Sigma sd Quattro review: Introduction

At a glance:

Foveon X3 Quattro APS-C sensor

ISO 100-6,400

2.36-million-dot EVF

£799 body only

£999 with 30mm f/1.4 lens

Sigma is best known as a leading third-party lens producer, but it also has a long history of selling cameras. Having made a couple of 35mm SLRs with its proprietary all-electronic SA lens mount, its first DSLR appeared in 2002, based around the unique triple-layer Foveon X3 sensor.

While it has understandably not been very prolific with new models, Sigma has maintained a constant, if low-key presence in the camera market. Its current dp Quattro fixed-lens compacts have a clear, if somewhat niche appeal, with exceptional lenses and superb image quality at low ISOs. The camera we’re considering here, the sd Quattro, uses the same sensor, but with interchangeable lenses. It’s one of a pair of externally identical cameras, with the sd Quattro-H differing in having a larger, higher resolution 25.5-million-pixel sensor with a 1.3x crop.

With the new model, it appears that Sigma has learned some difficult lessons from its experience with the ill-fated SD1 DSLR of 2010, which was underpowered and overpriced. First, with a body-only price of £799, the new sd Quattro is much more reasonably priced. Second, while it’s based around the same SA mount, the model is not an SLR at all, but a mirrorless camera with an electronic viewfinder.

So what does this mean? When you remove the lens and look inside the mount, there’s no mirror, just a deep empty tube back to the camera’s sensor. This is normally exposed with the shutter open, so it can provide a full-time, live-view feed to either the rear screen or the eye-level viewfinder. The advantage is that the camera’s mechanical complexity is greatly reduced (and therefore its cost); yet it retains the ability to use all the SA-mount lenses Sigma has made over the years. The disadvantage is that you get little of the size and weight saving typical of CSCs.

Sigma isn’t the first company to try building a mirrorless camera around an SLR mount; the self-consciously quirky Pentax K-01 used the same concept. However the sd Quattro has altogether higher aspirations to be a serious photographic tool. While it’s much more affordable than its predecessor, it’s still in the same price bracket as hugely capable enthusiast-level DSLRs and CSCs such as the Nikon D7200 or Olympus OM-D E-M5 Mark II. So, has Sigma done enough to make it a competitive alternative?

Sigma sd Quattro review: Features

The sd Quattro’s most important feature is its Foveon X3 Quattro image sensor. Unlike conventional sensors, which use a pattern of red, green and blue-coloured filters over their light-sensitive photodiodes to determine colour, it’s based around the fact that the different colours of light can penetrate silicon to different depths. It has a top layer with 19.6 million pixels that’s most sensitive to blue light, with two layers beneath that each use 4.9 million pixels four times in area, and that are sensitive to green and red light. Because of this arrangement, Sigma calls it a 29.5-million-pixel sensor.

This unique approach means that its X3F raw files can only be processed using Sigma Photo Pro (SPP). Unfortunately, this is one of the slowest and least intuitive pieces of software I’ve ever used, and it’s a serious weakness of the entire system. It’s capable of delivering good results, but you’ll need a fast, up-to-date computer and the patience of a saint.

On paper, the sd Quattro looks like a reasonably well-equipped camera. Its output resolution is 19.6 million pixels, although the unusual design of the Foveon sensor promises to capture finer detail and colour gradation compared to a conventional Bayer sensor with a similar pixel count. The sensitivity range covers a decidedly modest ISO 100-6,400, and files can be captured in the 14-bit losslessly compressed X3F raw format. These can now be converted to JPEGs in-camera after shooting, with plenty of control over processing parameters such as brightness and white balance.

Shutter speeds range from 1/4000sec to 30secs, with a bulb option and 1/180sec flash sync speed. Continuous shooting is available at 3.6fps with a 12-frame raw buffer, and files are recorded to a single SD card. In keeping with the camera’s market positioning, only the four key exposure modes – program, aperture priority, shutter priority and manual – are on offer.

