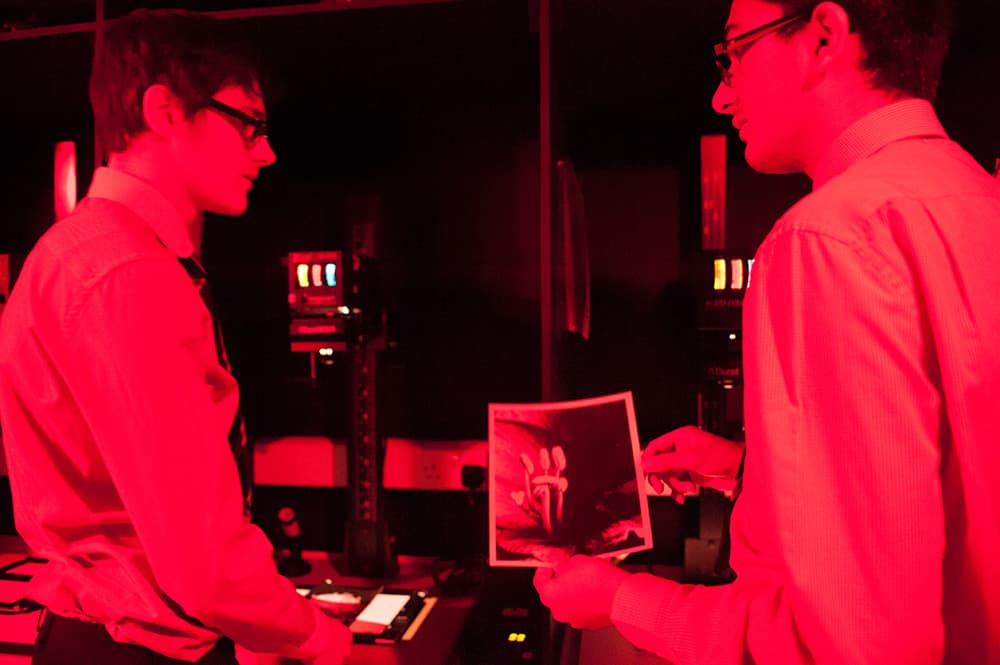

‘How does that happen?’ asked the iPhone-savvy teenager as he watched his first darkroom print appear through the developer on what he thought was just a white piece of paper. Film often fascinates the pupils I teach at school: digital is no longer new. It has lost the ‘wow’ factor.

‘How does that happen?’ asked the iPhone-savvy teenager as he watched his first darkroom print appear through the developer on what he thought was just a white piece of paper. Film often fascinates the pupils I teach at school: digital is no longer new. It has lost the ‘wow’ factor.

Countless young photographers know only digital, and in the entertainment age they are encouraged to consume rather than create. What’s more, many older photographers own film cameras with far bigger ‘sensor’ formats than their DSLRs, but they sit in cupboards unused. So what are these photographers missing, and what are the reasons to try, or retry, film?

1. Film choice

The range of available film is expanding. Kodak Alaris is shortly to reintroduce Ektachrome slide film, and nothing beats a slide show in a darkened room for visual impact. Ferrania’s new plant is reproducing a classic 1950s black & white emulsion called P30. You may be surprised how much film is still being made and used across the world. Sales are increasing each year, according to both Ilford and Kodak.

2. Limited frames

We often frame, edit and shoot more thoughtfully with film. A limited number of frames, as well as a fixed ISO speed, teach us discipline and planning. Having shot Colonel Gaddafi’s portrait, photographer Platon commented, ‘I think I got one roll of film – that’s all I had of him. I remember getting halfway and I still didn’t have it, and I was aware I had six frames left. So you don’t waste one.’ With reversal film, exposure and composition have to be right before you release the shutter.

3. Creative control

Film informs digital photography. Darkroom printing taught Thomas Knoll, the creator of Photoshop, to understand ‘the struggle of trying to adjust an image’, for example. The hands-on, creative control of processing and printing teaches us about light and dark, tones and hues, and how the surface of a print affects its tonal range. It exposes us to the tangible, tactile quality of the printed image in a way that digital rarely does. Each negative is precious: you have carefully processed it. Film informs digital: digital is derived from it.

