Leica M10 Monochrom: at a glance

- £7250 body only

- 40.9MP monochrome full-frame CMOS sensor

- ISO 160-100,000

- Optical viewfinder with rangefinder focusing

- Leica M mount

- 3-in 1.03m-dot touchscreen LCD

Leica is a company that plays by different rules to everyone else. By building cameras in low volumes and charging a premium for them, it’s able to pursue different avenues from the mainstream Japanese makers. It’s maintained a healthy market for its M-series rangefinders, despite this type of camera having generally fallen out of favour in the 1960s, and it also makes cameras dedicated to black & white shooting, with its M Monochrom series.

So how, and why, would you do such a thing? The basic principle is simple: conventional cameras sense colour by arranging red, green and blue filters over the light-sensitive photodiodes of their sensors, with the recorded data being converted to a visually-meaningful photograph through a complex process of demosaicing, noise reduction and sharpening. While this works very well, it delivers less detail and introduces artefacts compared to recording full colour data for each pixel. To produce a black & white image, the colour has to be removed again, but you’re still stuck with the after-effects of the processing. In contrast, by doing without a colour filter array (CFA) over the sensor, the Monochrom cameras are capable of recording black & white images directly. This gives visibly superior tonality and detail, along with higher sensitivity and lower noise.

The latest M10 Monochrom is the third generation of this line, after the original M9-based version from 2012 with its 18MP CCD sensor, and the 2015 follow-up, the Typ 246 with its 24MP CMOS. However while these previous models used existing sensors without a CFA, the latest differs by employing a completely new 40.9-million-pixel full-frame CMOS sensor that doesn’t, as yet, have a conventional colour counterpart. Leica says that this brings a ‘new benchmark in image quality’ to the series. The price tag is eye watering, of course, but in context it’s a premium of just £650 over a standard colour M10-P. Even so, can a camera that costs over £7000, but only shoots in black & white, really make any sense?

Leica M10 Monochrom: Features

To address this question, first we need to think about that new sensor. Not only does it deliver higher resolution than its predecessor, aided by the omission of an optical low-pass filter, it also provides a broader sensitivity range of ISO 160-100,000, compared to ISO 320-25,000. Leica says that it delivers lower noise and increased dynamic range, while being specifically optimised for use with M-mount lenses, which requires a careful arrangement of offset microlenses over the pixels towards the corners of the sensor. Crucially, this means that in principle, the M10 Monochrom should deliver the highest black & white image quality of any current full-frame camera, surpassing what you’d get from colour sensors with higher pixel counts.

The rest of the M10 Monochrom is, however, very basic by modern standards. Being a rangefinder camera, focusing is manual only, with composition via a direct-vision optical viewfinder at the corner of the camera body. You can shoot in either aperture-priority or manual exposure modes, with traditional analogue controls for shutter speed, ISO, aperture and focusing. A simple TTL metering system measures light reflected off the focal-plane shutter, with blades painted in different shades of grey producing a centre-weighted bias.

Timed shutter speeds are available from 8 sec to 1/4000sec in half-stop increments, set using the top-plate dial; with the dial in the B or A positions, this can extend as long as 16 minutes. Continuous shooting is available at 4.5 frames per second, and I was able to rattle off 8 or 9 raw frames in a burst before the camera slowed down (although curiously, Leica promises a 10-shot buffer).

An optical sensor, here appearing blue, reads a 6-bit black-and-white code painted on the lens mount to identify the lens in use

Leica’s venerable M mount dates back to 1954, and as a result is entirely mechanical, with no electronic communication between the camera and lens. But the camera can still identify the lens in use, using an optical sensor to read a set of black or white spots painted onto its mount – a system known as 6-bit coding. This allows the lens ID to be included in the EXIF data, while the focal length can be used to determine the minimum shutter speed when using Auto ISO, if you desire. The camera will still work absolutely fine with non-coded lenses, of course, and with older Leica optics you can specify which one you’re using from a list in the camera’s menu. The camera estimates the aperture used for each shot by comparing the TTL meter reading with that from a lightmeter on the front of the camera, and includes it image EXIF data.

Leica’s design philosophy is to strip the camera back to the essentials, which means it includes only what you really need for stills photography. So you get an exposure bracketing control, a built-in intervalometer, and a 2- or 12-second self-timer, but that’s about it. Notably, like the rest of the M10 series, this is one of the few current models that doesn’t record video.

