DxO PureRAW at a glance:

- £115 (£80 to end of May 2021)

- Raw file ‘pre-converter’

- For Windows and Mac

- Outputs 16-bit linear DNGs

- 30-day free trial available

French software company DxO has a long and distinguished history in digital imaging. It was the first to fully understand and implement the concept of profiled lens aberration corrections with its original Optics Pro software, which it introduced way back in 2004. Since then, the firm has built up a vast database of lens/camera profiles, while the software itself has morphed into a fully-fledged raw converter, DxO PhotoLab. Along the way, DxO has also developed some class-leading demosaicing and noise reduction technologies. In particular, its latest AI-based DeepPRIME denoising, introduced in PhotoLab 4, can lay serious claim to being the best currently available.

However, the firm has also recognised a fundamental reality of the imaging software market. Most people tend to learn a program and stick with it, the Adobe being the 800-pound gorilla in this particular space. No matter how much photographers may grumble about its subscription-only model, the fact remains that a sizeable number of them are locked into using Photoshop and/or Lightroom, because ultimately, they’re incredibly capable industry-standard programs. Other users may have a soft spot for the likes of Serif Affinity Photo or Skylum Luminar. As a result, DxO’s ability to sell PhotoLab is limited by factors other than the quality of its output.

In a stroke of imagination, DxO has come up with a unique solution. Its latest program isn’t a raw converter in the conventional sense, in that it doesn’t output finished image files. Instead, it can be thought of as a pre-converter, which takes the raw data from your camera and applies demosaicing, noise reduction and lens corrections to produce an intermediate DNG file, which aims to represent the purest possible reconstruction of the image that was in front of the camera. This DNG can then be used as a starting point in other programs for the creative side of image development – tonal and colour corrections, pre-sets, LUTs and so on – exactly like a conventional camera raw file.

The idea is that you get the best of both worlds: all of DxO’s image reconstruction expertise, coupled with the familiarity of your preferred software and workflow. It’s a really clever concept, but how well does it work, and is it worth buying?

