Introduction

When Sony first showed an array of new FE lenses to fit its Alpha 7 series of full-frame compact system cameras in January, our attention was perhaps understandably drawn to the big guns – particularly, the fast 35mm f/1.4 and the 90mm f/2.8 macro.

In comparison, the more modest FE 28mm f/2 wideangle optic slipped slightly under the radar – even with its dedicated bayonet-mount ultra-wide and fisheye converters. But after a couple of weeks shooting with it, I’ve come to the conclusion that it’s worthy of rather more serious consideration.

At around £400, the 28mm f/2 is the least expensive FE lens. Sony calls it an excellent choice as a second lens to supplement a kit zoom, but I’m not quite so sure – personally, I’d suggest the 55mm f/1.8 as a better general-purpose option. Instead, as a fairly fast wideangle prime, it’s an interesting choice for low-light shooting of landscapes, interiors and the like.

The 28mm f/2 (left) with the fisheye (centre) and ultra wide converter (right)

More interestingly, with its matched converters the 28mm becomes three lenses in one. Add the £220 (SEL075UWC) Ultra Wide Converter and you get a 21mm f/2.8, and with the £280 (SEL057FEC) Fisheye converter you get a 16mm f/3.5 fisheye with a 180° diagonal angle of view.

In effect, you get three lenses for the same price as the FE 24-70mm f/4 OSS zoom alone. We’ll examine the converters in detail later in this article, but for now let’s take a closer look at the 28mm f/2 prime lens.

Features

With its small barrel and 49mm filter thread, the 28mm f/2 doesn’t feel oversized

It may be a plain-looking lens on the outside, but the 28mm optic doesn’t skimp when it comes to the optics. The nine-element, eight-group design includes two ED glass elements, two aspheric elements and an advanced aspheric element to suppress distortion and chromatic aberration. Unusually for a full-frame 28mm, it uses an approximately symmetric optical formula, which should also help minimise any optical flaws.

An internal focus design is employed, with a silent linear stepper motor to drive the focus group. As with other FE lenses, manual focus is electronically driven, and the focus ring has no end-stops to its movement. At the lens’s minimum focus distance of 29cm, a maximum magnification of 0.13x is achieved. It’s worth noting that there’s no optical image stabilisation.

Nine curved blades make up the aperture diaphragm, which is capable of stopping down to f/22 in 1/3-stop increments. Filters can be attached to the lens via a 49mm thread that does not rotate on focusing, which should be welcomed by users of polarisers and grads. The bayonet mount accepts the supplied petal-shaped plastic hood, as well as the two converter lenses.

The 28mm is designated an FE lens for full frame, but with a standard E-mount it will also fit onto Sony’s APS-C-sensor compact system cameras. On these it will give a 42mm (equivalent) angle of view, making it an attractive option as a fast normal prime that offers a very natural perspective to images. It is therefore a particularly attractive option for anyone using both formats side-by-side.

Build and Handling

The 28mm makes for a well-balanced combination on A7-series bodies

Measuring 64mm in diameter and 60mm long, the 28mm is one of Sony’s smallest FE lenses, second only to the 35mm f/2.8 ZA. I find it is especially well matched to the compact Alpha 7 bodies, and at 200g it adds little to the overall weight.

This makes it considerably more portable than similar-spec DSLR lenses like Nikon’s recent 28mm f/1.8G, which measures 73 x 81mm and weighs 330g – a direct advantage of the smaller back-focus distance afforded by the mirrorless E mount.

The lens barrel is made of aluminium alloy, and feels robust despite its light weight. Sony says the lens is resistant to dust and moisture, which makes it a good companion to the Alpha 7 models for landscape shooters. The only external control is the finely ridged and smoothly rotating focus ring.

Autofocus

Driven by a linear stepper motor, autofocus is almost completely inaudible during both stills and movie use. When used on the Alpha 7 and 7R autofocus is reasonably quick – not breathtakingly fast as on some other compact system cameras, but it’s not obviously slow either.

As we’d expect from an on-sensor AF system, accuracy is excellent even when shooting at f/2 – none of the 300 or so real-world shots I took with the lens was remotely out of focus.