However the firm isn’t really stuck in the past, and is quite happy to include up-to-date features when they’re genuinely useful. Pressing the LV button on the back enters live view, which enables more accurate focusing and composition than the optical viewfinder, and if you like, the use of adapted manual-focus SLR lenses. It also brings an expanded range of metering options, including multi-pattern and spot. The LCD is touch-sensitive for changing settings and browsing images, and Wi-Fi is built-in for transferring images to your phone using the Leica Fotos app, although Bluetooth is absent.

Leica M10 Monochrom: Focal points

The M10 Monochrom mixes the latest technology with an old-fashioned rangefinder design.

- Leica’s Visoflex (Typ 020) electronic viewfinder can be mounted on the hot shoe. It’s particularly useful when shooting with wideangle, telephoto or macro lenses, and for accurately focusing super-fast lenses

- In a nod to Leica’s 35mm film M cameras, the SD card and battery are accessed by removing the baseplate. The Li-ion BP-SCL5 is charged externally, and should be good for 350-400 shots per charge.

- A mechanical cable release can be screwed into the shutter button. But there are no electronic connectors, such as USB or HDMI ports.

- The M10 Monochrom is based on the M10-P, which means it inherits the same super-quiet shutter

- A series of optical sensors on the lens mount identifies the lens, as long as it has a matched 6-bit code of black and white dots on the mount. The lens name is then included in the EXIF data

- Smartphone connectivity is provided by built-in Wi-Fi, allowing you to copy your favourite images from the camera for sharing

Leica M10 Monochrom: Build and Handling

The Monochrom is based on Leica’s current top-end M10-P rangefinder, and is built like a tank, with a die cast magnesium alloy body shell and brass top and base plates. Everything about it exudes quality, with all the controls operating with satisfying precision. It has the characteristic M-series styling and layout, with curved ends and a stepped top-plate. Compared to its Typ 246 predecessor, it’s 20g lighter and 3.5mm slimmer, which makes it feel surprisingly more svelte. One welcome concession to modern design is the addition of a small thumb ‘hook’ on the back, which provides a nice secure grip.

External controls are kept to the essentials, with analogue dials on the top-plate for shutter speed and ISO, and mechanical aperture and focus rings on the lens. Exposure compensation is applied by pressing a button on the front of the body and spinning an electronic dial on the back. The power switch surrounds the shutter button, and a frameline selector lever is found beneath the viewfinder window. That’s all you generally need to operate the camera.

The ‘digital’ controls are likewise pared down to a minimum, with a d-pad positioned under your thumb, and a column of three large square buttons running down the left side of the LCD. Leica has done a great job of simplifying how these buttons work without restricting access to core functions; for instance in playback, the menu button essentially becomes the delete key. So despite the simplicity, it never really feels as if any buttons are missing.

Meanwhile the touchscreen gives quick access to secondary settings such as metering and drive modes, via an onscreen status display. However you can’t necessarily then change these by touch, which is about the only jarring experience I found when shooting with the camera. The touchscreen also can be used for browsing through your pictures in playback, and checking focus by double-tapping anywhere within an image.

The Monochrom sports a handsome matte black chrome plated finish, with more subdued styling than the M10-P. The lens release and shutter button are finished in black rather than silver, while the A marks on the top-plate dials are painted a muted grey, rather than red. As befits the name, it’s all very monochrome, with the only flash of colour appearing when you lift up the ISO dial to its unlocked position, revealing a slim red surround.

The ISO dial in its raised position, which allows it to be changed. Pushing it back down locks the setting.

The overall result is a camera that’s as beautiful to behold as it is simple and intuitive to use. It really does reduce photography down to the essentials, giving a very different shooting experience to modern auto-everything marvels. It’s absolutely not an all-rounder in the manner of current high-end DSLRs and mirrorless models; instead the manual operation imposes a slower, more considered approach on your photography. Whether this is a good thing or not is purely down to personal preference.