How to use DxO PureRAW

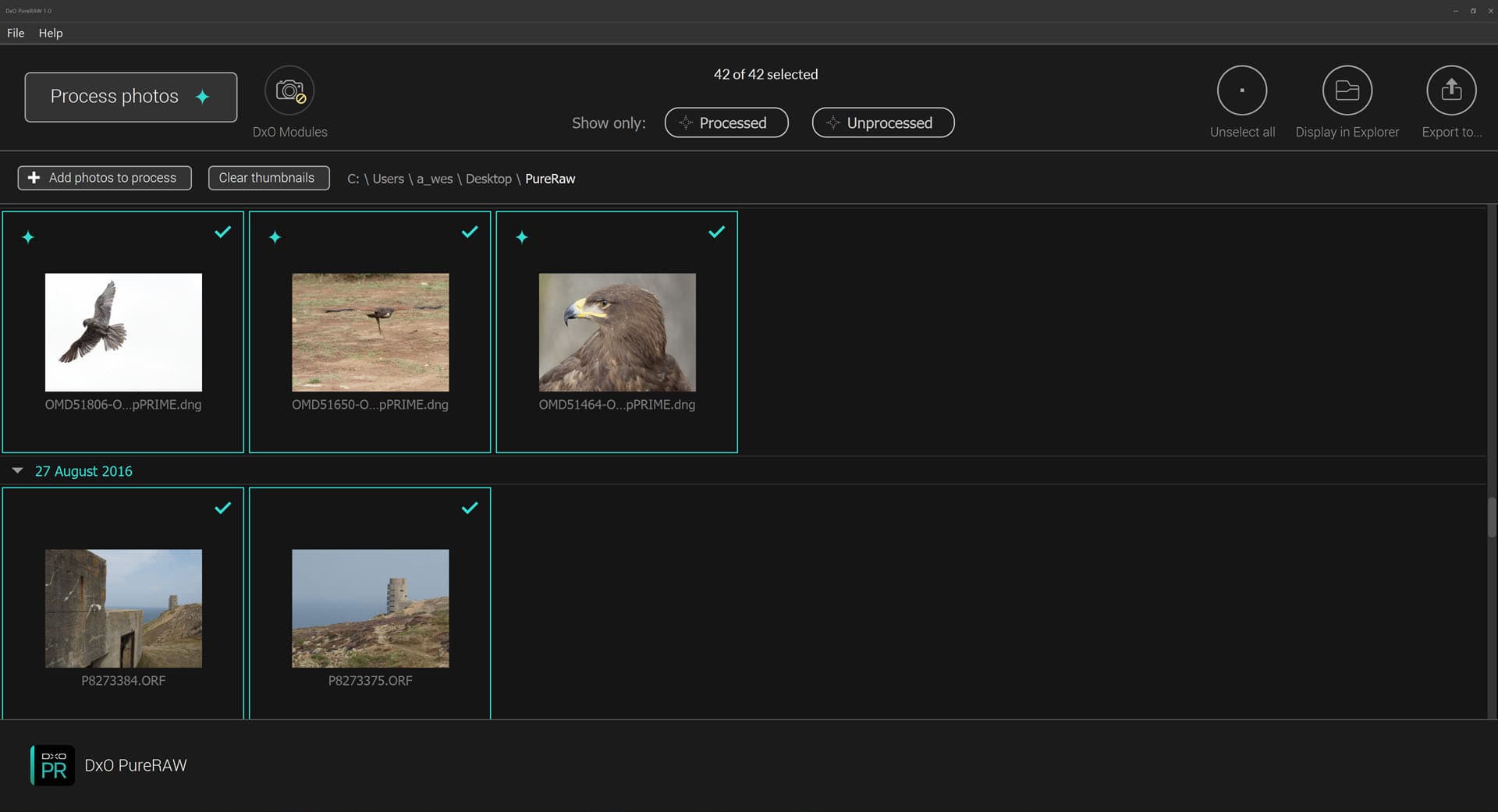

At heart, DxO PureRAW is a pretty simple program. The first time you open it after installation, it provides a brief walk-though of the basic concept. Then you just have to load up raw files that you’d like to convert, which will appear in its main window as thumbnails arranged by the date they were taken. The software will first attempt to identify which camera and lens combination you used for each image, so it can download the requisite correction profiles. It’s important to pay attention here because there can be ambiguities between similar lenses, at which point the software will offer you a choice of profiles. Select the wrong one and you’ll get imperfect results.

The software uses profiled optical corrections, so it’s important to select the right lens when you’re offered a choice

Once the software has downloaded the lens profiles, it’s just a case of selecting the raw files and converting them. The only real control that you’re offered is a choice between three noise reduction algorithms, HQ, PRIME, or DeepPRIME, with the trade-off being processing time against effectiveness. Even if your computer has a modern, powerful processor, DeepPRIME can take almost a minute to chew through a 24MP raw file, so you might prefer to reserve it for use with high ISO files where its benefits are greatest. There’s also the option of converting directly to JPEG rather than DNG, but with no control over colour, white balance, brightness or tonality within PureRAW, it’s difficult to see much point in doing this.

Press the ‘Process photos’ button, and the software will proceed to convert your camera raw files to 16-bit Linear DNGs. By default, they’ll be saved in a DxO sub-folder within their original location, but you can change this if you want. This isn’t quite all the program does, though. Once the files are converted, PureRAW can display a split screen before-and-after view, showing you how much improvement it’s made to the original file.