Image Quality

I tested the Sony FE 28mm f/2 lens predominantly on the 24.3-million-pixel Alpha 7, and found that it delivers consistently good-looking images. It’s pretty sharp wide open, although there’s a noticeable drop-off in crispness towards the edges and corners of the frame.

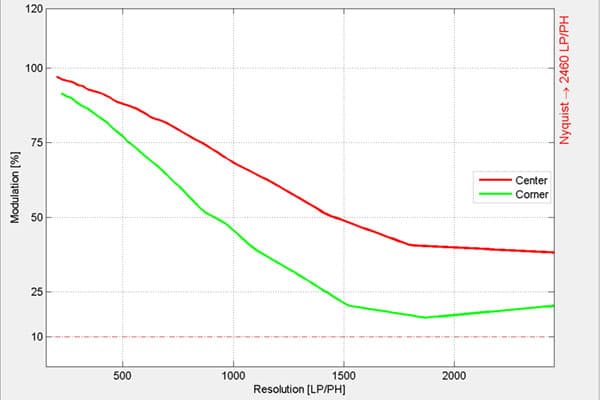

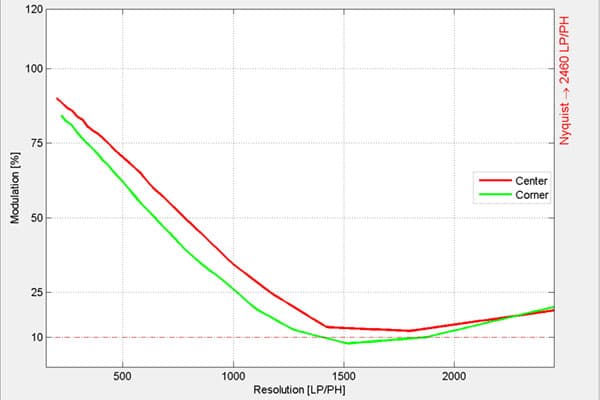

These improve quickly on stopping down, and even for landscapes with lots of corner-to-corner detail I’d be perfectly happy shooting at f/5.6. On full frame, of course, you’ll likely want to stop down at least this far, and more likely to f/8 or f/11, to achieve sufficient depth of field.

When it comes to assessing other aspects of the lens’s image quality, we first have to understand how this lens is designed. Like almost all modern CSC designs, the Sony FE 28mm f/2 is based around a combination of optical and software corrections. Sony considers distortion correction to be obligatory, meaning you can’t turn it off in-camera. Because of this, images shot with this lens show no visible curvilinear distortion in normal use – straight lines along the edges of the frame are rendered correctly. However while raw files will be automatically corrected by Sony’s own software, this isn’t the case with third-party programs such as Lightroom or Adobe Camera Raw. Here you’ll probably want to use profiled lens corrections, especially for subjects with straight lines such as architecture.

Meanwhile, vignetting and lateral chromatic aberration are also corrected in-camera by default. However, if you happen to like colour fringing and dark corners, you can choose to turn these corrections off.

Turn off shading compensation, though, and you’ll see very noticeable corner darkening wide open, which is still quite strong at f/2.8 and never fully goes away. Normally, I don’t mind a bit of vignetting, but on this lens it’s sufficiently strong that it can detract from the image.

If I were shooting predominantly in JPEG format, I’d leave in-camera compensation turned on, which clears it up completely. However, if I were shooting raw I’d probably turn the menu setting off and correct in post-processing.

When it comes to chromatic aberration, the lens shows visible red/cyan fringing towards the corners if you disable in-camera compensation, or develop raw files without applying corrections. Again, though, it’s easy to correct without detriment to the image.There’s also visible colour fringing in out-of-focus regions when shooting at large apertures, but no more than expected of a fast prime.

Wideangle lenses can often give somewhat fussy, unattractive blurred backgrounds, but not the 28mm. Shot wide open with close subjects, it gives quite attractive bokeh that doesn’t distract the eye from the main subject.