As is usual for mirrorless cameras, both autofocus and metering employ the main imaging sensor. According to Sigma, AF uses a hybrid system with both phase detection and contrast detection on board; users can either select from a nine-point mode, or move the focus area freely across a space roughly 75% of the height and width of the frame. The focus area can also be changed in size in three steps, including a fine point for focusing on a precise part of the scene. Face detection is also available.

One unusual addition is Sigma’s new SFD mode, standing for ‘super fine detail’. While this superficially resembles the high-resolution modes found in recent Pentax and Olympus models by shooting a series of exposures and combining them into a single raw file, here it brackets seven shots at 1-stop increments. In essence, this makes it a high dynamic range mode, designed to record extra detail in the shadows and highlights for post-processing. I’ll look into how well it works later.

Other features are notable by their absence. There’s no built-in flash: you can use either a hotshoe-mounted unit or employ the PC sync port on the front plate. Unusually for a modern camera, the sd Quattro has no video mode, and Wi-Fi connectivity is missing too, although support for Eye-Fi cards is included.

Sigma sd Quattro review: Build and handling

When you first pick up the sd Quattro, it’s clear that this is the least conventionally designed interchangeable-lens camera around. It’s as large as an enthusiast DSLR, such as the Nikon D7200, but rather oddly shaped, with a flat top-plate but scalloped base and a viewfinder that’s unusually offset towards the right-hand side.

There’s little to complain about in terms of build quality, with the dust and splash-proofed magnesium-alloy body feeling solid in your hands, helped by the chunky grip. The twin electronic control dials rotate with satisfying detents, with sufficient resistance that they won’t get accidentally knocked, but without being too stiff. All the switches click positively into place, and the buttons that festoon the body have a deep travel with positive end points.

Sigma’s interface is very clear and logical, with sensibly laid-out menus and attractive viewfinder displays that are informative without being overwhelming. There’s a decent amount of customisation on offer too: you can define exactly how the control dials work in each exposure mode, and configure the on-screen QS menu to give speedy access to your most-changed functions.

However it’s the positioning of the buttons and switches that’s often perplexing. The power switch is placed awkwardly on top of the protruding lens mount, and there’s a second sliding lock switch behind the shutter button that, by default, disables almost all the control buttons but not the shutter button or dials. I set it to send the camera to sleep mode and conserve battery, which makes more sense to me, but I’d rather see a single easily accessible power switch.

The D-pad on the back of the body is large and positive, and perfectly placed for moving the focus point around the frame while you’re shooting. But unlike most cameras you can’t do this directly; instead, you first have to press a small button towards the bottom of the camera body that requires considerable movement of your thumb to locate. As the D-pad buttons have no other direct function, this seems like an unnecessarily awkward extra step.

The ISO button is also poorly placed in the middle of a column of five identical tiny buttons beside the screen, so is difficult to identify by touch alone. On other cameras this would be a serious criticism, but less so on the sd Quattro, as its poor high ISO performance means you probably want to keep the camera set to ISO 100 as much as possible, anyway.

After spending a bit of time using the sd Quattro and tweaking its set-up, I found it to be a perfectly usable camera. But I can’t help think that Sigma’s unconventional design pays few real dividends. The reality is that DSLRs and DSLR-shaped mirrorless models are popular for a reason – their shape and layout help make them very quick to use.

Sigma sd Quattro review: Viewfinder and screen

On paper, the sd Quattro has a bang up-to-date viewfinder and screen. Its EVF uses a 2.36-million-dot panel and offers a magnification equivalent to 0.73x. The 3in rear screen has a 1.62-million-dot resolution, although it’s fixed rather than articulated and not touch-sensitive. One nice feature is the addition of a small OLED sub-monitor alongside the LCD that displays key settings such as shutter speed, aperture, metering mode, ISO and exposure mode.