Film informs digital photography. Darkroom printing taught Thomas Knoll, the creator of Photoshop, to understand ‘the struggle of trying to adjust an image’, for example. The hands-on, creative control of processing and printing teaches us about light and dark, tones and hues, and how the surface of a print affects its tonal range. It exposes us to the tangible, tactile quality of the printed image in a way that digital rarely does. Each negative is precious: you have carefully processed it. Film informs digital: digital is derived from it.

4. Be unique

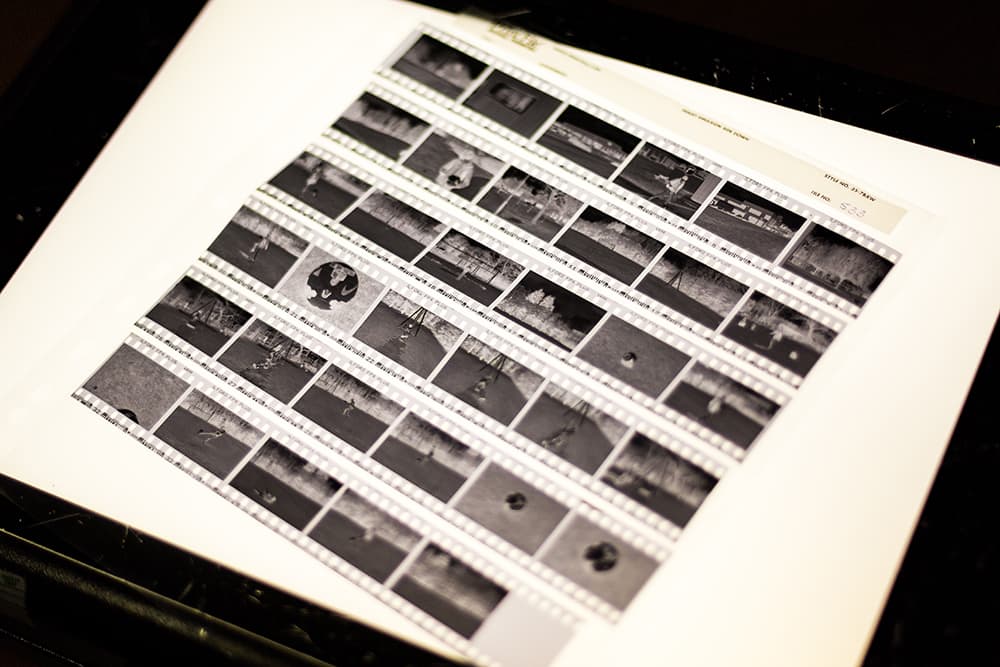

Film has unique qualities. Negative film tolerates over-exposure better than digital, for instance. A 6×4.5in negative shot on a second- hand MF camera offers around seven times the imaging area of an APS-C DSLR, which means less tonal and hue compression. Film is, in many ways, simpler: you can observe each part of the process, and act accordingly. The contact sheet (under reflected light) teaches you to assess an image against its negative (seen with transmitted light). The vast range of film and developer, agitation and exposure combinations possible with film result in a wide range of creative choices for us to explore.

Film has unique qualities. Negative film tolerates over-exposure better than digital, for instance. A 6×4.5in negative shot on a second- hand MF camera offers around seven times the imaging area of an APS-C DSLR, which means less tonal and hue compression. Film is, in many ways, simpler: you can observe each part of the process, and act accordingly. The contact sheet (under reflected light) teaches you to assess an image against its negative (seen with transmitted light). The vast range of film and developer, agitation and exposure combinations possible with film result in a wide range of creative choices for us to explore.

5. Seeing clearly

Film offers creativity without distraction. Most of us view our digital images on an LCD screen, with details about the aperture, shutter speed etc appearing at the same time. We then look at them on a computer with clutter or virtual wallpaper behind them. In contrast when we shoot film the clear view we see through the viewfinder enables us to concentrate on the subject. What’s more, the darkroom is refreshingly free of distractions. Shooting and/or processing film encourages us to be patient, focused and reflective allowing us to enhance our craftsmanship.