Resolution

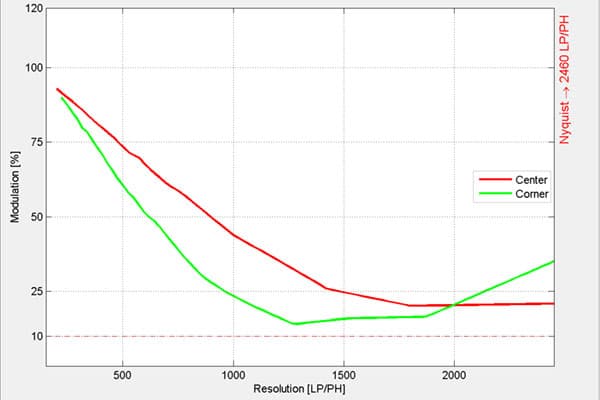

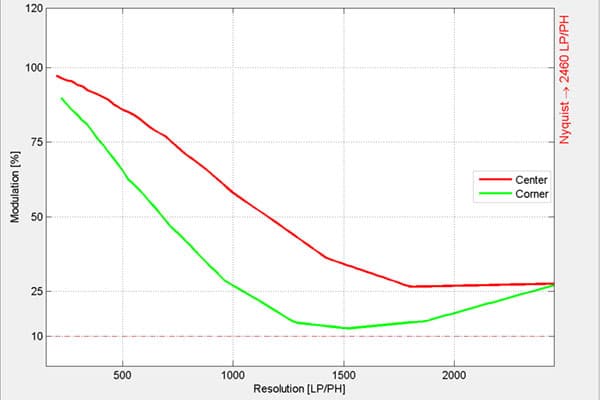

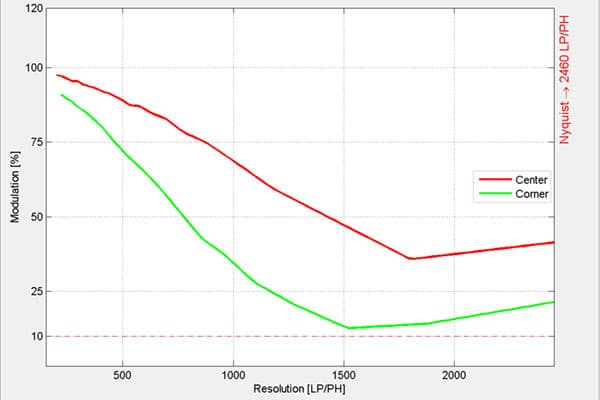

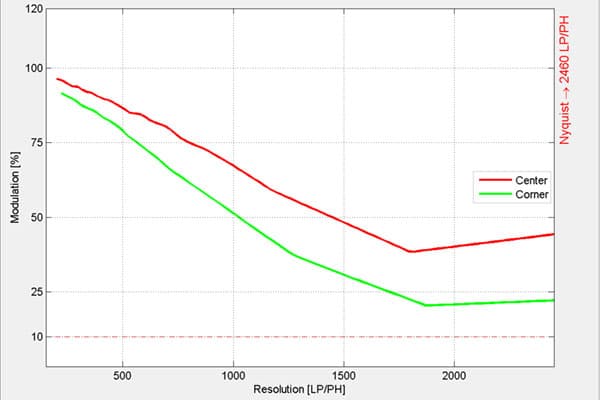

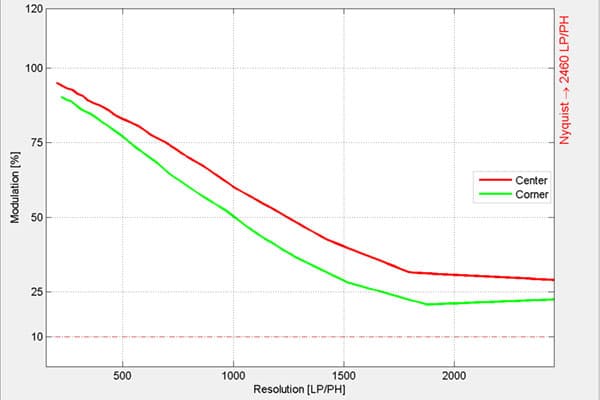

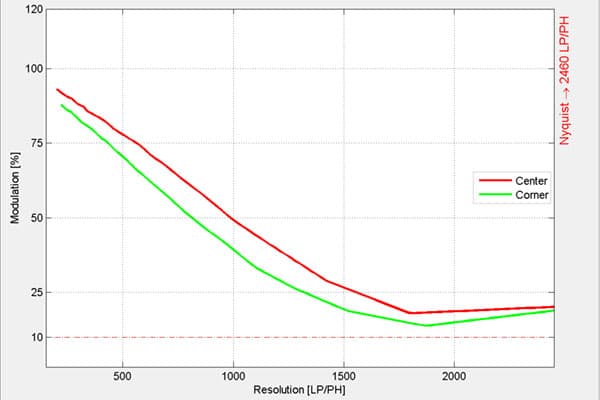

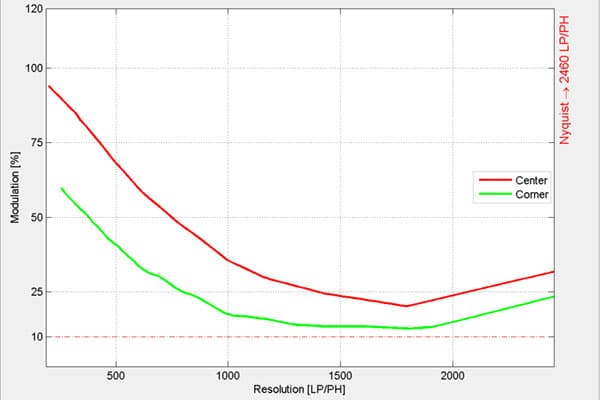