In practice, both the viewfinder and screen are bright, clear and sharp. But they’re badly let down by a low-resolution live-view feed, which appears pixelated and over-sharpened. This is particularly obvious when using the EVF, and is a shame because the rest of the on-screen interface is so good.

One nice touch is a large switch beside the eyepiece that allows you to select between viewing with the EVF or LCD or changing between the two automatically using an eye sensor. It’s much more intuitive and satisfactory than having to cycle between modes by pressing a button, and I wish more camera makers would follow suit. When using the EVF, the rear screen can be set to display the camera’s detailed status, or turned off completely to conserve power.

I mostly preferred to use the electronic viewfinder, reverting to the rear screen for tripod work. The EVF’s position to the right of the camera does feel odd, but it works OK when you get used to it. The large eyecup does a great job of blocking glare, and because it protrudes so far from the back of the camera, there’s no problem accessing any of the buttons with the camera to your eye.

The sd Quattro will preview your exposure, white balance and colour mode, giving a good idea of how the image should turn out before you press the shutter button. Lots of useful extras can be overlaid on the live-view display, including gridlines, a dual-axis electronic level display and a live histogram. Indeed, users can configure up to four custom views each for the EVF and LCD, and cycle through them using the display button.

Mystifyingly, I could find no way of engaging depth of field preview; instead, the camera always views with the lens set wide open. This is one area where mirrorless cameras should have significant advantages over DSLRs, as their electronic viewfinders can show accurate depth of field at large apertures and don’t necessarily go dark at small apertures.

Sigma sd Quattro review: Autofocus

One disadvantage of using DSLR lenses on a mirrorless camera is that they’re often slow to focus, as their autofocus motors and optical designs are optimised for phase- detection autofocus. Sadly, Sigma hasn’t found any magic solution to this, and with the 30mm f/1.4 DC HSM | Art lens I used for testing, the AF speed could best be described as ‘leisurely’. I found it adequate for static subjects, but wouldn’t even think of trying it with anything that moves. Of course, it’s possible that the camera might function better with other lenses.

Many users, however, will be tempted to focus manually, and here the sd Quattro offers some useful aids. A peaking display can be turned on in the menus with a choice of four colours, although it can’t be set up as a custom viewfinder display. When the lens is switched to manual focus, pressing the button in the centre of the D-pad engages magnified live view for the most accurate focusing, and the area of interest can be moved around the frame as in AF mode.

The sd Quattro isn’t the best choice for anything that requires quick focusing, such as street photography. But its limitations will be of less concern with the subjects that the Foveon sensor best lends itself to, such as macro, still life or landscapes.

Sigma sd Quattro review: Performance

In use, the sd Quattro is a reasonably responsive camera, and the slow processing and write times that plagued the SD1 Merrill are gone. It’s not going to challenge similarly priced enthusiast DSLRs for speed, especially when used in its resource-hungry SFD mode, but it won’t leave you waiting much, either.

Its main flaw is an unusually long viewfinder blackout time, particularly if you have quick preview enabled for checking each image after shooting. However, this is handy to keep turned on, as it helps you to spot when the sd Quattro’s white balance or metering have been errant.

This isn’t to suggest that either is wildly unreliable – indeed, most times the sd Quattro gives nicely judged, attractive images. But it’s less consistent than some if its peers and can be prone to over-neutralising atmospheric lighting such as warm evening sunlight.

It will occasionally overexpose too, clipping highlights in an unusually inelegant fashion. Attempting to recover any lost highlight detail in SPP reveals that there’s very little room to manoeuvre, as ugly hue shifts appear. But you can’t underexpose too much, as then you’ll see noise when pulling up shadow detail.

When you do get things spot on, then at ISO 100 the Foveon sensor delivers remarkable results, with stunning detail and subtle colour gradation. Unfortunately, you don’t have to raise the sensitivity very much for all this to go wrong, and by ISO 800 blotchy green and purple shadow noise becomes a real problem. Above this the JPEG resolution takes a nosedive, with the camera apparently processing at the 4.9MP resolution of the two lower sensor layers, then upscaling to 19.6MP. There’s little in the way of shadow detail, too.

