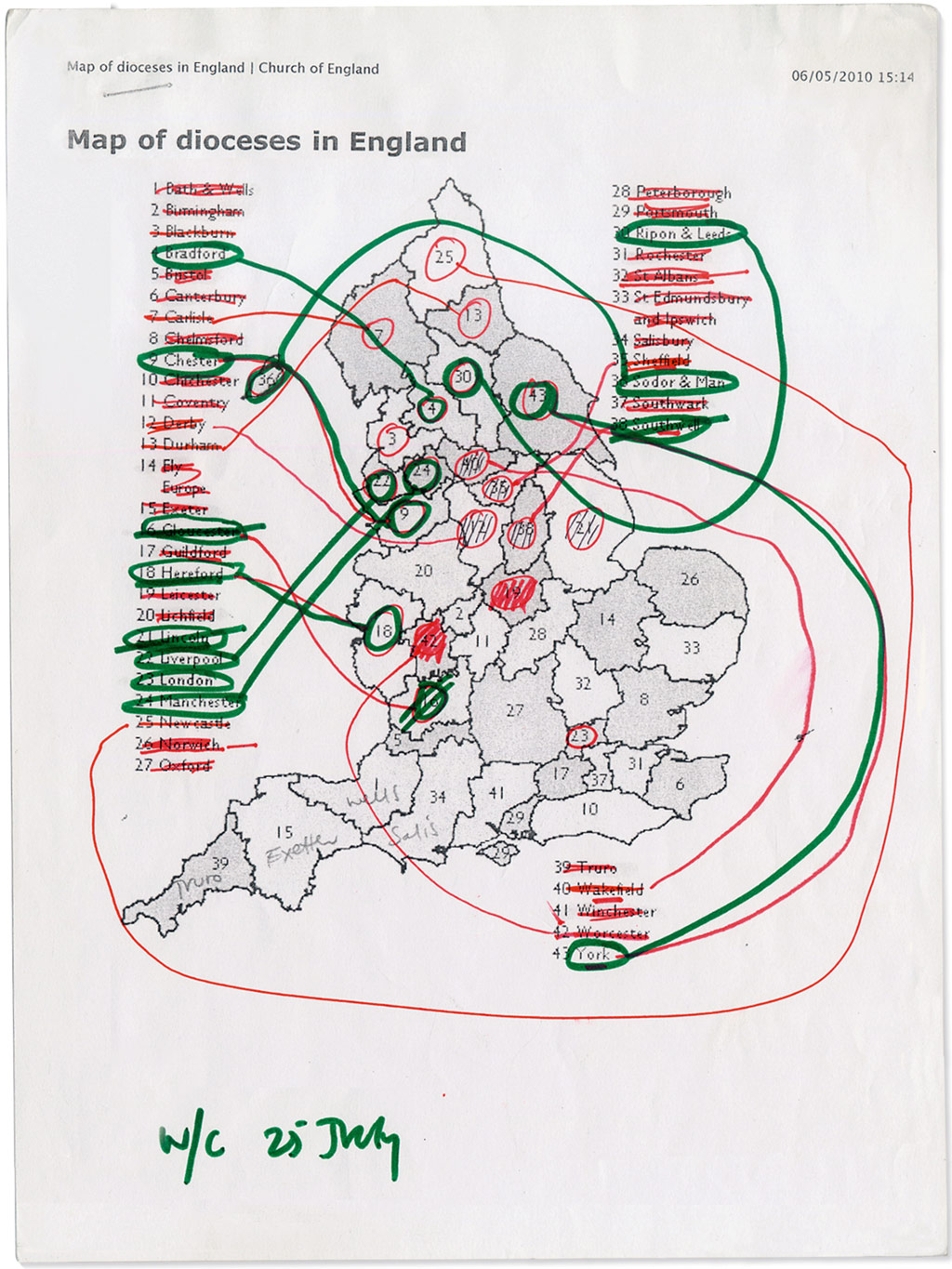

In 2008 Peter was commissioned by Royal Mail to produce six images of cathedrals to be used on a set of commemorative stamps. Once the project was complete, he took his Top Trumps cards (along with a copy of the 1989 book English Cathedrals by Edwin Smith and Olive Cook) and set himself the challenge of photographing all 42 of England’s cathedrals.

If you are inspired by Peter’s project to have a go at architectural photography yourself, check out our guides to fine-art architectural photography and black and white building photography.

The enduring appeal of cathedrals

‘Peter was fascinated by history, and even at a young age he understood that cathedrals are part of what this country is,’ says Fiona Naylor (Peter’s partner and chair of the Peter Marlow Foundation). ‘It’s not just about religion, it’s also about society, crafts, architecture and the evolution of a building – he was fascinated by all of that.’

