With raw image conversion software becoming increasingly common and easier to use, should we all now be shooting raw files, or does the standard JPEG still have some advantages?

Raw file conversion can be an intimidating subject for those starting out in digital photography. Noise reduction, sharpening, white balance adjustment – they’re all phrases that can make a novice feel out of their depth, and want to stick to shooting JPEG files. The control that is afforded over raw images should allow for superior image quality compared to the humble JPEG, but many argue that improved processing in contemporary cameras means that shooting raw files is unnecessary and time-consuming.

Even enthusiast photographers may have been put off by the fact that some older, consumer raw conversion software had individual image, rather than batch, processing. Also, and with few exceptions, manufacturers’ raw conversion software can run slowly on some computer systems, so editing can be a long and intensive process.

However, in the past few years, raw workflow software, such as Apple Aperture and Adobe Photoshop Lightroom, has improved the process of editing raw images. The latest versions of both these software packages have many additional features, such as localised adjustment tools, which means that there is often no need for a second image-editing software package. Even the simple Adobe Camera Raw now supports batch processing of raw files, enabling basic adjustments to be made to multiple images quickly and easily.

As computers become faster and software more efficient at handling raw files, is there any advantage still to be had by shooting JPEGs? Despite the advances in raw conversion software, is it still too much effort to shoot raw, for too little added benefit, when faced with the convenience of JPEGs?

What’s the difference?

Software-based noise reduction for raw files allows for more control compared to the in-camera reduction used for JPEG files. This can help remove noise with minimal blurring, which causes detail loss

A raw file is simply the raw information that is produced by the camera’s sensor. In most cameras, each photosite (representing one pixel) is sensitive to one colour: red, green or blue. The amount of light from each different photosite is recorded in the form of a luminance value. If this information were presented as an image, it would look like a mosaic made up of red, green and blue pixels of different levels of brightness.

This forms the majority of the information contained within a raw file, but in this red, green and blue mosaic form it is useless to us as photographers. To render this information as a composite image, it must undergo a process known as ‘demosaicing’. This is where the raw data is transformed using complex algorithms and interpolation to work out a true colour value for each pixel, based on the luminance of each red, green or blue pixel surrounding it. Once this has been done, a graduated image is produced.

When an image is saved as a raw file, the red, green and blue mosaic data is saved, leaving the demosaicing and any colour, contrast, sharpening and noise reduction adjustments to be done via a raw conversion software program on a computer.

For a camera to create a JPEG image, all this demosaicing and any interpolation of the raw data must be done in-camera, along with sharpening and colour adjustments to compensate for white balance or personal taste.

A JPEG image is then compressed to reduce its file size. This is done by applying a compression algorithm that, put simply, finds areas of a similar colour and luminance, and bands them together as one. This is why gradations in blue skies in JPEG image files can sometimes look posterised if they are compressed too heavily, particularly when they are presented at larger sizes.

The pros and cons of raw and JPEG

There are, of course, advantages and disadvantages associated with shooting raw and JPEG files. If their cameras afford them the option, many photographers choose to avoid the dilemma completely by shooting raw and JPEG files simultaneously.

If not, then whether to shoot raw or JPEG files comes down to the issue of quality versus speed and convenience. As raw files contain all the untouched data as it was captured by the camera’s sensor, they allow for greater control when editing the image than JPEG files do. This makes raw files the better option for archival purposes. However, the larger file size means raw images take longer to write to a memory card, which can slow down burst shooting, and use more space on both a memory card and hard drive.

Generally, manufacturers use their own raw file formats – Nikon’s NEF or Canon’s CR2 formats, for example – and fewer programs are able to open and edit these files compared to JPEG images. Adobe has tried to come up with a solution by introducing its DNG format (see below), but while this is slowly gaining popularity it is a long way off becoming a universal raw format.

Although JPEG files take up less memory, they come at the expense of flexibility. However, the format makes up for this in other ways. The vast majority of JPEG files that come straight from a camera have tone curves, noise reduction and sharpening applied to them. This means they are suitable for printing or display straight away, without any further editing. As JPEGs are smaller in size, they are more convenient for sending via email or for displaying on the internet, and as a universal format they can be read by a multitude of different software.

