Full-frame mirrorless cameras have been grabbing all the headlines over the past 18 months, as they provide excellent image quality in relatively small bodies. But their lens systems have, if anything, grown larger and more expensive than their DSLR counterparts, due to the current fashion for prioritising corner-to-corner sharpness. Usually photographers have relied on third-party lens makers to produce more affordable alternatives, but the relative newness of Canon and Nikon’s mirrorless systems means that few are yet available for them.

The Meike MK 50mm F1.7 is designed for use on full-frame mirrorless cameras

However some manual focus optics are starting to appear, aided by the fact that they just need to copy the mount’s physical specifications, and the electronics. One interesting option is the Meike MK 50mm F1.7. It’s a fairly compact standard prime that can be bought from online marketplaces such as Amazon and eBay for well under £150. Unlike many other inexpensive manual lenses, it’s both designed for mirrorless, and covers full frame. It’s made in Canon RF, Nikon Z, Sony E, Fujifilm X and Micro Four Thirds mounts: I’ll look at how well it works on full frame, using Sony’s Alpha 7-series bodies.

Meike MK 50mm F1.7: Features

In terms of optical construction, the lens employs six elements in five groups, implying a classic double-Gauss design of the type that’s been used by 50mm primes for decades. The rear element is quite deeply recessed into the barrel, so it’s tempting to assume that Meike has simply copied an old SLR lens, and added a spacing tube onto the back to account for the shorter flange distance of mirrorless mounts.

However, a more detailed comparison shows that this isn’t true, and the design has genuinely been modified for mirrorless. The entire optical system sits closer to the sensor than would be possible with an SLR design, and the rear element has been considerably enlarged, which potentially allows better illumination of the corners of the sensor.

As a result, the Meike 50mm f/1.7 is considerably more compact than Sony’s inexpensive FE 50mm F1.8, and almost exactly the same size as the Samyang AF 45mm F1.8 FE, which employs a completely different, designed-for-mirrorless optical formula. It also ends up shorter than any SLR-mount fast 50mm used on a mount converter, being closer in length to an adapted rangefinder lens.

One area where Meike has catered to modern sensibilities regards the diaphragm, which employs 12 curved blades to give a circular aperture. This promises more attractive bokeh at intermediate apertures than SLR equivalents, which typically use seven blades, or sometimes even fewer.

The diaphragm is mechanically coupled to the aperture ring, meaning that it stops down directly to the indicated setting. This in effect gives a full-time preview of depth of field, with the camera’s viewfinder automatically gaining up to compensate for the reduced light reaching the sensor at smaller settings.

Like most conventional 50mm primes, the minimum focus distance is limited to 50cm. You can get closer using extension tubes, of course, but will need to stop down considerably to get sharp results. The filter thread is 52mm, and doesn’t rotate on focusing, which facilitates using filters such as polarisers. A deep petal-style plastic lens hood is supplied and bayonets firmly into place, while reversing neatly for storage.

It’s worth repeating that this lens has no electronic connection with the camera. As a result, the selected aperture isn’t displayed in the viewfinder while you’re shooting, and neither the focal length nor the aperture will be recorded in your images’ EXIF data. On cameras with in-body image stabilisation, you’ll also need to set the focal length manually for the system to work correctly. This is one area where more sophisticated manual-focus lenses from the likes of Voigtländer and Zeiss offer a clear advantage, but naturally, they’re far more expensive.

Meike MK 50mm F1.7: Build and Handling

Pick up the Meike and you’ll immediately appreciate that it’s a substantial piece of kit, with a solid-feeling metal barrel. Indeed at 310g, it’s almost twice the weight of the Samyang 45mm f/1.8 or the Sony 50mm f/1.8. Even so the lens balances very nicely on Sony’s Alpha 7-series bodies, and both the control rings rotate extremely smoothly, without a hint of backlash.

