Zeiss Milvus Distagon 25mm f/1.4 Review

Two years ago, Zeiss introduced the photographic world to its Milvus range of manual-focus prime lenses. Designed for use on DSLRs with high-resolution full-frame sensors, they have a common set of features, with Zeiss promising best-in-class optical performance, weather-sealed construction, and colour-matched images throughout the range. We were hugely impressed by the first models, including stellar new 50mm f/1.4 and 85mm f/1.4 optics, and since then Zeiss has fleshed-out the line to cover focal lengths from 15mm to 135mm.

Its latest in the series is the Milvus Distagon T* 25mm f/1.4, which offers a classic wideangle view on full-frame DSLRs. It’s available in two mounts: ZE for Canon EOS, and ZF for Nikon SLRs. But with its £1,999 price tag it will have its work cut out in the market, as it will be competing directly against some very highly-regarded optics: namely the Canon EF 24mm f/1.4L II USM and Nikon AF-S Nikkor 24mm f/1.4G ED which both cost in the region of £1500, and the £650 Sigma 24mm f/1.4 DG HSM Art. With these lenses all offering autofocus too, who in their right mind might buy the manual-focus Milvus, and why?

Zeiss Milvus 25mm f/1.4 – Features

One clue to the lens’s possible attraction comes from its optical formula. With 15 elements in 13 groups, it’s more complex than its Canon and Nikon equivalents, and all these elements potentially allow better correction of optical aberrations. The Distagon name has been used by Zeiss since 1952, and denotes a wideangle lens that’s placed a large distance from the imager, as demanded by the mirror box of DSLRs. Such lenses demand an array of special elements and glass types to keep aberrations in check, and as a result Zeiss has employed two aspherical elements and no fewer than seven made from anomalous partial dispersion glass in the optical design. Lens elements are also treated with Zeiss’s T* coating to minimize flare and ghosting, which Zeiss says helps to make the most of the huge dynamic range of modern digital sensors.

Zeiss has used an aperture diaphragm with nine rounded blades, in a bid to render out-of-focus backgrounds with an attractive blur; it will also give 18-ray sun stars when stopped down towards its minimum of setting of f/16. The Nikon-mount version that I tested even includes a good old-fashioned mechanical aperture ring, allowing back-compatibility with Nikon’s manual-focus film SLRs. This clicks at half-stop intervals, although the camera only detects and displays full stops in the viewfinder. A small button that’s perfectly placed beneath your thumb locks the ring at f/16 for use on cameras that don’t support lenses with manual aperture rings, or for when you prefer to use the electronic command dial on the body. Videographers will be pleased to hear that the aperture ring can be de-clicked by rotating a small screw that’s embedded in the mount through 180 degrees, using a tool that’s supplied in the box.

The minimum focus distance is 25cm, which is pretty typical for this class of lens, with a floating focus system employed to maximize image quality throughout the distance range. Focusing is fully internal (in other words, the front element doesn’t move back or forwards), meaning that the 82mm filter thread doesn’t rotate during the process.

Zeiss Milvus 25mm f/1.4 – Build and handling

It’s clear from the moment you first open the box that this is one big, heavy beast of a lens. Indeed at 114mm long and 95mm in diameter, it’s substantially larger than its autofocus equivalents, while its near-1.1 kg weight counts as half as much again. Like the rest of the Milvus range, the 25mm is sealed against dust and moisture, with the most visible sign of this being a blue rubber seal around the metal lens mount.

The lens’s all-metal construction and modern-looking, minimalist design simply exudes quality: even the hood is an object of beauty, with its sculpted curves blending seamlessly into the lines of the barrel. The hood clicks satisfyingly into place, and its deep petal-type design and felt lining mean it should be effective at blocking stray light, too. It can be mounted backwards to save space when the lens isn’t in use, too.