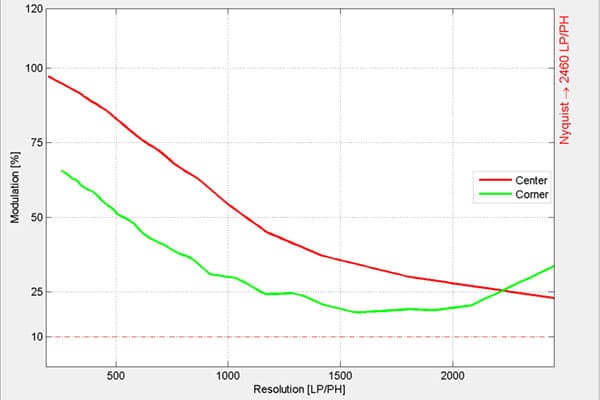

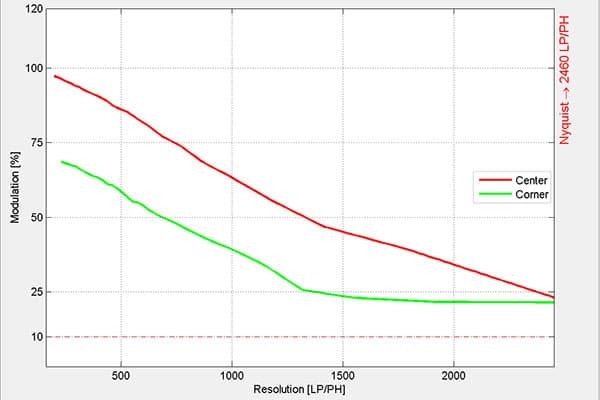

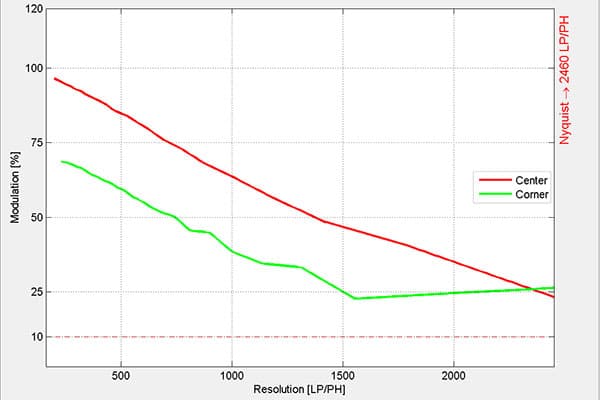

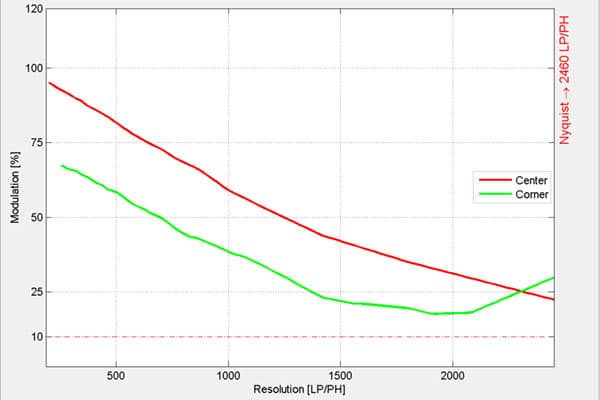

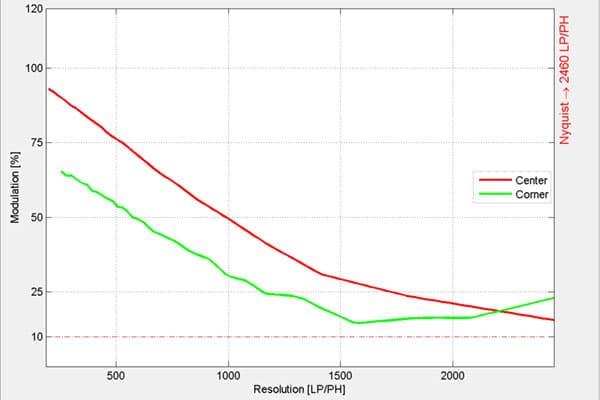

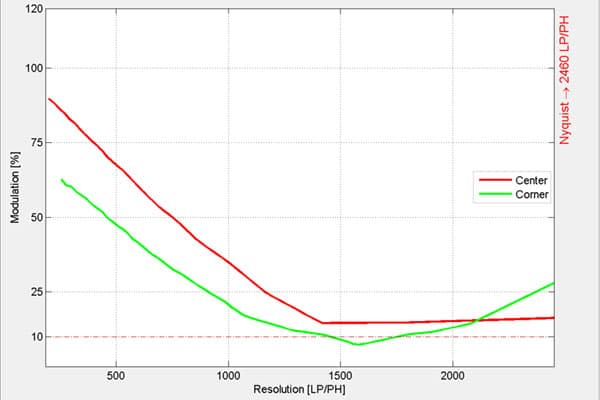

Our Applied Imaging tests reveal the 28mm to behave much as we’d expect for a fast prime. It’s pretty sharp in the centre of the frame wide open, but the edges lag behind. Peak central sharpness is achieved at f/4, with best overall sharpness around f/8-f/11. At smaller apertures the image softens due to diffraction.

