What kind of preparation do you do for a typical live shoot?

I normally get to the venue around 4pm, although that can sometimes be as early as midday if I’m setting up remote cameras for the shoot. Once in the venue, I set up a secure production office backstage for my computer and camera equipment. If I’m setting up remote cameras within the lighting rig, I have to be at the venue while all the trusses are down.

I put all batteries on charge, format cards and clean the sensors. I then connect to the Wi-Fi and start my computer, uploading any outstanding shots. I then grab a camera and scope out the venue. While on tour, the stage set remains the same, but depending on venue sizes, the distance between the stage set and backdrops can vary widely.

I chat with the lighting designer about follow spots. I then check out the pit, the barrier and the stage (looking out for holes in the stage as well as potential danger areas and trip hazards). When the lights go out and the show starts, everything looks very different.

Lastly, I find an easy route to the top and back of the arena to get the huge arena/stadium shots. Doing it before the show starts prevents me getting lost during the show (which has happened!). I then shoot a few shots of the stage production before the show begins and head outside to photograph the venue and the usual line of fans queuing around the block. Depending on the country, you have to have your wits about you as some fans get more excited than others.

By 7pm I have dinner and prepare all cameras for the show. By 8pm the band are usually close to being ready, wearing stage clothes, and this is when we will usually shoot any press portraits needed for that territory. I also pack up all equipment ready to grab and go.

I’ll then photograph the ‘walk-up’ of the band to the stage. I usually get some of the best character shots of the band here as there’s a buzz of excitement in the air. This is always low light, so I shoot at a high ISO at f/2.8 with a shutter speed of around 1/500sec. Once the band is on stage, I put my ear plugs firmly in and make my way to the pit at the front of the stage. Never forget a torch – it’s a difficult journey without, avoiding ramps and cables. Five minutes later and the band hit the stage and my real job begins for the next two hours.

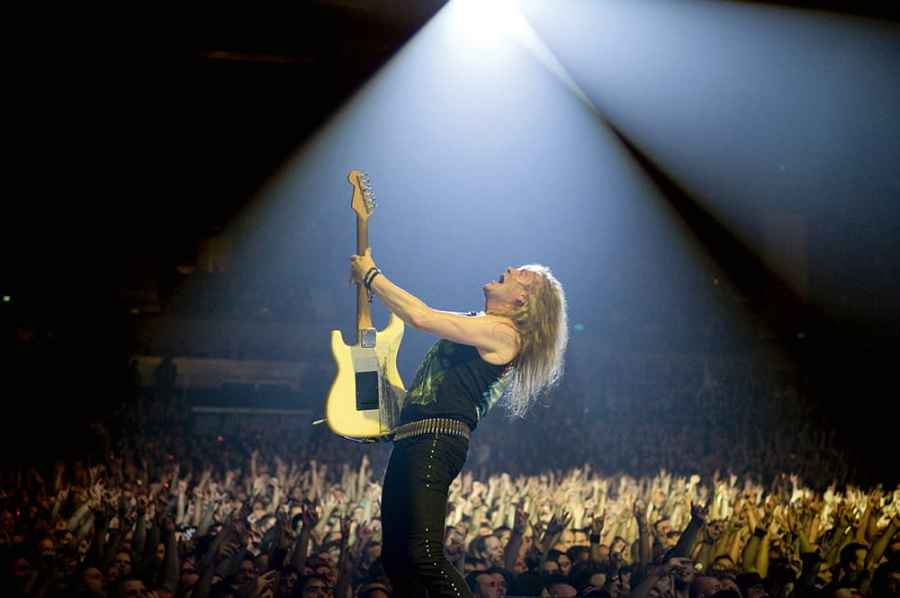

Iron Maiden guitarist Janick Gers live on stage in Brisbane, Australia. Nikon D3, 24-70mm, 1/400sec at f/3.2, ISO 2500

What camera do you currently use and how does it cope with low-light conditions?

Nikon. If you’re shooting low light, then you can only use Nikon. I’ve tested the Canon system and the low light is not a patch on the Nikon’s. The game changer was the launch of the Nikon D3. When that camera was launched it blew my mind, and digital photography made a huge technological leap, making it better than film. I’m currently using the D4s with a D5 on order. A lot of people in the photography world will tell you that more pixels equals better low-light capabilities. I find the opposite is true. The higher the pixel count the lower the quality in low light at high ISO. The D4s is 16 million pixels and the quality at ISO 3200 is outstanding. At ISO 3200 on a 22-million-pixel camera the images are poor without noise reduction.

How far do you dare to crank up the ISO in these conditions?

On a D4s I shoot at ISO 1000- 2000 as standard. If the light levels fall low, then I’ll occasionally shoot at ISO 3200 and if desperate I shoot at ISO 5000, but then use the noise-reduction function in Lightroom.

In seriously dark conditions I use my Zeiss Otus f/1.4 lens. This is an outstanding lens for sharpness and is a wonderful portrait lens.

