Photographer Jim Grover spent a year photographing the daily life of local South London priest Kit Gunasekera, to produce his photo essay, Of Things Not Seen: A Year in the Life of a London Priest.

The images convey a strong sense of humanity, warmth and sometimes humour, and offer a unique insight into what it entails to be a Church of England minister working in the community today. It is said to be the first time the daily life of a priest has being recorded in this way.

The project takes inspiration from the 1948 work by W Eugene Smith: Country Doctor, a photo essay that showed a doctor going through many aspects of his daily life and work.

Jim shot over 13,000 images for his project, from which the curator chose 40 for the final exhibition, which runs from 3-20 March on the South Bank in London.

We caught up with Jim to find out more about the process behind this project.

What made you interested in photographing the life of a London priest?

I wanted to find a subject that could form the basis of a year-long, in-depth photo story that fulfilled two criteria: be on my doorstep; and involve people. Kit (his vicarage backs onto our garden) and his ministry (which is all about people) ticked both those boxes.

What were you hoping to show?

I wanted to show what the Church of England ministry is all about in London today: what it is like being a minister; what happens beyond the Sunday service that we all know about; how ministers spend their time and fulfil their roles; the challenges and opportunities they face; and, most importantly, the difference they can make to people in local communities.

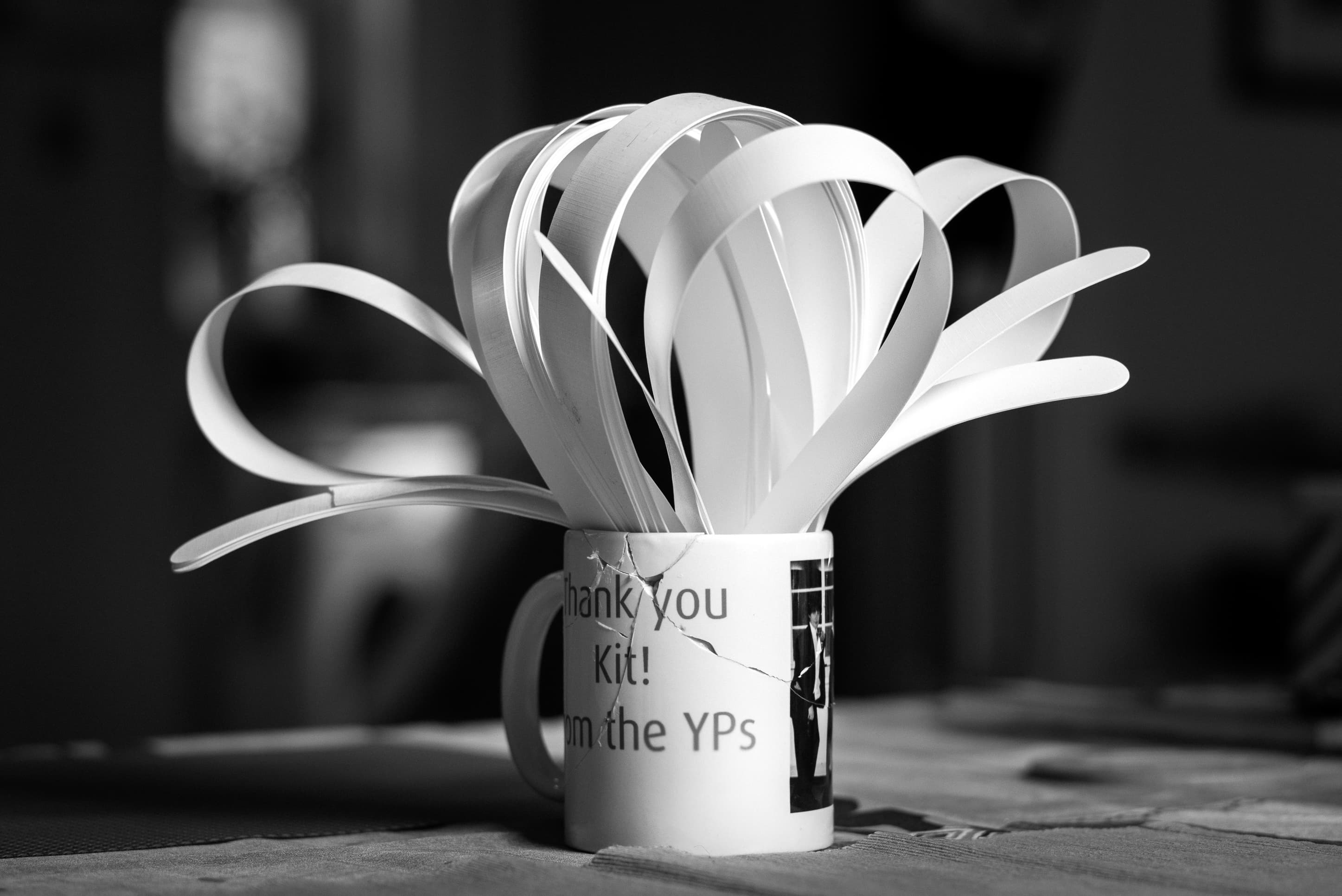

‘Young at Heart’

How did you choose Kit in particular as the subject of this body of work?

At the outset, I was drawn to Kit’s ministry, and thus the role that he fulfills, as compared to Kit himself. I’d only met him once before as a result of our respective cats!

I approached him in his church, which I had never visited before, and asked him if I could shadow him with a camera for a year and tell the story of his ministry, here in Clapham. It was a totally unexpected request for Kit and quite an ask really (imagine if a stranger asked you that). Luckily he said yes!

At prayer

Can you tell us a little about the time you spent with Kit, such as how often you visited him and travelled around with him?

My camera files show that I took images of Kit and his ministry on 63 days over the course of the 14 months (although I shot additional context images on days beyond these). Some days, we’d spend an hour or two together; other days we’d spend most of the day together. Some days I would take a lot of photos; other days I’d take very few and instead spend most of the time talking with Kit and learning about his life, his ministry and what it meant for him.