The focus ring displays a distance scale in feet and metres, but disappointingly there are no depth-of-field markings, meaning that you can’t easily work with zone-focusing techniques. Some photographers will also be dismayed to find that the aperture ring lacks click-stops to help make quick adjustments, suggesting that the lens was designed with video equally in mind. As a result, you’ll need to take the camera down from your eye whenever you want to change the aperture.

The spacing between the whole-stop markings isn’t even, either; instead they start out widely separated at large apertures, but become heavily bunched together beyond f/8. In fact the markers for f/11 and f/16 are just dots, so don’t expect to be able to set them with any great precision.

In practical use, perhaps the biggest irritation lies with the fact that there’s no clear difference in feel between the focus and aperture rings, making it easy to confuse the two with the camera up to your eye. More than once I found myself changing the aperture when I was trying to focus.

Meike MK 50mm F1.7: Focusing

On one level, this lens is about as simple as it gets when it comes to focusing. It’s manual only, so simply turn the focus ring until the picture is sharp. As the camera can’t know when you’re adjusting the focus, it makes sense to assign your favourite aid, such as live view or peaking, to a custom button that’s easy to locate when you’re looking through the viewfinder. The focus ring is easy enough to turn with two fingers, but sufficiently taut that you’re unlikely to displace it by accident.

Accurate focusing is made easier by placing your preferred focus aid on an easy-to-reach button. Sony Alpha 7 II, Meike MK 50mm F1.7, 1/1250sec at f/1.7, ISO 400

As the diaphragm stops down directly, you’ll naturally end up focusing at the taking aperture. For died-in-the-wool SLR users used to focusing with the aperture wide open, this will seem all wrong. But in this case it’s the more accurate approach, because the lens turns out to exhibit significant focus shift on stopping down. This behaviour is due to spherical aberration, where the outer regions of the optical unit that are used at large apertures don’t focus light at exactly the same distance as the central portion. This is an unavoidable flaw on large-aperture primes that don’t use aspherical elements, but the Meike 50mm f/1.7 seems to suffer from it more than most.

Meike MK 50mm F1.7: Performance

I tested the Meike MK 50mm F1.7 on the 24MP Sony Alpha 7 II and III bodies, using magnified view as my preferred focusing aid, activated by the C1 button behind the shutter release. This is slower than using a peaking display, but demonstrably more accurate when you want to achieve precise focus at large apertures. In an unexpected quirk, both cameras consistently underexposed images shot with the Meike lens, generally needing 0.7 to 1 EV exposure compensation.

This image required +1 stop exposure compensation on the Sony Alpha 7 II to match a reference AF lens. Sony Alpha 7 II, Meike 50mm F1.7, 1/320sec at f/8, ISO 100

In terms of image quality, the lens initially appears to behave similarly to other double-Gauss 50mm primes. Wide open, it’s capable of resolving fine detail in the centre of the frame, but at rather low contrast as a result of its spherical aberration. However the edges and corners are notably blurred.

At large apertures, the edges of the image are unusually blurred. Sony Alpha 7 II, Meike 50mm F1.7, 1/1250sec at f/1.4, ISO 100

You’ll also see intense vignetting, but this should be viewed as an aesthetic characteristic rather than a flaw; it’ll actually complement many subjects, and disappears by f/4 anyway. There’s a hint of barrel distortion, but most of the time it’s not worth worrying about.