The smooth rubber focus ring gives pretty good grip, and includes a traditional distance and depth-of-field scale along with an adjustment mark for use with infrared film. On my review sample, the infinity mark was perfectly calibrated, but the focus ring can turn a little way beyond to deal with varying ambient temperatures. It takes almost half a turn to adjust between infinity and the minimum object distance of 25cm, which allows exceptionally precise adjustment. The DoF scale is calibrated for making prints, by the way, so don’t expect it to be a predictor of pixel-level sharpness when examining your images up-close onscreen.

I tested the lens on the Nikon D810, which like the firm’s other professional DSLRs allows you to choose between setting the aperture using either the camera’s electronic command dials, or the ring on the lens itself. If you prefer the latter approach, you’ll quickly find that due to the lens’s bulky barrel, access to the aperture ring is quite restricted, with not a huge amount of room for your fingers. This didn’t bother me much in practice, but might irritate users with large hands. The half-stop click points are quite distinct, but a little loose compared to many classic manual-focus primes of the past.

Another quirk of the lens’s design is that the entire metal front section of the barrel behind the hood mount rotates along with the smooth rubber focus ring. I’m not wholly convinced by this design; it makes it oddly difficult to get the lens on or off the camera, as there’s barely any non-rotating section of the barrel left to grasp; Zeiss suggests you should be using the small indents on the sides of the lens close to the camera. Of rather more concern, I also found it was too easy to nudge the focus slightly when I didn’t really want to, simply because this forward metal section is the best place to support the lens when you’re shooting. So even a slight adjustment of your grip can move the focus ring a little. Unfortunately at f/1.4 this can be the difference between your subject being perfectly in-focus or not.

Zeiss Milvus Distagon 25mm f/1.4 – Focusing

If you’re considering buying this big chunky expensive lens, it’s presumably for Zeiss’s famed optical quality. This means that you’ll probably want to get your subjects in absolutely perfect focus when shooting at large apertures – otherwise, you simply won’t achieve the results that it’s capable of.

Accurate focusing is critical to get the most from the lens. Sony Alpha 7 II, 1/5000sec f/1.4, ISO100

This, however, is where problems arise. It’s a dirty secret of autofocus SLRs that their focus screens simply aren’t suitable for really precise manual focus with fast primes; this is a direct consequence of them also having to be suitable for use with relatively slow maximum aperture zooms, compounded by the fact that a significant fraction of the light gathered by the lens is diverted away from the viewfinder to the autofocus sensor. With many older DSLRs it’s possible to change the focus screen to one that provides a better visual ‘snap’ for more accurate focusing, but in return gives a dark view when used with lenses of f/4 or slower. Unfortunately though, interchangeable screens are becoming increasingly rare with the demand for switchable information overlays and gridlines.

This image is slightly misfocused, despite the camera indicating it was correctly focused. Nikon D810, 1/50sec f/2, ISO1250

Just as I feared, when I tested how best to attain correct focus, I found that the focus snap in the D810’s viewfinder isn’t all that great, and certainly insufficient for obtaining perfectly sharp pictures when shooting at f/1.4. Help is at hand, though, in the shape of Nikon’s virtual rangefinder, which uses the autofocus sensor to judge when the image is properly sharp. This gives better results than relying on the focus screen, but still has too much leeway to guarantee perfectly sharp images. For truly accurate focusing at large apertures, you really have to use magnified live view – but realistically this demands using a tripod. I got much better results hand-held by switching to using the lens on a Sony Alpha 7 II via a mount adapter.

Zeiss Milvus Distagon 25mm f/1.4 – Performance

So the Zeiss 25mm f/1.4 is huge, heavy, and extremely difficult to focus accurately enough to get perfectly sharp images. But when you do get your shots in focus, the reason for its size and price become clear – it’s a very impressive performer, resolving fine details right across the frame. There’s some smearing of fine detail in the extreme corners at maximum aperture, of course, but an impressively low degree, and you don’t have to move far into the frame for details to sharpen right up. Stop down to f/5.6 and even those corners become pretty much as sharp as you could reasonably want.