Sony FE 28mm f/2, MTF at f/2

Sony FE 28mm f/2, MTF at f/2.8

Sony FE 28mm f/2, MTF at f/4

Sony FE 28mm f/2, MTF at f/5.6

Sony FE 28mm f/2, MTF at f/8

Sony FE 28mm f/2, MTF at f/11

Sony FE 28mm f/2, MTF at f/16

Sony FE 28mm f/2, MTF at f/22

Test Results: Shading and Distortion

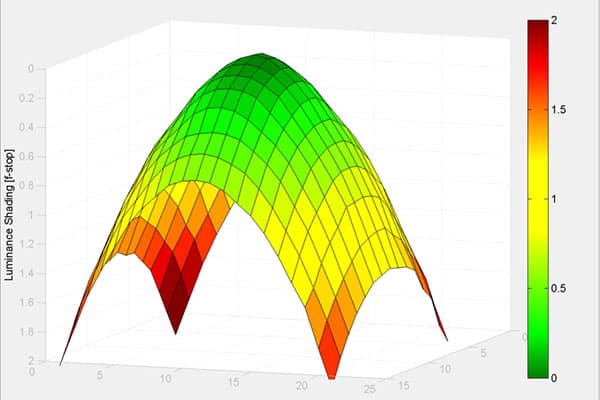

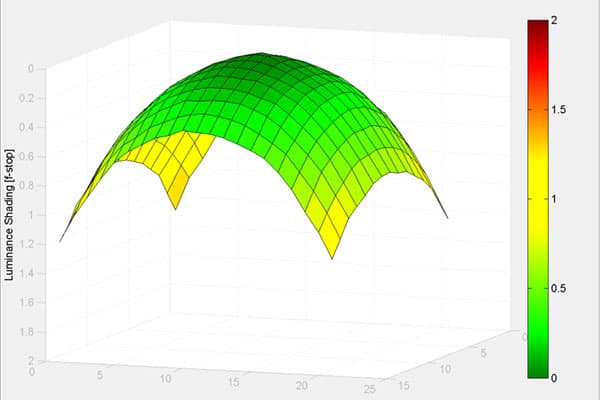

Shading

With shading compensation turned off, the 28mm gives extremely marked vignetting, at more than 2 stops in the corners at f/2 on full frame. Stopping down to f/4 reduces this to about 0.8 stops, beyond which there’s no further improvement. Turning on vignetting compensation essentially eliminates any visible shading effect.

Sony FE 28mm f/2 shading at f/2

Sony FE 28mm f/2 shading at f/2.8

Sony FE 28mm f/2 shading at f/4

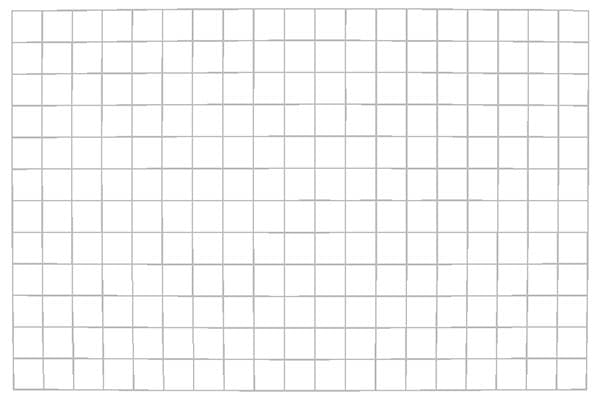

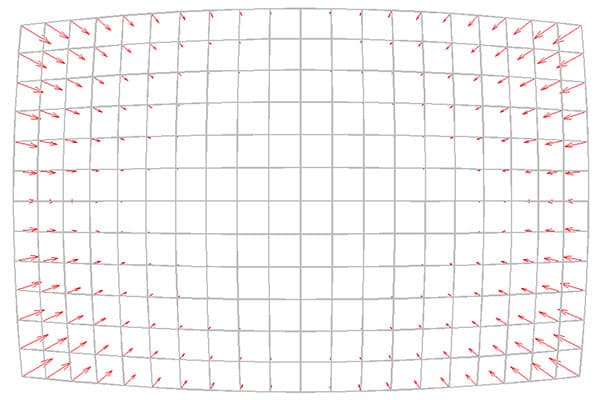

Distortion

Like other CSC lenses the 28mm uses software distortion correction as an integral component of its optical design. This means that JPEG images exhibit essentially no distortion, but uncorrected raw files will show strong barrel distortion. However this is easily corrected during raw conversion, preferably using a specific profile for the lens.

Sony FE 28mm f/2 distortion, JPEG (corrected)

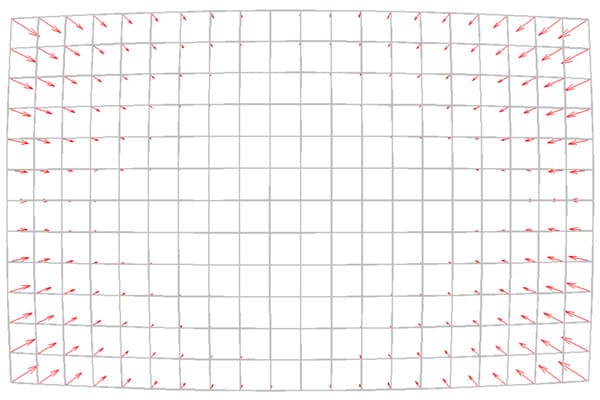

Sony FE 28mm f/2 distortion, raw (uncorrected)

Ultra Wide and Fisheye Converters

What makes the Sony FE 28mm f/2.8 lens really stand out is its compatibility with two purpose-designed add-on lenses, the 0.75x Ultra Wide Converter and the 0.57x Fisheye Converter. These fit onto the bayonet-type hood mount, clicking firmly into place, and are released via sprung, sliding switches on their barrels.