Southwell Minster, 2011. Image credit: Peter Marlow foundation

The timing of the Royal Mail commission was serendipitous: Peter wasn’t working on a long-form project at the time and the structure and taxonomy of the ‘42 cathedrals’ idea really appealed to him. Also, having travelled to more than 80 countries during the course of his career, he was eager to explore his homeland with new vigour.

‘He talked about it being a bit of a pilgrimage …a way of re-examining what England was,’ recalls Fiona. ‘You spend your whole life travelling around the world and then you suddenly realise you’ve never been to Chester!’

Bradford Cathedral, 2011. Image credit: Peter Marlow foundation

Much of Peter’s early work could be classed as short-form photojournalism, but the personal long-form projects he embarked on were hugely important to him. In the late 1970s, for example, he worked alongside fellow Magnum photographer Chris Steele-Perkins to document the rise of the far-right, even covering the infamous anti-immigration riots of Lewisham in 1977, where members of the National Front clashed with demonstrators.

What’s more, in the 1980s and 1990s he spent eight years photographing the declining conditions in inner-city Liverpool – a location rich in maritime history that was struggling to cope with the fallout of deindustrialisation. ‘He enjoyed working on projects with a continuous thread where he had a number of years to get things done,’ explains Fiona.

St Albans Cathedral, 2010. Image credit: Peter Marlow foundation

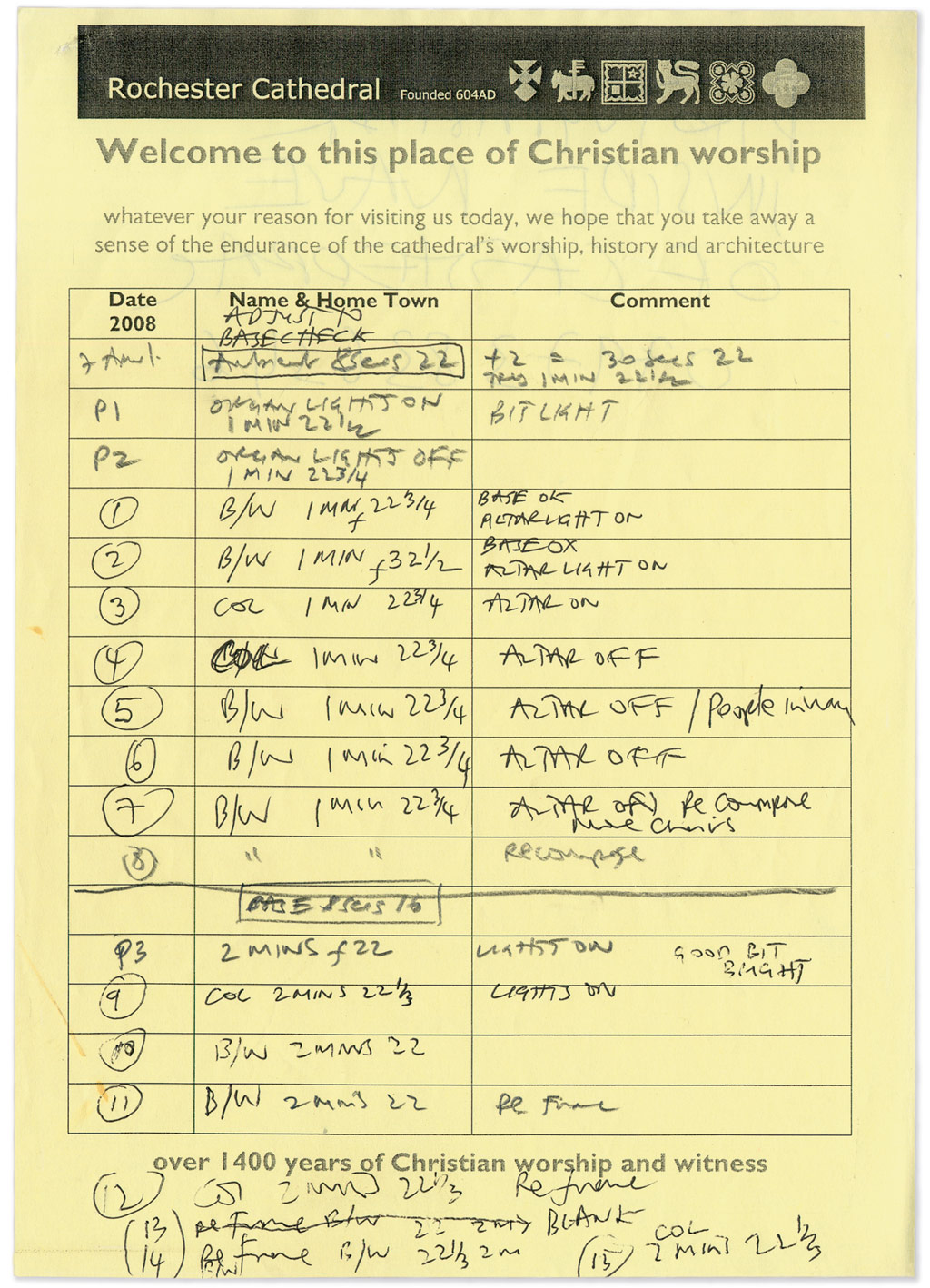

The English Cathedral project took Peter three years to complete and didn’t come without its challenges. From the outset, he decided to photograph the buildings empty, from the same position if possible (looking east towards the nave and altar) and in natural daylight. ‘It’s the way people would have experienced the cathedrals when they were first built,’ says Fiona.