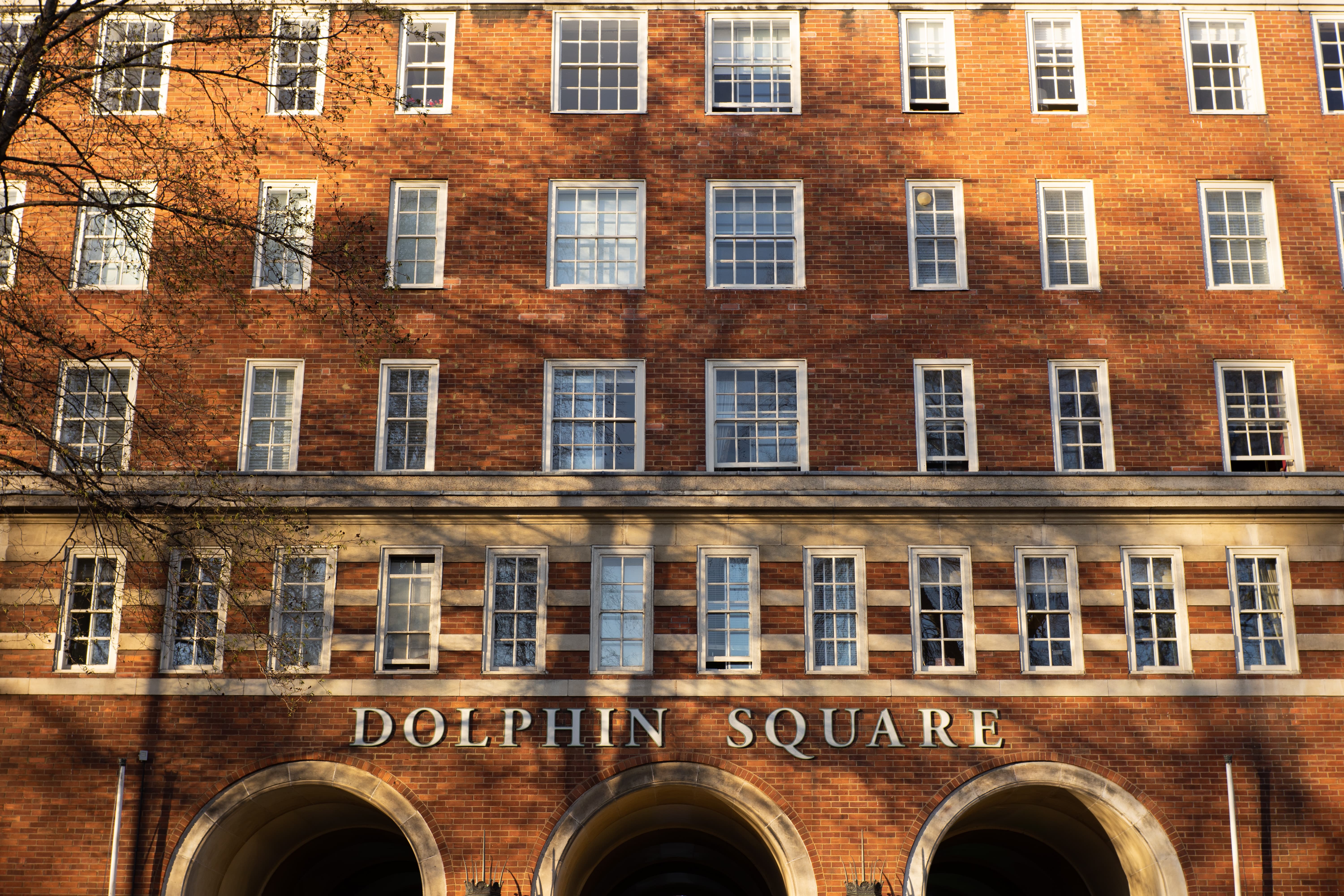

Images show a hint of barrel distortion. Sony Alpha 7 II, Meike MK 50mm F1.7, 1/100sec at f/8, ISO 100

As you stop down the aperture, the sharp central region gets crisper, but strange things happen with the corners, which barely sharpen up at all until about f/5.6. Then they suddenly start to pick up, and by f/11 the lens is capable of resolving fine detail right across the frame. Closer analysis reveals that the optics suffer from marked curvature of field, with the corners of the frame coming into focus at a closer distance than the centre, which accounts for much of their apparent softness.