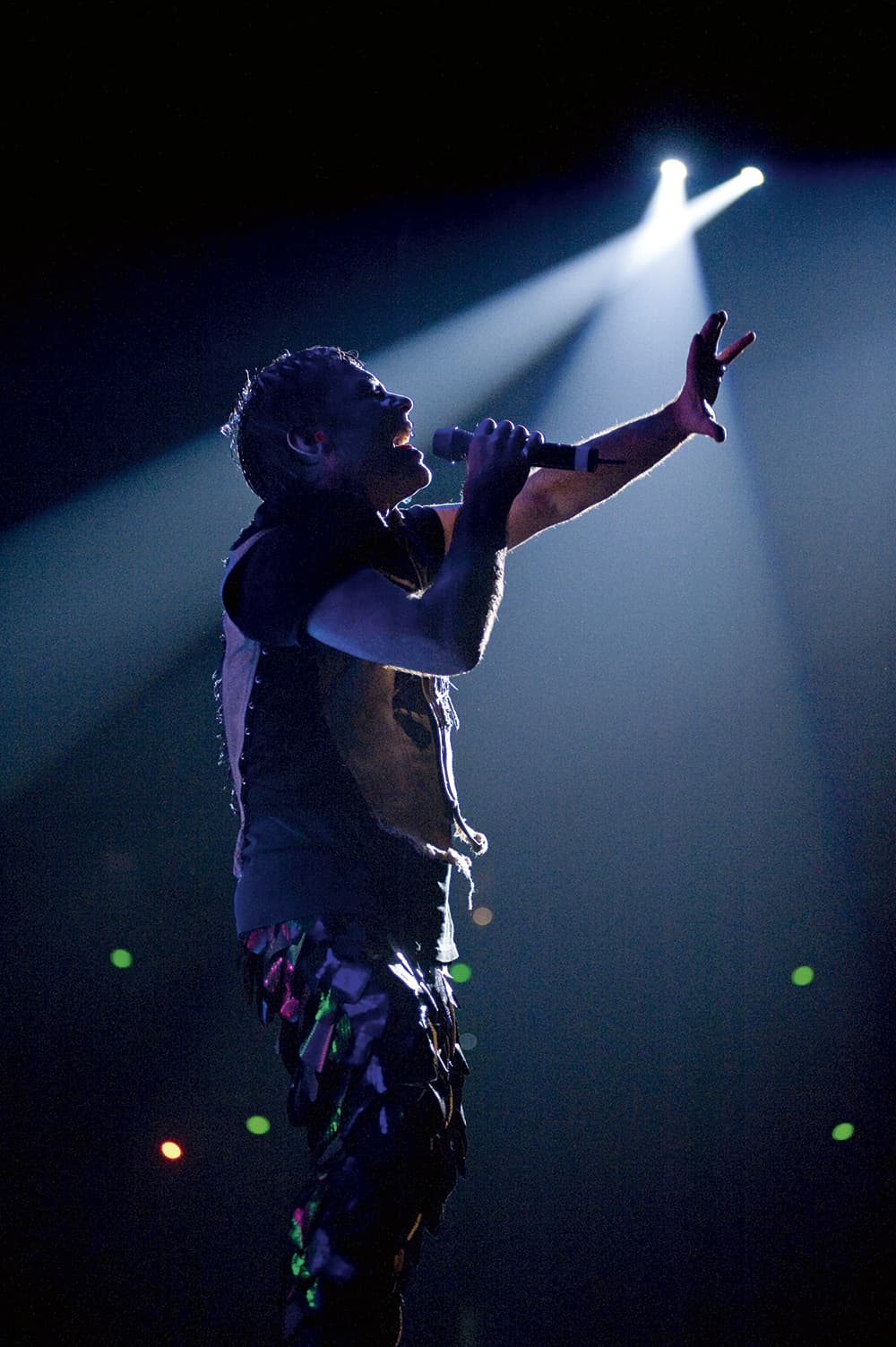

McMurtrie turns his attention on the rapturous crowds. Nikon D35, 24-70mm, 1/200sec at f/2.8, ISO 2000

Is it difficult to shoot scenes in such low light when the band is constantly moving?

Definitely. I only ever use manual exposure, choosing to change shutter speeds with a flick of my thumb, rather than relying on an auto exposure mode, which half the time will underexpose due to the bright stage lights. To catch Bruce Dickinson [singer in Iron Maiden] flying through the air on stage and to keep him sharp, I need a shutter speed of at least 1/800sec. To do that, I need a fast ISO of 2000.

I usually prefocus and wait for Bruce to jump and rattle off about 20 shots in a two-second burst. This method allows me to take one optimum frame.

Shooting Nicko McBrain, the drummer, is difficult because he doesn’t have the luxury of a follow spot. To get shots of him, I have to crawl through the back of the stage set and into the drum area, which is cramped and narrow. Once past the drum tech, I then can only ever shoot on a 16mm fisheye, as I’m incredibly close to Nicko hitting his kit. I then have to focus and wait forthe light to be right before shooting. Auto exposure never works here because of the reflections on the cymbals – it will always underexpose. I also need to keep the shutter above 1/250sec or there’s too much motion blur. Guitarists are usually straightforward but during solos the facial expressions are not always flattering. Iron Maiden use a lot of pyrotechnics and to expose for flames and explosions I’m sometimes shooting shutter speeds over 1/1,000sec. I also have to be in the right position before they fire, and somewhere safe.

At the end of the show, I have literally 30 seconds on the back walkway to get the band and crowd all lit up before a massive amount of pyros fire beneath my feet. I have to have eye contact with the pyro technician or this potentially could be life threatening if I get my timing wrong. I get the shot and quickly turn and walk down the steps off the stage. Usually I’ll feel the warmth of the explosion on the back of my neck just as I turn.

The biggest difficulties music photographers have these days are colour balance and oversaturation from the widely used LED lighting. Most follow spots are a warm tungsten colour, while the stage LED lights are a daylight blue. It is beyond the physics of photography to successfully balance the two perfectly so there is a lot more post-production getting colours to balance.

Iron Maiden’s Bruce Dickenson side lit by two spotlights. NIkon D3, 80-200mm, 1/200sec at f/2.8, ISO 2500

John McMurtrie is an award-winning music photographer. He is also the official photographer for Iron Maiden and his images have features in many global publications. See more at www.picturedesk.co.uk