Leica M10 Monochrom: Viewfinder and screen

A always for a rangefinder camera, the M10 Monochrom employs a direct-vision optical viewfinder, meaning that you’re not viewing the image as seen through the lens. Instead, the field of view is indicated using bright framelines in the finder window that are displayed in pairs and selected automatically by the lens: 50mm and 75mm, 35 and 135mm, and 28 and 90mm. They’re parallax-corrected, moving diagonally across the frame as the lens is focused, and in principle indicate 100% of the lens’s the field of view at a focus distance of 2m. At longer distances you’ll get more in the frame, and at closer distances, a little less.

The viewfinder is bright and clear, and at 0.73x magnification, of a very decent size. But you do need to squeeze your eye close to the window to see the 28mm frameline. This means those who wear glasses, or shoot left-eyed, may well struggle; as someone who does both, I found it practically impossible.

Basic exposure information is projected into the viewfinder using red LEDs, including the shutter speed, exposure compensation, and metering indicators when shooting in manual. This works OK, but the display looks incredibly dated compared to the excellent hybrid optical-electronic viewfinder used by Fujifilm in its X-Pro and X100 series cameras.

If you want to shoot with wideangle lenses, you’ll need to use a supplementary viewfinder. You can mount an optical finder on the hot shoe, but the process of switching back and forth between that and the rangefinder makes for a rather awkward shooting experience. The alternative is to switch to live view, but using this on the fixed rear screen isn’t necessarily great either. The best option would be to use the optional Visoflex (Typ 020) electronic viewfinder, which is a 2.36m-dot unit that includes an eye sensor for switching automatically with the LCD. It also includes a GPS unit for geotagging your images, but costs £420.

Leica M10 Monochrom: Focusing

As already mentioned, focusing is manual only, using a coincident-image rangefinder. This approach was popular on film cameras up until the 1970s, and won’t require any explanation for our more experienced readers. But for those unfamiliar with the concept, a second ghost image is overlaid on a bright spot in the centre of the viewfinder, and rotating the focus ring moves it relative to the main view. When the two are aligned, the lens should be correctly focused.

Rangefinder focusing takes a bit of practice, but gives accurate results. Leica APO-Summicron M 1:2/50, 1/125sec at f/2, ISO 1600

Getting used to this method takes a bit of practice. But once mastered, it’s pretty quick and accurate, due in no small part to the fact that Leica’s rangefinder is, by necessity, probably the finest ever made (indeed the complexity and precision of the mechanism is responsible for a significant fraction of the camera’s price). The rangefinder spot is bright and sharply delineated in the viewfinder, and both images are crisp, which makes them easy to align. You just have to be aware that repeating vertical patterns can contribute to incorrect focusing.

Rangefinder focusing does have its limitations. Obviously there’s just a single focus point in the centre of the frame, and when you’re shooting at large apertures, using a focus and recompose technique can result in the kind of small focus errors that we might not have really noticed when shooting with film, but which appear very obvious when examining high-resolution image files onscreen. So it’s best not to move the subject too far off-centre in your composition after focusing, which might explain why so many Leica photographers favour centred subjects.

It’s also important to understand that the accuracy of the focusing is limited by the rangefinder base, which is defined by the distance between the viewfinder and the secondary window on the camera’s front. In practice, this means that it’s not technically possible to focus super-fast lenses consistently to the pixel-level accuracy many photographers now demand. So if you’re contemplating pairing the M10 Monochrom with the £8,600 Noctilux 50mm f/0.95, for example, you’ll only be guaranteed accurate focus if you use live view.

I shot this using an adapted Olympus OM 28mm f/3.5 SLR lens, focused using live view. 1/60sec at f/11, ISO 6400

In this mode, the camera is smart enough to engage a magnified view when it detects the lens being focused, but alternatively you can zoom in manually by pressing the button on the front of the body. The focus area can be moved freely around the frame for use with off-centre subjects, and a focus peaking display is available if you require, in a choice of colours. It’s just worth remembering that the aperture will always be stopped down to what’s set on the lens: this has the advantage of always previewing depth of field, but sometimes it can be better to open it up for focusing.

Leica M10 Monochrom: Performance

Shooting with the M10 Monochrom is a very different proposition to anything else on the market. With its ultra-quiet shutter and understated finish, it’s extremely discreet. Like the rest of the M10 series, it’s about the closest you’ll get to the simplicity of the old-fashioned analogue experience, before the introduction of autofocus and multi-pattern metering. But the Monochrom comes with some unique provisos and quirks that need to be kept in mind, too.