Indeed most aberrations are all-but eliminated: there’s a tiny bit of colour fringing in the corners of the image as a result of lateral chromatic aberration, but it’s only visible if you really go hunting for it, even with unforgiving high-resolution sensors. Likewise I struggled to find any sign of longitudinal chromatic aberration at all, so you won’t see any troublesome colour fringing in out-of-focus areas that’s so difficult to correct in post-processing. There’s a small degree of barrel distortion, but it’s really not going to be a problem unless you shoot symmetric, geometric images, and even then it’s a simple fix. Overall the lens’s most obvious ‘flaw’ is vignetting at large apertures – but you’re always going to see that from a full-frame fast prime.

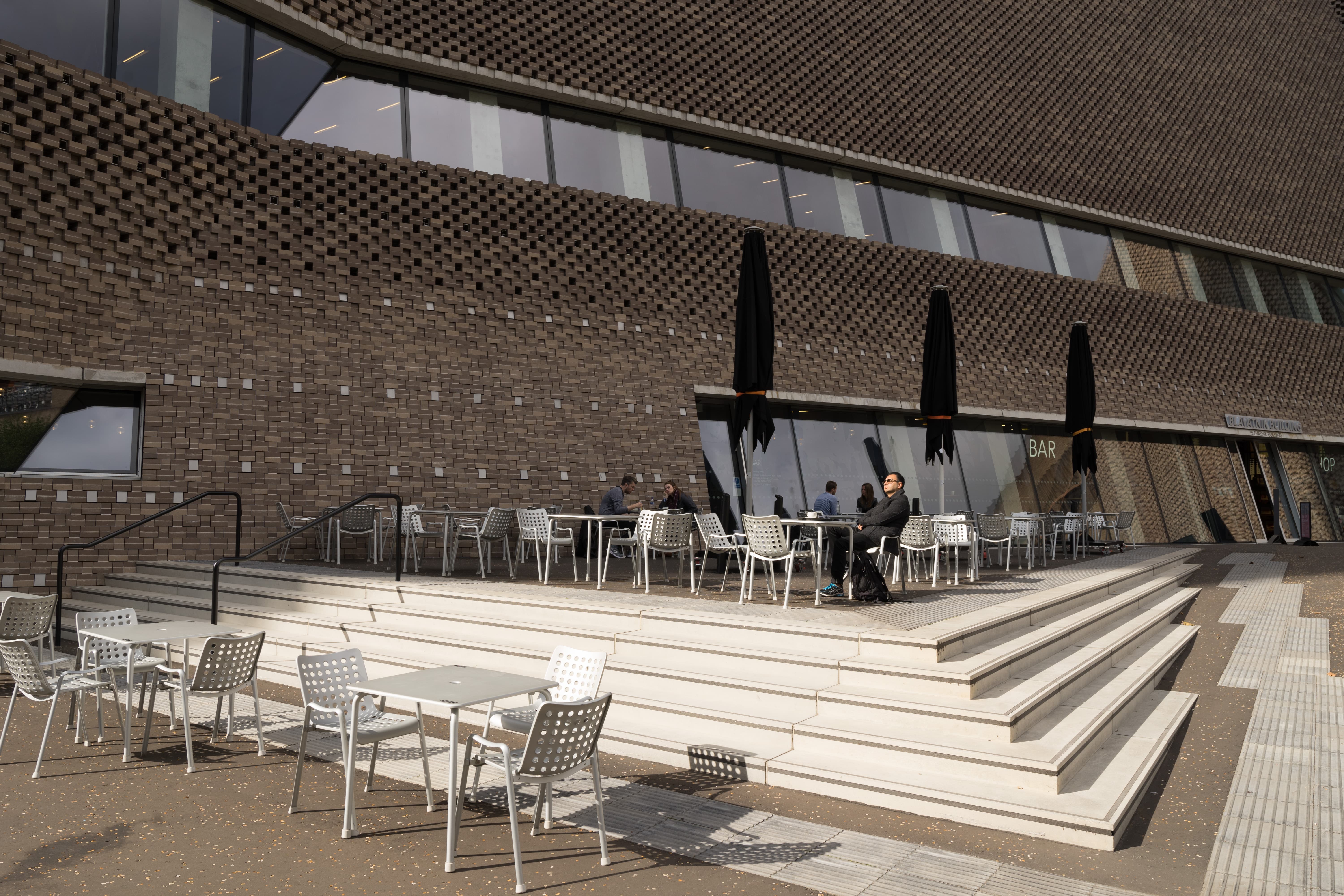

Stop down and the lens renders loads of detail all across the frame. Sony Alpha 7 II, 1/125sec f/11 ISO100