Film offers creativity without distraction. Most of us view our digital images on an LCD screen, with details about the aperture, shutter speed etc appearing at the same time. We then look at them on a computer with clutter or virtual wallpaper behind them. In contrast when we shoot film the clear view we see through the viewfinder enables us to concentrate on the subject. What’s more, the darkroom is refreshingly free of distractions. Shooting and/or processing film encourages us to be patient, focused and reflective allowing us to enhance our craftsmanship.

6. Experiment

‘The negative is the equivalent of the composer’s score, and the print the performance,’ said Ansel Adams. Yet many modern-day photographers never print, and only see their images on screen. It’s easy to rely on software presets or conversions. So why not experiment with films, and darkroom papers with their varied tones, surfaces and silver content? Discover Ilford XP2, scanning film, cyanotype, pinhole, sepia toning, emulsion lifts, platinum printing, and a host of other processes and techniques.

‘The negative is the equivalent of the composer’s score, and the print the performance,’ said Ansel Adams. Yet many modern-day photographers never print, and only see their images on screen. It’s easy to rely on software presets or conversions. So why not experiment with films, and darkroom papers with their varied tones, surfaces and silver content? Discover Ilford XP2, scanning film, cyanotype, pinhole, sepia toning, emulsion lifts, platinum printing, and a host of other processes and techniques.

7. Darkroom

Analogue widens the appeal of photography. Many higher-education institutions teaching photography still have darkrooms, and film is proving increasingly popular with students. Our school’s darkroom has been enlarged to meet demand. (If you don’t have access to a school or college darkroom you can always hire one. If film is new to you, seek out those who can pass on their skills. If you have a spare film camera, teach a young person how to use it. It can also help to join an online forum or collective such as the RPS Analogue Group where I work as vice chairman. (For more details visit rps.org/special-interest-groups/ analogue.)

Analogue widens the appeal of photography. Many higher-education institutions teaching photography still have darkrooms, and film is proving increasingly popular with students. Our school’s darkroom has been enlarged to meet demand. (If you don’t have access to a school or college darkroom you can always hire one. If film is new to you, seek out those who can pass on their skills. If you have a spare film camera, teach a young person how to use it. It can also help to join an online forum or collective such as the RPS Analogue Group where I work as vice chairman. (For more details visit rps.org/special-interest-groups/ analogue.)

8. Consider used equipment

There are many great used film cameras available. While we wait for a camera manufacturer to realise the latent demand for a new film SLR (more affordable than Nikon’s F6), make the most of the range of used film cameras on the market. There are still camera repairers who can put new foam in SLRs (a common fault) and service film cameras, many of which do not have battery hungry displays and are lighter and cheaper than their full-frame digital equivalents.

There are many great used film cameras available. While we wait for a camera manufacturer to realise the latent demand for a new film SLR (more affordable than Nikon’s F6), make the most of the range of used film cameras on the market. There are still camera repairers who can put new foam in SLRs (a common fault) and service film cameras, many of which do not have battery hungry displays and are lighter and cheaper than their full-frame digital equivalents.

9. Refine your skills

Digital technology (which I’d like to point out I use daily) can effortlessly de-skill us: some modern photographers, for example, do not know how to focus manually. All of the convenience that digital gives us can make us lazy. Film’s creative potential, quality and technology provide a vast range of opportunities to learn new skills, deepen our understanding and produce results visually quite different to digital. So broaden your horizons, discover something as old as the art form but as new as the age. Try film.

Digital technology (which I’d like to point out I use daily) can effortlessly de-skill us: some modern photographers, for example, do not know how to focus manually. All of the convenience that digital gives us can make us lazy. Film’s creative potential, quality and technology provide a vast range of opportunities to learn new skills, deepen our understanding and produce results visually quite different to digital. So broaden your horizons, discover something as old as the art form but as new as the age. Try film.

David Healey ARPS is the photography tutor at King Edward VI Aston School, a multicultural grammar school for boys in Birmingham, and vice chairman of the Analogue Group of the Royal Photographic Society. To find out more about the group visit rps.org/special-interest-groups/analogue.