Both adapters have the same standard of construction as the lens, with aluminium-alloy barrels and splash resistance. When attached, they give the impression of being almost an integral part of the lens, although the Fisheye Converter in particular feels quite front-heavy.

Also, both adapters have built-in petal hoods, and cleverly designed caps to fit over them. There’s no way of using filters with them, but this is only really a problem with the Ultra Wide Converter, as fisheye lenses never accept filters. The converters also come with rear caps, which fall off far too easily.

The ultra-wide converter is well-matched to the lens, and released by this sliding switch on the barrel

A sensor in the 28mm lens detects when a converter has been attached, and passes this information on to the camera. This allows it apply the requisite lens corrections, and identify use of the adapters in the image files’ Exif data, which are recorded as FE 21mm f/2.8 and FE 16mm f/3.5 fisheye. From this you can see that the maximum available aperture is limited with each, and Sony says that this is to maintain image quality.

The focal length information is also used by the Alpha 7 II’s in-body image stabilisation system to work correctly.

Ultra Wide and Fisheye Converters: Image Quality

Front-of-lens adapters tend to get a bad press for image quality, mainly because most are budget add-ons that are often used on already-inexpensive lenses. But with this pair, Sony has been able to match the optics specifically to the prime lens, giving combinations that work very well.

Looking first at the Ultra Wide Converter, this is noticeably a bit soft at f/2.8, but improves quickly on stopping down. At f/5.6, only the extreme corners of the frame are soft, and I’d be happy using it for highly detailed landscapes at apertures of f/8 through to f/16. The Zeiss FE 16-35mm f/4 would surely do better, but I doubt that you’d see much difference in an A3 print.

The story is broadly similar with the Fisheye Converter, although with its more extreme optics, smaller apertures have to be used to get the best results. Edges and corners are rather soft and blurry wide open, and the lens has to be stopped down to f/8 at least (and preferably f/11 or f/16) for them to really sharpen up. But at this point, images are impressively crisp across the frame.

Sony FE 28mm f/2 with Ultra-Wide adapter: Resolution

Resolution

Our tests show that the Sony Ultra Wide Converter gives distinctly soft results wide open, but is much better at smaller apertures. Peak sharpness is achieved at f/5.6 through to f/11, although the edges of the frame never quite catch up with the centre. Stopping down further induces diffraction softening, especially at f/22.