In terms of the logistics, I needed to work around my day job (I work part time as a consultant). So Kit would let me know in advance some of the things he was planning to do in the forthcoming week or so, and I’d see which ones I could join. Or I’d suggest some things I wanted to photograph, once I knew what his ministry entailed, and he’d let me know when these might happen.

In terms of approach; I wanted to stay true to reportage. Thus, I asked Kit to ignore my presence and to minister as though I weren’t there. I also chose not to share the images I’d captured as I didn’t want there to be any risk of Kit becoming complicit in any way. I did, though, share some of the earlier images so that he could see the sorts of things I was ‘seeing’ and to build his trust.

Making Christ known

Did you have a plan beforehand of what elements of his work you wanted to show?

Not really! The original theme I agreed with Kit was very broad: ‘A year of Kit’s ministry’. I knew nothing about ‘ministry’ so it was a matter of learning and experiencing. I deliberately kept an open mind about the final story I wanted to tell.

Did you hope to evoke the internal/religious elements of his work in a visual way or was the project more about portraying the everyday life of someone in his vocation?

For me, the project was more about seeking to bring life, through images, of what ministry is all about – the everyday life of a minister beyond the things that we identify with them (marriages, funerals and Sunday services, for example).

As part of this project I also analysed Kit’s diary over the course of the year. Thus he attended (and mostly ‘led’) 110 church services over the course of a year, but he also carried out 114 ‘ministry’ roles including care-home visits, pastoral visits to parishioners in their homes or hospitals, and other community events. I have learned that there is so much more to ministry than the church services we all identify with.

Quiz Night: Cod and Chips for Table 5

For you, what are most notable elements about the work that Kit does?

One of the aspects of the role that Kit finds most fulfilling is his pastoral visits; visiting those in need in their homes, hospitals, or care homes. And having accompanied Kit on many of these, I have seen for myself the huge difference that they make.

Imagine you are in need… you have faith. Kit comes to you. He chats.. he reads the bible… he prays with you… he may sing to you… he gives you Communion. He gives you his undivided attention, time and love.

When Kit leaves, the recipient is emotionally stronger, sometimes quite visibly, than when he arrived. What a wonderful gift to be able to give. Many leaders would love to be able to make such a profound impact on those they lead.