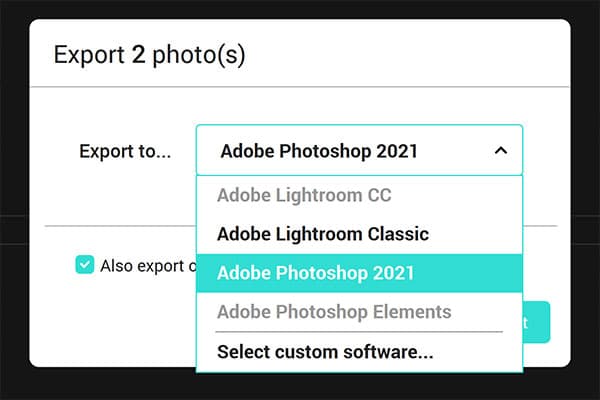

PureRAW can export processed DNG files directly to your preferred raw converter

Most usefully, the software can also send its DNGs to external software such as Lightroom or Photoshop for development; if you select the latter, they’ll open in Adobe Camera Raw. Even better, it can send the original raw file alongside, which allows you to copy its development settings to the new re-processed version and compare the two. So if you’ve previously spent time working on the original raw file, you don’t have to replicate that effort all over again. However, you may still need to make a few additional tweaks to get the PureRAW version to match your previous processing perfectly.

Is DxO PureRAW worth using?

To establish what benefits you might gain from using PureRAW, I tested it with a wide range of raw files from cameras both new and old, with both affordable and premium lenses, and across a full range of sensor sizes. By considering what the program claims to do, though, it’s easy enough to predict when it should be most beneficial.

PureRAW offers significant benefits with high-ISO files, significantly suppressing noise without smearing details. Olympus OM-D E-M1 Mark II, 40-150mm f/2.8 at 150mm, 1/8000sec at f/4, ISO 3200

If your raw files are already technically excellent – in other words, shot on a modern full-frame sensor at low ISO, with top notch lenses and perfectly controlled lighting – it’s unlikely to buy you much advantage. If on the other hand you have files that were shot at high ISOs, using relatively inexpensive lenses, with smaller-sensor systems or simply old camera models, then you potentially have much more to gain.

What certainly surprised me, though, is just how significant the improvements can be. To illustrate this, let’s look at some examples of how the output from PureRAW compares to that produced by Adobe Camera Raw.

DxO PureRAW example one – Noise reduction

Firstly, let’s examine an image I took using the Canon PowerShot G3 X, a bridge camera with a 1-inch sensor and a 24-600mm equivalent lens. One of my favourite pictures from this camera was of a neighbourhood cat perched on a brick wall, staring at me disapprovingly against a lovely soft blurred background. It’s shot at 600mm equivalent, where the lens is weakest, and ISO 1000, which is visibly noisy.

Canon PowerShot G3 X, 600mm equivalent, 1/320sec at f/5.6, ISO 1000. Processed using PureRAW then Adobe Camera Raw

DxO PureRAW version, 100% crop

The PureRAW version is vastly better than Adobe’s effort, retaining much more detail in the cat’s fur, while smoothing away all traces of noise in the bokeh. This is fundamentally what DeepPRIME is designed to do, and it certainly delivers the goods, effectively making the image look like it was shot at a lower ISO. There’s still a degree of ‘waxiness’ if you look at the background closely onscreen, but this shouldn’t be a problem in print.

DxO PureRAW example two – Dynamic range

Second is a related concept, but instead of mid-tone noise, we’re concerned about the type of shadow noise that can become troublesome when making significant tonal adjustments in raw processing. I shot this image using my Olympus OM-D E-M5 Mark II, exposing to retain highlight detail in the illuminated buildings in the pre-dawn light, and using ISO 400 to keep the shutter speed high enough to hand-hold. Little detail in the gorge is visible in the original JPEG; instead I’ve pulled it up using exposure and shadow adjustments in raw processing.

Olympus OM-D E-M5 Mark II, 7-14mm f/2.8 at 7mm, 0.6sec at f/2.8, ISO 400. Processed in DxO PureRAW then Adobe Camera Raw

DxO PureRAW version, 100% crop

In the Adobe version there’s a fair amount of blotchy colour noise visible, but DeepPRIME suppresses it without any loss of detail. In effect, DxO’s processing has extended the raw file’s usable dynamic range, counteracting one of the perceived weaknesses of smaller sensors.