As a result, images from the Milvus 25mm f/1.4 are incredibly sharp, clean and detailed, almost regardless of what aperture you choose to work at. This means that it’s a great lens for low-light work; not only can you realistically shoot at f/1.4 when necessary, you can also stop down and raise the ISO further than you might otherwise dare, safe in the knowledge that the lens is providing the kind of crisp fine detail that is less likely to be smeared away by noise-reduction algorithms.

Out-of-focus highlights are rendered with slightly bright edges. Sony Alpha 7 II, 1/125sec f/1.4, ISO 100

If I have any criticism at all, it’s that out-of-focus backgrounds can be a little harsh, with noticeable bright rings around highlight blur discs. But that’s not really surprising from a fast wideangle. On a more positive note flare is very well controlled, and the lens gives attractive 18-point sunstars when shooting into the light stopped-down.

Zeiss Milvus Distagon 25mm f/1.4 – Resolution

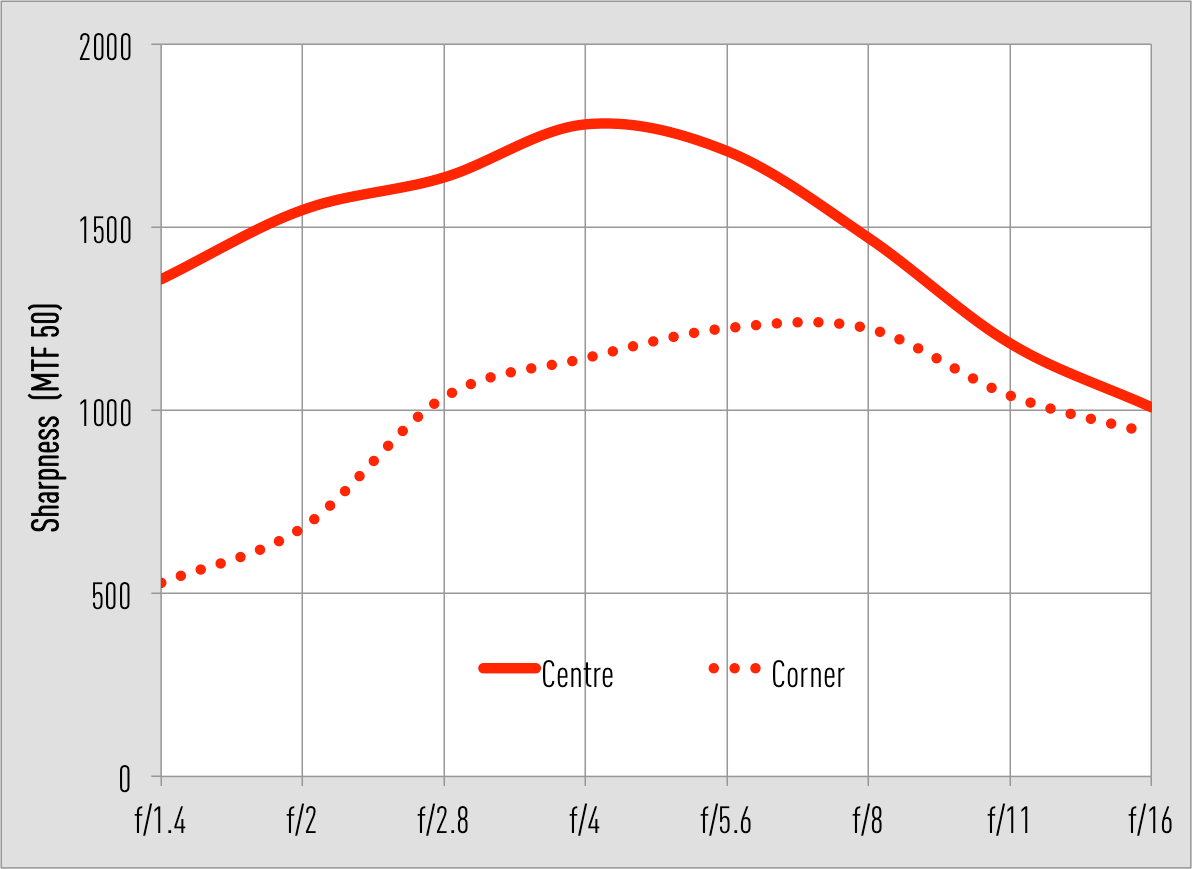

Tested on the 45MP Nikon D850, the Milvus 25mm f/1.4 delivers an excellent set of results in our Image Engineering MTF50 tests. It’s spectacularly sharp in the frame centre even at f/1.4, and only gets better on stopping down. The corners register rather lower values, but examination of real-world images reveals that the lens can still resolve very fine detail, just at low contrast. The optimum apertures to attain the best cross-frame sharpness are f/5.6 to f/8, but you’ll often need to stop down further for depth of field.