But is the apparent superior image quality of raw images enough of an advantage when compared to the convenience and speed of JPEGs?

There is much more detail recoverable in the shadow areas of the raw file, compared to what can be recovered from the in-camera JPEG

Sharpening

Due to the interpolation process, demosaicing causes most raw files to be naturally soft. When created in-camera, JPEG files have sharpening applied to them, the level of which can usually be adjusted within the camera’s menu system. Often, though, far more detail can be resolved from processing the raw files using image-editing software.

Each manufacturer handles the sharpening of its files in different ways. For example, JPEG files from Olympus E-series cameras are very sharp, as are the company’s ORF raw files. In fact, there is only minimal sharpening that can be applied to an Olympus raw file before it starts to have a detrimental effect on image quality, creating a halo-like effect around details and an increase in luminance noise.

Conversely, when viewed at 100% on a computer screen, in-camera JPEG files from Canon cameras tend to be a little soft. However, even by applying just a low level of sharpening in Canon’s Digital Photo Professional software, a dramatic improvement to the level of sharpness and detail can be made.

So when it comes to sharpening and detail, raw files do have the edge, but how much so will depend on which camera and software is being used, as well as the subject matter. Images that contain a lot of fine detail will benefit more from sharpening, though it is sometimes more flattering to hide fine details, such as when taking a portrait.

When viewed at 100%, it is clear that the JPEG created in-camera is a little soft. Sharpening both the raw and JPEG files shows a slightly better level of detail and sharpness in the raw file

Adobe DNG

Adobe DNG is Adobe’s own raw file format, and stands for ‘Digital Negative’. It is currently used by manufacturers such as Casio, Leica, Pentax, Ricoh and Samsung, and is recognised by a number of software programs. The company hopes that its adoption will help to future-proof raw files.

There is some concern that new cameras will require new raw file formats to be created, which in turn could eventually cause manufacturers to drop support for their existing formats. By being a universal format, Adobe hopes that DNG will get around this issue.

Some manufacturers such as Canon and Nikon are in no hurry to adopt the DNG format, though Pentax now uses it alongside its own PEF raw file format. Adobe’s DNG Converter program provides a solution for those concerned about ‘future-proofing’ their raw files. The software converts proprietary raw files into DNG files, but has the option to embed the original raw data within the files, allowing for its extraction at a later date. This gives the user the advantage of DNG file compatibility, but with the reassurance of keeping the camera’s original file intact. The downside is that embedded DNG files take up more space.

What the camera sees

The greyscale image on the left is the luminance data collected by the camera, before the relevant red, green or blue values are applied to each pixel. Within the raw file is code that tells the software which photosites have red, green or blue filters over them. It then applies a relevant red, green or blue value to the respective pixel, which makes the files look like the red, green and blue representation shown above centre. Finally, the demosaicing and interpolation process creates a recognisable image, with smooth gradients as shown in the final image on the right.

Bit depth

When looking at the specification of a camera, a bit depth figure is normally quoted next to the raw file details. For instance, the Nikon D700 can save raw files at 14-bit or 12-bit. A single ‘bit’ means that a value of either on or off can be recorded – that is, black or white.

When looking at the specification of a camera, a bit depth figure is normally quoted next to the raw file details. For instance, the Nikon D700 can save raw files at 14-bit or 12-bit. A single ‘bit’ means that a value of either on or off can be recorded – that is, black or white.

An 8-bit greyscale image can be made up of 256 different colours – 2 (representing a single bit) to the power of 8 equals 256. In a 14-bit raw file, each colour channel (red, green and blue) can record up to 16,384 different shades. Multiply 16,384 by 16,384 by 16,384 (for each colour channel), and we find that up to 4,398,046,511,104 different colours can be replicated. JPEG files are standardised as 8-bit, so the maximum number of colours they are capable of recording is 16,777,216 (256 to the power of 3).

The histograms on the left show what happens when an 8-bit JPEG file is adjusted in a 16-bit workspace. Whereas the raw file shows a solid block, the JPEG file has a ‘comb’ effect. The gaps in the JPEG histogram occur where there is missing information that would be present in a 16-bit image.