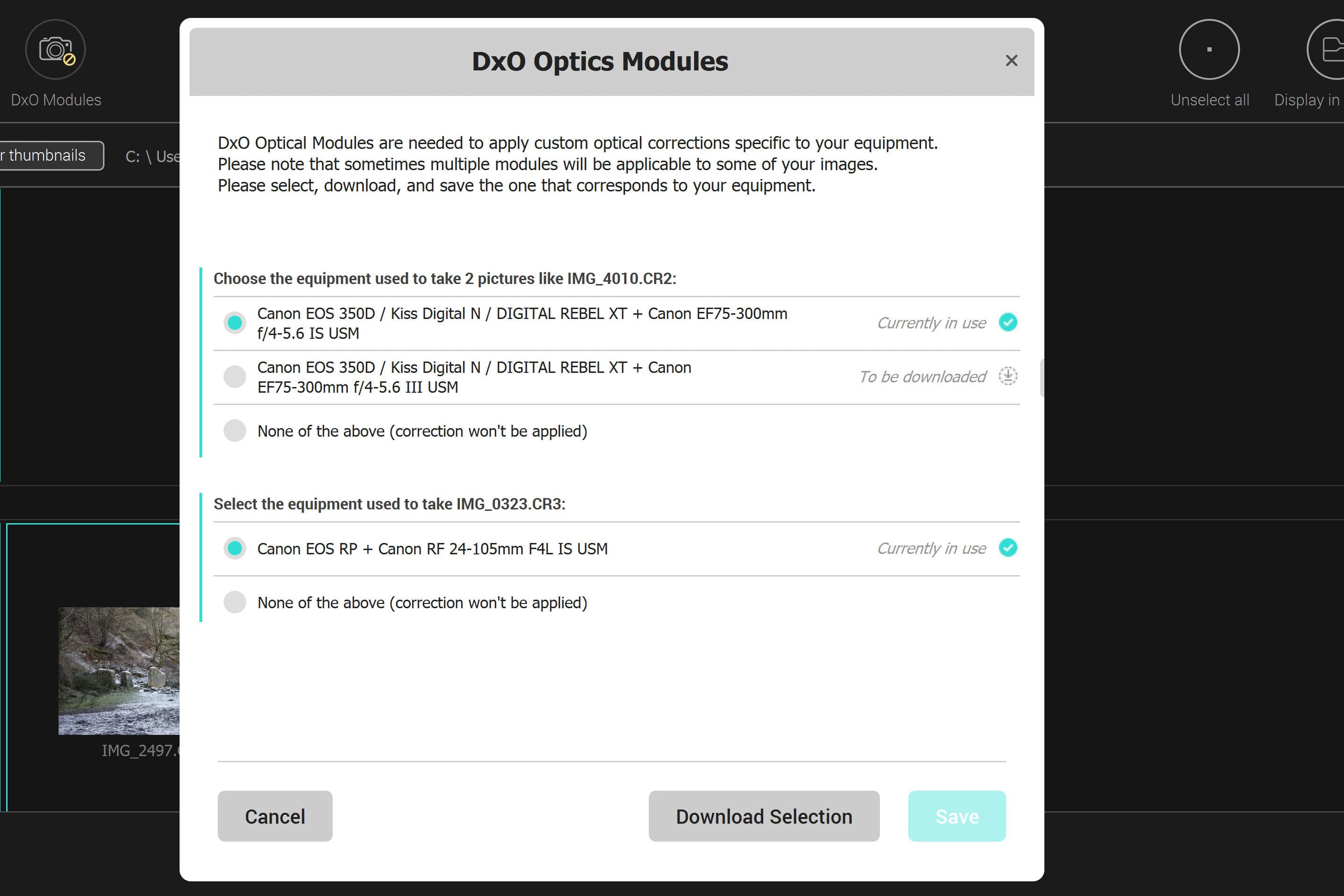

DxO PureRAW example three – Old camera, soft lens

This comparison illustrates DxO’s other main area of expertise – that of lens corrections. I took this photo in 2005 using an 8MP Canon EOS 350D, coupled with the decade-older Canon EF 75-300mm f/4-5.6 IS USM. This was the world’s first image-stabilised SLR lens, and it wasn’t very sharp, especially at 300mm f/5.6 as used here. Incidentally this is also an example where DxO couldn’t unambiguously identify the lens from the file’s EXIF data, so I had to manually select the profile for the stabilised version.