Sigma sd Quattro review: Dynamic range, noise and resolution

Like the dp Quattro compacts we’ve already tested, the sd Quattro’s Foveon X3 sensor offers a decidedly Jekyll and Hyde approach to image quality. At low-sensitivity settings of ISO 100-400 it’s excellent, with astonishing pixel-level detail. But at high ISOs it’s awful, lagging far behind conventional Bayer sensors. In what appears to be a tacit admission of this, Sigma Photo Pro 6.4, by default, now drops the output resolution to 4.9MP at ISO 800 (2,712×1,808 pixels), 2.2MP at ISOs 1,600 and 3,200 (1,808×1,205 pixels), and just 1.2MP at ISO 6,400 (1,356×904 pixels). It’s still possible to extract full-size images if you prefer, but they’re not great.

Dynamic range

As we’ve seen previously, our Applied Imaging dynamic range analysis software won’t sensibly handle the Foveon sensor’s X3F raw files, so we can’t reproduce our usual graph here. Empirically, though, the camera delivers reasonably decent dynamic range at ISO 100, although it can’t match the latest conventional APS-C sensors in terms of shadow detail recovery. When shooting JPEGs, the in-camera tone control helps with getting the maximum amount of shadow and highlight detail into the files, and when shooting in raw, Sigma Photo Pro’s X3F Fill Light tool does a particularly effective job, although it can easily be overdone. Above ISO 800, dynamic range is very limited with considerable levels of noise in shadow regions.

Noise

Characteristic of the Foveon sensor, at low sensitivities the sd Quattro gives excellent image quality, with attractive colours and remarkable amounts of ultra-fine detail. But even at ISO 100 some gritty luminance noise is visible when viewing images at the pixel level, along with hints of green-and-purple chroma noise, although you won’t see this in print. At just ISO 400 both are more visible in neutral midtones and colour saturation is deteriorating. At ISO 800 colour is further subdued and detail starts to smudge away.

Noise is better suppressed when using raw: above we’re showing SPP’s default pixel-binned output at higher ISOs. This has the effect of reducing the visibility of pixel-level noise, but even so I wouldn’t venture beyond ISO 1,600. This is poor for an APS-C camera, and severely limits the camera’s versatility.