Capturing the best light in cathedrals

‘Peter wanted to shoot with the dawn light coming in – they all face the same way, so at dawn the light comes in through the east window.’ But capturing this fleeting light was easier in some locations than others. ‘Most of the photographs were taken between April and September otherwise by the time the light came up it was too late,’ says Fiona. By ‘too late’ Fiona is also referring to the arrival of the cathedral cleaners (and the general public).

Carlisle Cathedral, 2010. Image credit: Peter Marlow foundation

As part of his recce Peter would try to find out where all the light switches were so that he could eliminate any artificial sources. But even this could be tricky. ‘In one instance – I think it was Chester – nobody knew where the light switch was, because it hadn’t been turned off for 15 years,’ laughs Fiona. On such occasions Peter embraced the challenges and chose to treat them as part of the process. ‘He wasn’t a person who got stressed by things,’ smiles Fiona. ‘He would always come up with a solution – he was endlessly innovative.’

Peter Marlow photographing St Edmundsbury Cathedral, Suffolk, by Peter’s assistant, Marcio Suster, 2012

To add to the complexities, Peter decided to shoot each cathedral from the same height. Using a six-foot ladder (and the tallest tripod he could lay his hands on) he fitted his Sinar F1 monorail camera with a Sinaron-W 115mm lens and loaded it with Fuji 160 Pro film.

Once in situ he used the rising front of the Sinar to keep the verticals parallel. ‘It was important to Peter that everything was in focus too,’ says Fiona. Using small apertures – between f/22 and f/32 – allowed him to maximise depth of field, but also led to relatively long exposures (between one and five minutes).

Planning notes and map for visits to the northern cathedrals, summer 2011. Image credit: Peter Marlow foundation

Transporting all of this heavy equipment into a cathedral was exhausting, so Peter invented a parking permit that he stuck in his car windscreen so he could park outside the west doors without being challenged – an example of the resourcefulness that Fiona speaks of. Once inside, he removed anything that might be distracting in the final image including posters, bins, prayer books and welcome desks.

‘He did what he could,’ says Fiona. ‘In fact, I would say 50% of the project was spent rearranging, discussing access and planning the shoot for times when there were no particular decorations up!’ Cathedrals have busy programmes of events, so the logistics were complicated.

Winchester Cathedral, 2010. Image credit: Peter Marlow foundation

The living power of cathedrals

For this project, Peter needed to be seriously prepared. If everything was in place in good time, he could concentrate on the experience of being in the cathedral. ‘He did most of the project on his own, and I think that was important to him,’ says Fiona. ‘He wasn’t a religious person, but he felt the power of the space and architecture. He would spend time walking around afterwards, absorbing everything. He took something from being in those spaces on his own.’

Exposure notes for Chichester, October 2011

Now Fiona is enjoying the opportunity to retrace her husband’s footsteps. A few years ago, his project The English Cathedral began touring cathedrals in England, and it’s a trend that Fiona (and the Peter Marlow Foundation) are keen to continue. The next stage of shows will be hosted at St Edmundsbury Cathedral, Wakefield Cathedral, Lincoln Cathedral and Worcester Cathedral (with more dates in 2024). ‘It’s a privilege to be showing the work in these spaces,’ says Fiona.

‘Effectively, we have been given some of the most beautiful galleries in the country.’ Beautiful they may be, but these spaces were never intended to be art galleries, so Fiona and her team have to plan the show around immovable objects such as tombs, pillars and door frames.

Ripon Cathedral, 2011. Image credit: Peter Marlow foundation

Running her own architecture and design practice, Fiona is used to finding workarounds in tricky spaces and she makes sure that she visits each location before work is installed. ‘I go on a recce and talk to the verger, dean or team – it’s part of my own pilgrimage,’ she says. On these visits Fiona looks at the uneven floors, the light and the pillars that could hinder the installation and, like her husband, views them as a natural part of the process.

In fact, some of the quirks delight her. ‘There is some interesting subsidence on cathedral floors,’ she notes, ‘but when you walk over these floors you think about all of the people who have walked over them before you. You can tell the route most people have taken around the space. It’s things like that that get me emotionally – it’s the time the buildings have stood there and what they have seen.’ In short, it’s the spirit of the place.

Here are further details of the touring exhibition of The English Cathedral, which continues throughout this year.

Further reading

Guide to fine-art architectural photography

Master black and white building photography