Sony 21mm f/2.8 MTF resolution at f/2.8

Sony 21mm f/2.8 MTF resolution at f/4

Sony 21mm f/2.8 MTF resolution at f/5.6

Sony 21mm f/2.8 MTF resolution at f/8

Sony 21mm f/2.8 MTF resolution at f/11

Sony 21mm f/2.8 MTF resolution at f/16

Sony 21mm f/2.8 MTF resolution at f/22

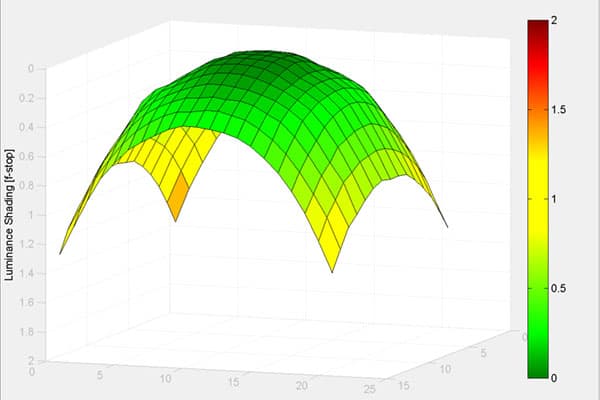

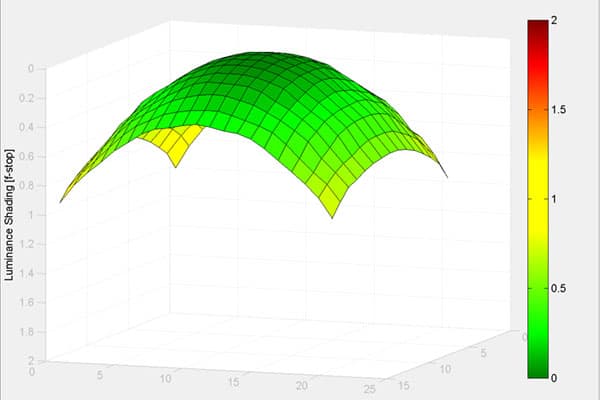

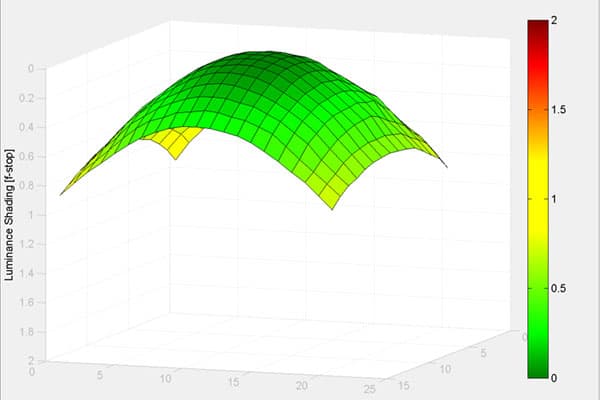

Sony FE 28mm f/2 with Ultra-Wide adapter: Shading

With the Ultra Wide Converter in place, we see moderately strong shading wide open at f/2.8, with around 1.2 stops fall-off in the corners. This drops to around 0.9 stops at smaller apertures. With shading compensation turned on, the camera will correct for it automatically.

It may look surprising that the ultra-wide adapter gives less vignetting wide open than the 28mm f/2 lens alone, but this is simply because the maximum aperture is restricted to f/2.8. If you compare the graph below to that for the lens at f/2.8, you’ll see they’re near identical. This means that the adapter itself introduces no extra vignetting – an advantage of its large domed front element.

Sony 21mm f/2.8 shading at f/2.8

Sony 21mm f/2.8 shading at f/4

Sony FE 28mm f/2 with Ultra-Wide adapter: Distortion

Here we see the benefit of software-aided lens corrections. The Ultra Wide Converter brings distinctly strong barrel distortion when we examine uncorrected images, but because the camera knows all about it, it is able to correct the JPEG output such that only a little residual distortion is left.

Sony 21mm f/2.8 distortion, JPEG (corrected)

Sony 21mm f/2.8 Distortion, raw

Sony FE 28mm f/2 review – verdict

I wasn’t expecting all that much from the little 28mm – with no Zeiss or G badge, it doesn’t overtly boast of its credentials. Yet the more I used it, the more I thought that it’s precisely the kind of FE lens Sony needs to be making for the Alpha 7 system. It offers a combination of decent image quality, relatively large maximum aperture, compact size and reasonably affordable price that hitherto has been lacking from the company’s full-frame E-mount range.

This 28mm lens may not be quite as optically stunning as the Zeiss-branded 55mm f/1.8 or 35mm f/2.8, but it’s still pretty sharp wide open, and once it’s stopped down to normal working apertures of, say, f/5.6 to f/11, it’s very good indeed. It’s also small and light enough to slip into your bag and carry around, where larger lenses may be left behind.

Sony’s matched adapters also work rather well with the 28mm f/2 lens, and when used with care they can give very good image quality. In terms of operation, there’s little compromise, either. For example, autofocus and metering are completely unaffected. Indeed, my main gripe is that you can’t use filters with the Ultra Wide Converter.

Despite this, though, if I were buying the 28mm lens, I’d probably get it in a kit with the Ultra Wide Converter, simply because it gives another useful focal length for not a lot extra money. I’m more ambivalent about the Fisheye Converter, because it’s distinctly bulky and I don’t have much use for fisheyes in general. Then again, it does give an inexpensive option for occasional use.