Zeiss Milvus Distagon T* 25mm f/1.4 MTF50, tested on Nikon D850

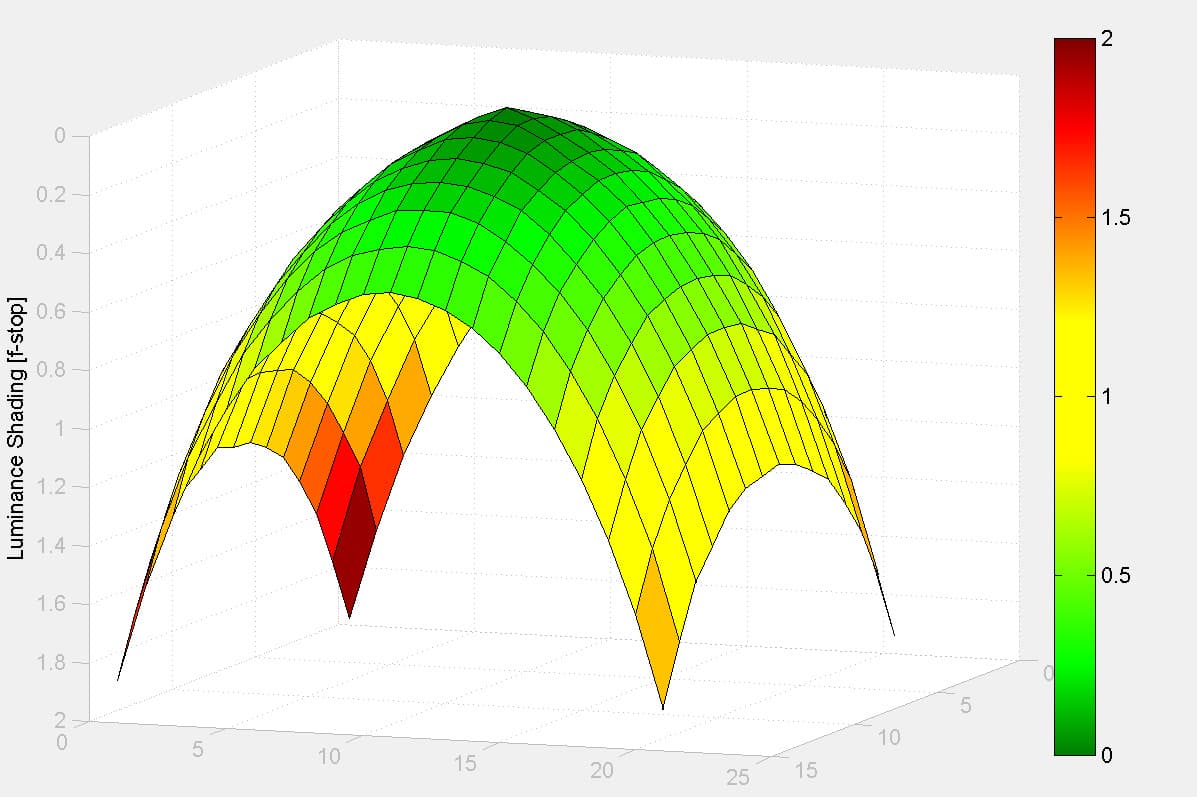

Zeiss Milvus Distagon 25mm f/1.4 – Shading

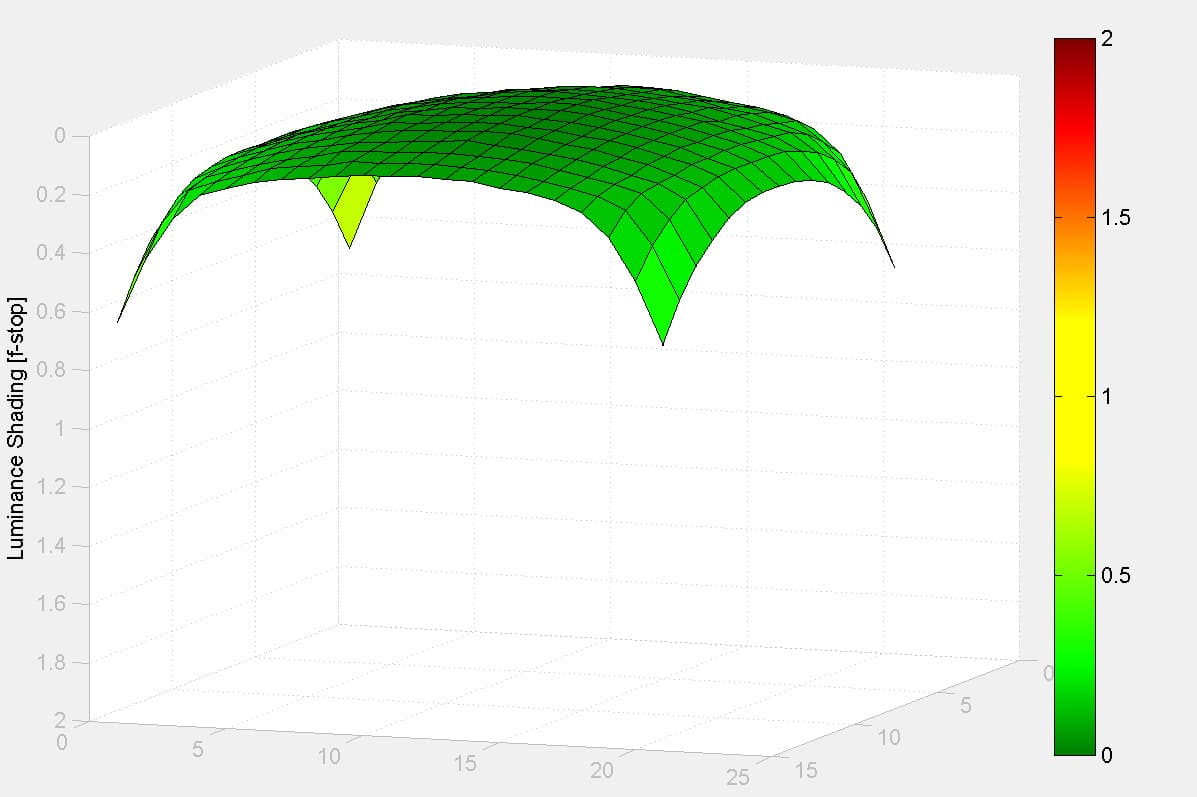

Just as we’d expect for a fast prime on full-frame, the Milvus 25mm displays considerable shading wide open, with an almost 2-stop drop in illumination at the image corners when set to f/1.4. Stopping down to f/2 reduces this considerably to 1.2 stops, and by f/2.8 only slight darkening is detectable in the extreme corners of the frame.