The camera is instantly ready to shoot, the moment you flick the power switch to turn it on. At this point you can choose to work in any way from either fully manual, to aperture priority with Auto ISO. Given that you can set the latter to use either a specific minimum shutter speed, or base it on the focal length of the lens in use (with the option of biasing towards high speeds to minimise any chance of blurring from camera shake), I can see little reason not to use it.

Whichever approach to shooting you take, it’s important to understand the characteristics of the lightmeter. It’s not like modern multi-pattern systems, able to analyse and understand almost any combination of light and shade. Instead, you need to manually adjust it according to the subject, giving an extra stop or two when faced with a bright sky, for example. But equally you have to avoid overexposure whenever possible, because unlike with a colour sensor, there’s no way of reconstructing any lost highlight detail. Instead when it’s clipped to white, it’s gone forever.

The M Monochrom responds to placing coloured filters in front of the lens, in much the same way as black & white film. Yellow, orange and red filters, for example, will progressively darken blue skies and provide additional contrast with any clouds. But they’ll also rob you of light, which potentially means requiring higher ISO settings at the cost of increased image noise. For outdoor shooting in good light, I’d probably use a yellow or orange filter by default.

This comparison shows the difference between using no filter (left) and an orange filter to darken the sky (right)

Naturally, battery life will vary according to how you use the camera. Shooting mostly with the viewfinder, with the occasional foray into live view and image playback, I found 350 to 400 shots per charge to be entirely realistic. But with no USB port, there’s no option to top the battery up in-camera.

Of course the main thing we’re always interested in is image quality, and in a word, it’s sumptuous. In Leica’s hands, all of the theoretical advantages of a monochrome sensor become evidently real. At low ISO the M10 Monochrom is capable of recording a vast amount of detail, with exceptionally low noise and immense dynamic range. There may be no extra highlight detail recoverable in raw processing, but you can delve deep into the shadows with impunity.

At ISO 160 you can make huge adjustments in raw processing, allowing you to expose for the highlights then pull up shadow detail afterwards. Olympus OM 35mm f/2.8 shift, 14sec at f/8, ISO 160

Even when noise becomes plainly visible as the sensitivity is increased, it has an attractive, organic character. As a result, even at higher settings such as ISO 3200, you can still indulge in the kind of extreme image adjustments during raw processing that are usually only workable with colour sensors when shot at their lowest ISOs.

Image files are entirely usable right up to ISO 50,000, which in practice means you can get usable pictures in light so dim that you can barely see to focus and compose. However at the highest settings banding becomes visible in dark evenly-toned regions such as night skies, frequently making ISO 100,000 files unusable.

Leica M10 Monochrom: Image quality tests

Looking at image files from Leica’s 40.9MP monochrome sensor almost requires a suspension of disbelief. The camera can record a phenomenal amount of detail, with higher pixel-level definition and fewer artefacts than we’ve come to accept as normal from colour sensors.

Images are exceptionally clean at ISO 160, and the pure luminance noise recorded at high ISOs is visually unobjectionable. This is a camera that gives fantastic images in bright conditions, while still giving perfectly usable results in vanishingly low light.