The image ‘With Floris’ brings this to life: love… trust… and faith.

With Floris

You mention that an inspiration for this work was the photo essay by W Eugene Smith: Country Doctor. How did this feed into the work that you did?

Because this was my first photo essay I felt it I should study how others have tackled this challenge – and it’s definitely a challenge!

As I explored the genre I was drawn to a few (with quite different approaches and styles): Carolyn Drake, who has just joined Magnum; Chris Killip; and Eugene Smith. Eugene Smith’s work is, of course, legendary. One of his essays, ‘Country Doctor’, was especially interesting for me as it (brilliantly and sensitively) tells the story of how a humble man seeks to make a difference to his local community, essentially working by himself.

The parallels with Kit, and his ministry, are obvious. Looking at Eugene Smith’s and Chris Killip’s work also triggered the decision to shoot my photo essay in black & white (on a Leica Monochrom).

Going to work

Your images often juxtapose symbols of the spiritual with everyday items, such as dog collars in a mended cup, and Iceland bags around an altar. How much of this was intentional?

I was intrigued by the juxtapositions that I saw between what I would call ‘high church’ and ‘everyday life’. And some of these provide, hopefully, some emotive images that will cause the viewer to pause and reflect about ministry, the people who Kit ministers to and what it is like being a minister.

Some of the images are Kit’s ‘tools of trade’ which I also wanted to include, but in unexpected ways.

‘Dog Collars’

Your subjects sometime include people in private or vulnerable situations, such in hospital or praying. Were people generally happy for you to photograph them at these moments?

I was fortunate enough to quickly establish the trust and confidence of those who Kit ministers to, and often with the very briefest of explanations either by Kit or myself.

I know that I am a very sensitive photographer; I always seek to be empathetic and understanding, and that probably helps build trust. I also genuinely love talking with people, hearing their stories and learning about their lives – and in my experience that also goes a long way to building trust and confidence.

Service for day-centre visitors

Many images seem to be done with sensitivity, such as where Kit visits a sick patient, and you show only the hand of the patient. Did you make any conscious decisions about how you would approach taking these type of shots?

There wasn’t, of course, any planning – there couldn’t be, given the reportage nature of the work. Thus I never knew what I was going to experience or see on my travels with Kit around his parish, and that is what made the experience so challenging and rewarding. What I always sought to do was to tell the story of Kit’s ministry, and the relationship he had with the individuals he was ministering to.

But I knew I was also participating in some very intense and intimate moments, and respected these accordingly. Thus, even though I was using a Leica rangefinder (with a very quiet shutter), I would tend not to shoot during a prayer with an individual in their home (waiting, instead, for the ‘Amen’ moment). And there was a moment when a parishioner broke down in tears with Kit; it would have made for some incredibly powerful images, but I put my camera down as it just didn’t feel right.

Pastoral visit

How were the final images for the exhibition selected, from so many?

With great difficulty! Inevitably, as a photographer, there are some images that one wants to hold on to. But it is here that my wonderful curator, Katy Barron, came into her own, holding the tension with me as to what was ‘worthy’ and what wasn’t.

We went through several iterations before we landed on the ‘exhibition 46’ (we had sought to limit it to 40!). Interestingly, if I was doing it again, I’d absolutely force myself to the 40; I am the cause of the extra 6! There is no question in my mind that a talented curator is an invaluable partner, even if it may be uncomfortable at times.

One guiding principle for me throughout was that the final image selection should be representative of Kit’s ministry. My goal has been to bring to life the story of Kit’s ministry, here in South London, in images. And I have applied that ‘lens’ as we have edited the selection down to a final set.

Holy oils

Can you tell us more about the exhibition that will be held in the Gallery@oxo in March?

It runs from 3-20 March daily (11-6pm; admission free). Beyond the beautifully processed, printed and framed images (none of these by me!) I have sought to add depth to the story by providing further background materials for those who are interested. And I have also included a set of images shot by Kit’s congregants: I gave them all a disposable camera to capture their everyday lives.

Please come… and please say ‘hello’. I plan to be in the gallery each day.

See more details of the exhibition

All images © and courtesy of Jim Grover