Zeiss Milvus Distagon T* 25mm f/1.4 shading at f/1.4

Zeiss Milvus Distagon T* 25mm f/1.4 shading at f/2.8

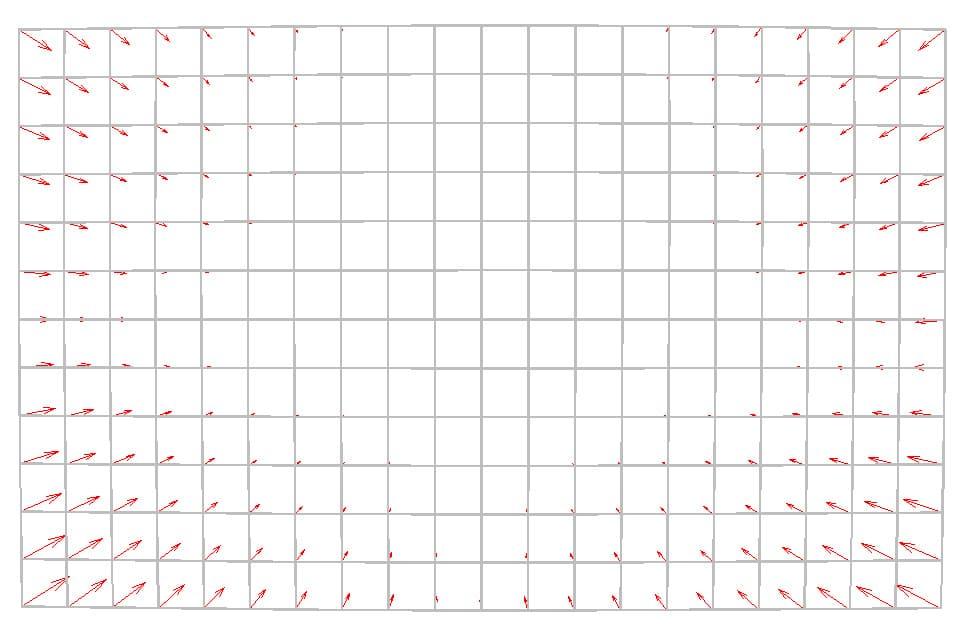

Zeiss Milvus Distagon 25mm f/1.4 – Curvilinear Distortion

As is typical of wideangle lenses, a little barrel distortion is visible in our test chart shots, but it’s not especially strong. It’s also very simple in character, which means it’s easy enough to fix in software without even having to resort to profiled lens corrections. I found that applying a setting of +10 in Adobe Camera Raw gave near-perfect compensation.

Zeiss Milvus Distagon T* 25mm f/1.4 Distortion. Barrel-type, SMIA TV = -1.2%

Zeiss Milvus Distagon 25mm f/1.4 – Verdict

Lenses like the Zeiss Milvus Distagon T* 25mm f/1.4 are always going to polarise opinion. For some photographers, for instance those who shoot landscapes or architecture, the ability to call upon optics of such high quality is worth the size and price premium over more mainstream alternatives. Couple this lens with a high-resolution DSLR like the Nikon D850 or Canon EOS 5DS R and you’ll be able to make huge prints that are jam-packed full of detail, with the minimum of effort in post-processing.

However, for most photographers, it’s just not that practical. Super-sharp manual-focus fast primes for DSLR face an almost existential problem: what’s the point when the camera itself makes it near-impossible to focus them accurately enough to get truly sharp images when shooting at large apertures using the viewfinder? Most users will probably prefer the experience of shooting with the autofocus Canon, Nikon or Sigma 24mm f/1.4 lenses instead.

With its large aperture and wideangle view, the lens is great for shooting interiors. Sony Alpha 7 II, 1.8sec at f/1.4, ISO 200

But that’s the point really; Zeiss lenses are for the kind of seriously committed photographer who really understands their advantages and limitations, and knows how to get the most out of them. For that sort of user, the Milvus 25mm f/1.4 is a genuinely superb choice.