Leica M10 Monochrom: Resolution

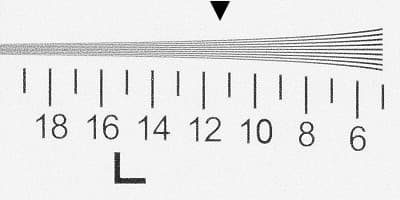

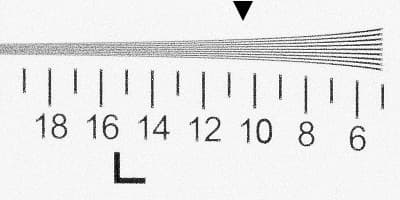

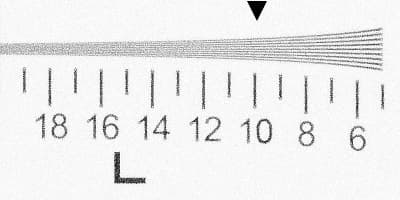

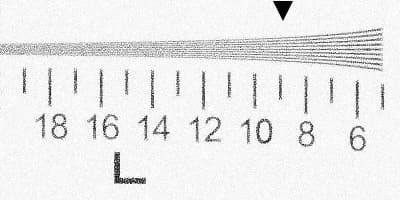

With its 40.9MP sensor, in principle the M10 Monochrom should be able to record close to 5200 lines per picture height. What is extraordinary is how close it comes to achieving this, and just how far you have to raise the sensitivity before the resolution falls. With no colour demosaicing required to develop its raw files, the camera gives an extremely clean rendition of our test pattern at ISO 160, and it’s only at ISO 12,500 that noise obviously reduces resolution, to around 4600 l/ph. Even at ISO 50,000 we register around 4,000 l/ph, which in context is the highest theoretical resolution of the Typ 246.

Looking at the 100% crops below from our resolution chart test, multiply the numbers below the lines by 400 to calculate the resolution in lines per picture height.

Leica M10 Monochrom, DNG + Adobe Camera Raw, Resolution ISO 160

Leica M10 Monochrom, DNG + Adobe Camera Raw, Resolution ISO 6400

Leica M10 Monochrom, DNG + Adobe Camera Raw, Resolution ISO 12,500

Leica M10 Monochrom, DNG + Adobe Camera Raw, Resolution ISO 25,000

Leica M10 Monochrom, DNG + Adobe Camera Raw, Resolution ISO 50,000

Leica M10 Monochrom, DNG + Adobe Camera Raw, Resolution ISO 100,000

Leica M10 Monochrom: ISO and noise

At its lowest ISO 160 setting, the M10 Monochrom captures lots of detail with practically no visible noise. But again, what is remarkable is just how far you can raise the ISO without any significant loss of detail. The ISO 800 image is barely different, and it’s only at ISO 3200 that we start to see a little noise creeping in when viewing at 100% onscreen. But even at ISO 12,500, the M Monochrom is still capable describing the weave of the canvas bag convincingly. By ISO 50,000 noise is swamping fine detail, but the visual effect isn’t remotely objectionable, so I’d happily use this setting when necessary. Not surprisingly ISO 100,000 is probably a step too far, due to the appearance of horizontal banding.

Leica M10 Monochrom, DNG + Adobe Camera Raw, ISO and noise, ISO 160

Leica M10 Monochrom, DNG + Adobe Camera Raw, ISO and noise, ISO 800

Leica M10 Monochrom, DNG + Adobe Camera Raw, ISO and noise, ISO 3200

Leica M10 Monochrom, DNG + Adobe Camera Raw, ISO and noise, ISO 12,500

Leica M10 Monochrom, DNG + Adobe Camera Raw, ISO and noise, ISO 50,000

Leica M10 Monochrom, DNG + Adobe Camera Raw, ISO and noise, ISO 100,000

Leica M10 Monochrom: Verdict

I’ve been lucky enough to spend a week shooting with the Leica M10 Monochrom before its official launch, and there’s no denying that it’s an absolutely beautiful camera. Its build quality is stunning, and the pared-back, minimalist design allows you to immerse yourself completely in the process of taking pictures. Then when you come to look at your image files, it’s immediately obvious that the new sensor is very special indeed. It’s surely a significant enough advance to tempt existing Monochrom users to upgrade.

So to address the question I posed at the start of this review – can a camera that costs over £7000, but only shoots in black & white, really make any sense? Naturally, this is anything but a mainstream product, and for most of us it makes just as much sense as buying a supercar. But for its particular niche, it’s close to perfect. It would be nice to see deeper integration of the touchscreen for changing camera settings, but that’s a minor criticism.

For serious – and well-heeled – photographers who shoot subjects such as street and documentary, at which the M-series excels, the M10 Monochrom is little short of a dream. However black & white photography isn’t limited to these areas, and I’d love to see Leica drop this sensor in the Q2 and SL2 camera bodies too.

More generally, Leica has yet again proven the real value of monochrome sensors. But with this new 40.9MP chip, it’s reached a new pinnacle in black & white image quality: I doubt any other camera on the market can quite match this combination of resolution and low light capability. It’s a real shame the mainstream camera makers don’t share Leica’s imagination in making a mono-only camera.

Looking for more Leica options? Have a look at the best Leica cameras.