Due to the limitations in the colour reproduction of monitors and printers, differences between bit depths may not always be obvious. However, subtle differences in highlight and shadow detail may be noticeable between 8-bit and 12-, 14- or 16-bit images.

White balance

As well as the image data, raw files also contain the shooting information in the form of Exif data. This information can be used by software to automatically adjust and correct images.

One of the most obvious corrections that takes place is the adjustment of the image’s white balance. By default, a raw file’s white balance is whatever the camera’s white balance was set to, but this can be easily adjusted in software.

It is still possible to adjust the colour of a JPEG image, but care must be taken. As it is only an 8-bit image, any changes should be applied subtly to avoid degradation of image quality.

Image: These examples show it is possible to make slight white balance adjustments to JPEG files, but that more extreme changes can easily be made to raw files

Gamma correction and colour filters

Our eyes and brain perceive light very differently to how it is recorded by a camera sensor. A sensor has linear gamma, which means it has low contrast across the tonal range. Gamma correction, in the form of a contrast curve, is applied to digital images so they are presented as our eyes would have viewed the scene. Data embedded within the raw file contains information about the gamma correction that should be applied. Third-party software developers must work out the level of correction and apply it when converting raw files.

Similarly, the colours of the RGB filters, which are located over each photosite on a camera’s digital sensor, may vary slightly from model to model. This means that certain cameras have better reproduction of particular colours, which gives individual camera models their own colour characteristics. Again, raw conversion software has to interpret these colour values.

Proprietary software usually creates colours that look nearly identical to in-camera JPEGs, while third-party software has to guess at the exact values of these colours.

In comparison, JPEG files have gamma correction and colour filter values applied as part of the in-camera conversion process.

The downside of this is reduced flexibility when editing colours with in-camera settings than in raw conversion software.

The future

Shooting raw files rather than JPEGs allows us to take advantage of future developments in raw conversion. Already some software is better at removing chroma and luminance noise from images than packages from just a few years ago. In the future, there will be even more advances in this area.

By keeping raw images it may be possible to take full advantage of any improvements to ‘redevelop’ images, possibly making them look even better than when they were first taken. However, for anyone who shoots only in JPEG format, the original data from the camera will have been lost, and it won’t be possible to take advantage of improved conversion techniques.

Conclusion

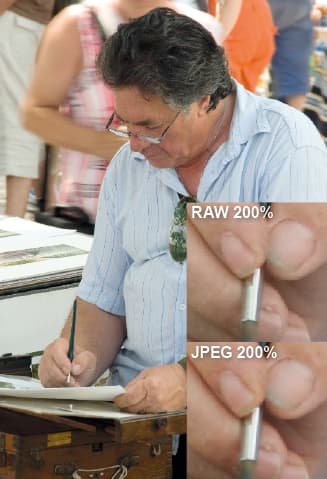

Enlarging a JPEG and a raw file by 200% shows that raw files have slightly better quality, but this will also depend on the camera used

It is clear that raw files offer greater flexibility when it comes to image editing, but whether or not this will make a difference to your images depends on your final intent. If you only ever take snapshots, or images for screen or website use, then shooting raw files is unnecessary.

However, if you need to enlarge images or make extreme corrections, the highest quality will be achieved by using raw files, as they have a far higher tolerance for adjustments.

However, it’s not all negative for the humble JPEG. If you only ever need to make slight corrections, then there isn’t much of an advantage in shooting raw files. After conversion, most raw files end up as JPEGs anyway, so shooting raw files is, on many occasions, unnecessary.

It is also important to know your particular camera and what it is capable of. Different cameras have their own advantages and disadvantages, and knowing exactly how it will perform in a certain situation can help you to make a more educated decision as to which file format to use for which occasion.

By knowing how to use in-camera features to best control noise, sharpening and colour, you may find that JPEG images are enough for most eventualities.

Also consider future use. As raw conversion software improves, so will the quality of images it produces. Archiving raw files allows you to take advantage of this.

With raw conversion and cataloguing programs becoming more prevalent, I’d expect more photographers to shoot in raw format. Of course, if you can’t make up your mind, there is always the option of shooting both at the same time – offering both straight-out-of-camera immediacy and the ability to fine-tune the image to best effect.