Canon EOS 350D + Canon EF 75-300mm f/4-5.6 IS USM at 300mm. 1/250sec at f/5.6, ISO 100. Processed in DxO PureRAW then Adobe Camera Raw

100% crop, DxO PureRAW version

What PureRAW has achieved with this file is impressive, teasing out texture in the elephant’s hide that’s barely visible in the Adobe version. As a result, it’s done a fine job of reviving an old, relatively poor-quality file to something that I’d now happily print rather larger than before. I’m not going to pretend that the results are as good as if I’d used a modern lens and camera, but that’s really not the point.

DxO PureRAW example four – High-quality file

Finally, let’s look at an example where you’d probably assume PureRAW can’t provide so much in the way of improvement. This picture is of a professionally made-up model at Leica’s launch event for the full-frame 24MP full-frame SL, photographed using the SL 24-90mm f/2.8-4 ASPH zoom, a no-compromise optic that costs over £4000. It’s taken at f/5.6, which is perhaps the lens’s sharpest aperture, using studio flash.

Leica SL, 28-90mm f/2.8-4 at 90mm, 1/250sec at f/5.6, ISO 100. Processed in DxO PureRAW then Adobe Camera RAW

DxO PureRAW version, 100% crop

Technically, the raw file is practically flawless, and it’s difficult to pick much argument with Adobe’s rendition. However, the PureRAW version is visibly much sharper. Whether this is what you want with portraits is an entirely different matter.

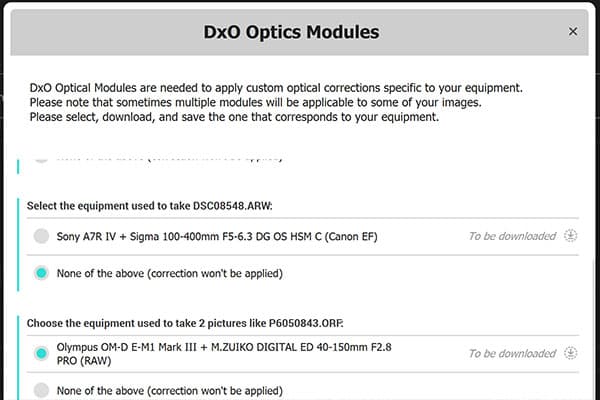

DxO PureRAW camera and lens support

While DxO PureRAW works with a vast range of cameras and lenses, there are a few exceptions. The most glaring and unfortunate is that the firm has never supported Fujifilm’s X-Trans colour filter array, so users of the excellent APS-C X-system cameras will have to live without it. Some very old raw files might not work either; for example, I was unable to persuade it to recognise Canon’s original CRW format from the early 2000s.

DxO didn’t offer a profile for the never Sigma 100-400mm f/5-6.3 DG DN OS telezoom

At the other end of the scale, DxO can take a little while to add the latest lenses to its database; at the time of writing there’s no profile for the 10-month-old Sigma 100-400mm F5-6.3 DG DN OS.

Our verdict

With the release of PureRAW, DxO has thrown us something of a curve ball. We haven’t seen anything quite like this before, and it might be difficult for prospective users to see the point in spending a substantial sum of money on a program that converts camera raw files to DNGs. But the proof of the pudding is in the eating, and if you’re a dyed-in-the-wool Adobe user, PureRAW can usefully expand the scope of what you can do with your files, particularly those shot at high ISOs or with less-than-perfect lenses.

It’s not just small sensors that can benefit from PureRAW. Here it allowed me to pull up the balloon’s canopy without it being swamped by noise. Canon EOS RP, RF 24-105mm F4L IS USM at 35mm, 1/100sec at f/8, ISO 100

In this review I’ve deliberately selected examples that nicely illustrate PureRAW’s potential to give improved results with technically compromised raw files, but each user will get different benefits, depending on the kit they use and how they shoot. Thankfully DxO offers a 30-day free trial, so you can download and try it for yourself. Personally, I can see PureRAW becoming an important component of my image-processing toolkit.