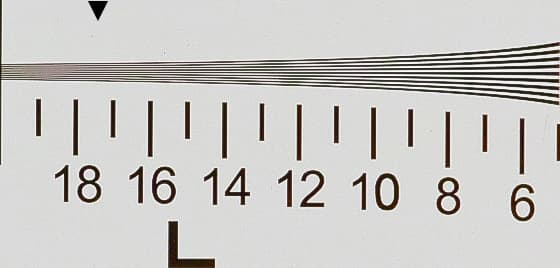

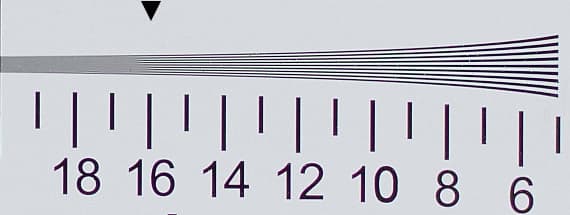

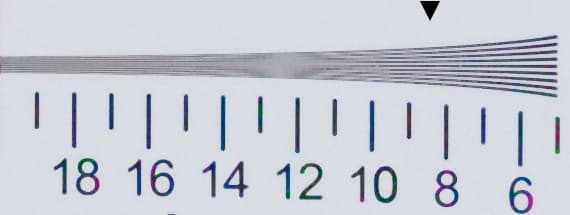

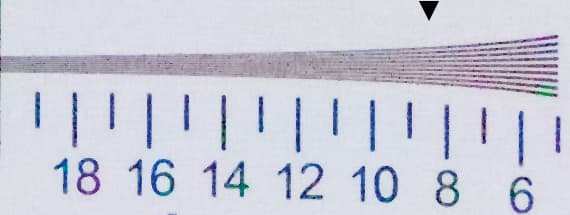

Resolution

In raw mode the sd Quattro resolves an impressive 3,500l/ph, which is about as high as its sensor could theoretically deliver, and with none of the false colour artefacts that Bayer sensors can display. However, Sigma’s JPEG processing reduces this to around 3,200l/ph at ISO 100. This is maintained reasonably well to ISO 800, but at ISO 1,600 JPEG resolution plummets to around 1,800l/ph owing to a change in processing mode. At higher settings noise increases markedly, but has little effect on measured resolution.

Sigma sd Quattro review: Super Fine Detail Mode

One potentially useful new feature on the sd Quattro is its SFD mode. This takes seven bracketed exposures in 1-stop steps from a single press of the shutter, covering an overall range of ±3EV. These are then combined into a single X3I raw file – essentially seven concatenated X3Fs – and saved together. The idea is that by bracketing so widely, the camera should record a full range of detail from bright highlights to deep shadows, which can then be brought out in post-processing without excessive noise appearing. In essence, this makes up for the sensor’s relatively limited dynamic range.

Here SFD mode (bottom) has recorded a much greater range of tones than the JPEG (top) in both the highlights and shadows

As with other multi-shot modes, you have to lock the camera down on a tripod to ensure it doesn’t move between exposures – anything moving in the scene could cause problems. Sigma automatically sets the ISO to 100, and it makes sense to use the 2sec self-timer to avoid vibrations. The resultant X3I files are vast – almost 370MB – and can’t be processed in-camera, only using Sigma Photo Pro. This turns out to be the biggest problem, as developing them takes forever. By default, files are output in a minimally processed state with low contrast, saturation and sharpening, presumably on the basis you’ll work them up further.

However, in favourable situations SFD mode can bring clear benefits; in the example above I used it to record detail in a bright sky and dark foreground that the sensor simply couldn’t capture in a single exposure. But like other multi-shot modes, it’s not very convenient to shoot or process.

Sigma sd Quattro review: Verdict

There are two ways of looking at the sd Quattro. First, is it a realistic competitor for a similarly priced enthusiast DSLR or CSC? Sadly, the answer is probably not, at least for the majority of photographers; it’s difficult to recommend building up an SA-mount lens set to use with such a specialised camera. Landscape shooters happy to bolt it to a tripod and always work at ISO 100 might appreciate the unique qualities of the Foveon sensor, but it’s difficult not to conclude that the majority of photographers would be better served by an up-to-date APS-C DSLR or CSC instead. Almost any other interchangeable-lens camera will give faster autofocus and much better high ISO performance, and therefore increased shooting flexibility. The fact that its raw files can only be processed using Sigma Photo Pro is also a serious liability; this software is simply too slow and clunky to offer any kind of sensible workflow unless you only plan on processing a very limited number of shots at any given time.

However, for existing Sigma system users who already own SA-mount lenses, the Quattro is a clear step forward from previous sd cameras in almost every meaningful way, and easy to recommend as an update. It’s faster and more responsive in most aspects of operation, let down mainly by its hesitant autofocus and relatively long viewfinder blackout time. It doesn’t offer huge image-quality benefits over the SD1 Merrill (indeed, some users may well prefer the results from the previous generation sensor), but it certainly improves markedly on older models such as the SD15.

Ultimately, the sd Quattro was always going to stand or fall on the properties of its Foveon sensor. Unfortunately, it mostly falls; it’s all very well having lots of detail at low ISO, but this is outweighed by the poor high ISO capability and clunky raw software, especially as conventional 16MP or 24MP Bayer sensors are easily up to the challenge of producing high-quality A3 prints anyway. With neither the portability of a mirrorless CSC nor the speed of a DSLR, it’s one for Sigma aficionados only.