With a small aperture, and a favourable subject, images are sharp from corner-to-corner. Sony Alpha 7 II, Meike MK 50mm F1.7, 1/60sec at f/8, ISO 250

This also means that you may be able to get better sharpness towards the edge of frame by careful re-focusing, but at the expense of central detail. Throw in its focus shift on stopping down, and the Meike is certainly much less well-behaved optically than the 50mm primes that were traditionally supplied with manual-focus film SLRs.

Out-of-focus backgrounds are attractively blurred. Sony Alpha 7 II, Meike MK 50mm F1.7, 1/60sec at f/1.7, ISO 200

Where the lens does excel, though, is with regards to bokeh. Out-of-focus backgrounds are rendered with a smooth, attractive blur, which is the flip-side of that under-corrected spherical aberration. The circular diaphragm also keeps the bokeh more attractive when the aperture is closed down a stop or two. As a result, the lens is really well-suited to selective-focus work such as portraiture.

Meike MK 50mm F1.7: Resolution

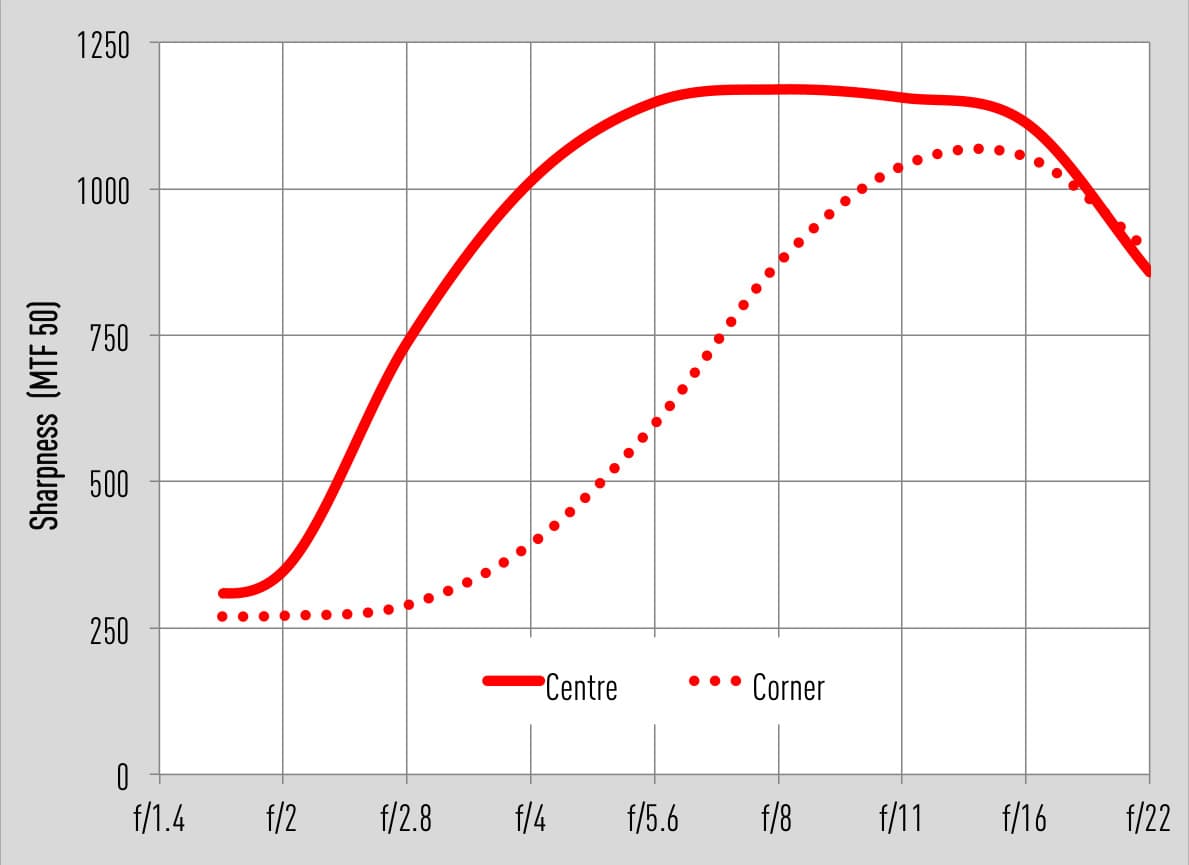

Our Image Engineering MTF50 tests, conducted on the 24MP Alpha 7 III, reveal the lens’s unusual sharpness profile. The very low numbers at large apertures reflect low contrast due to spherical aberration, but central sharpness picks up rapidly at smaller apertures, and is excellent by f/5.6. But you need to stop all the way down to f/11 for the corners to catch right up, at least with a relatively flat subject.

Meike MK 50mm F1.7, MTF50, tested on Sony Alpha 7 III

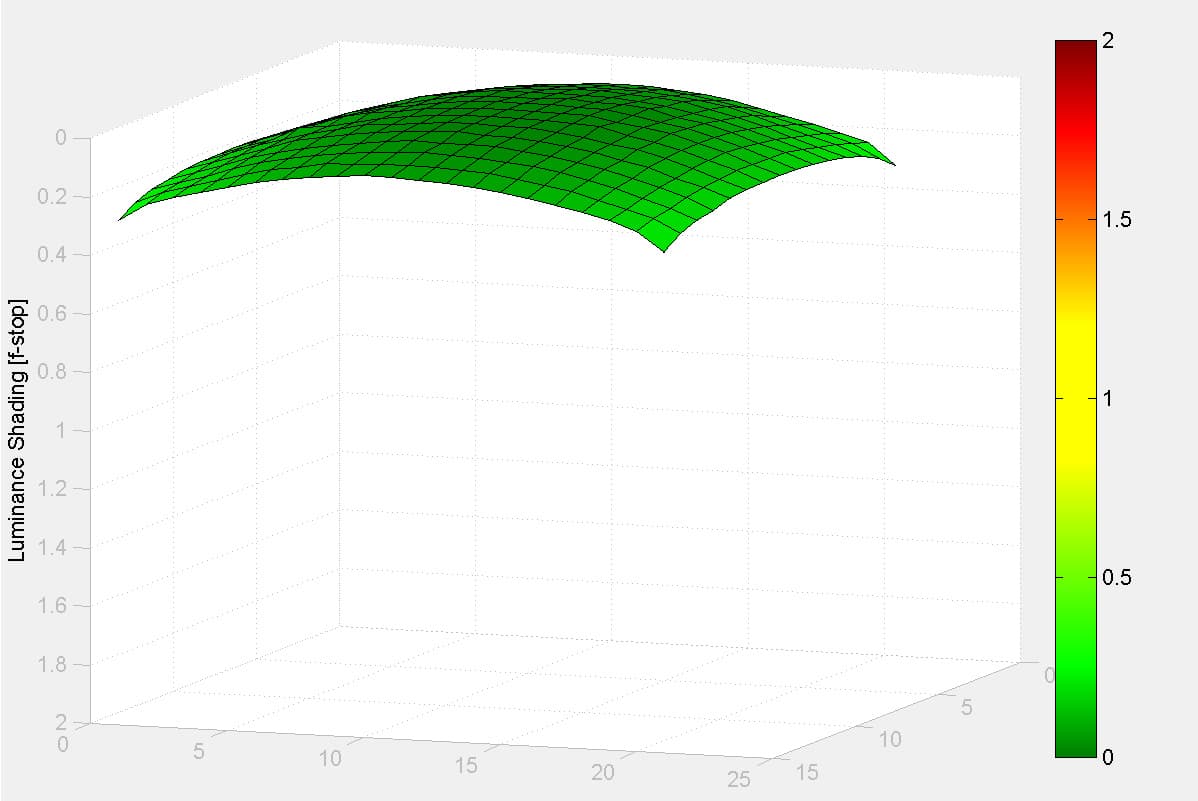

Meike MK 50mm F1.7: Shading

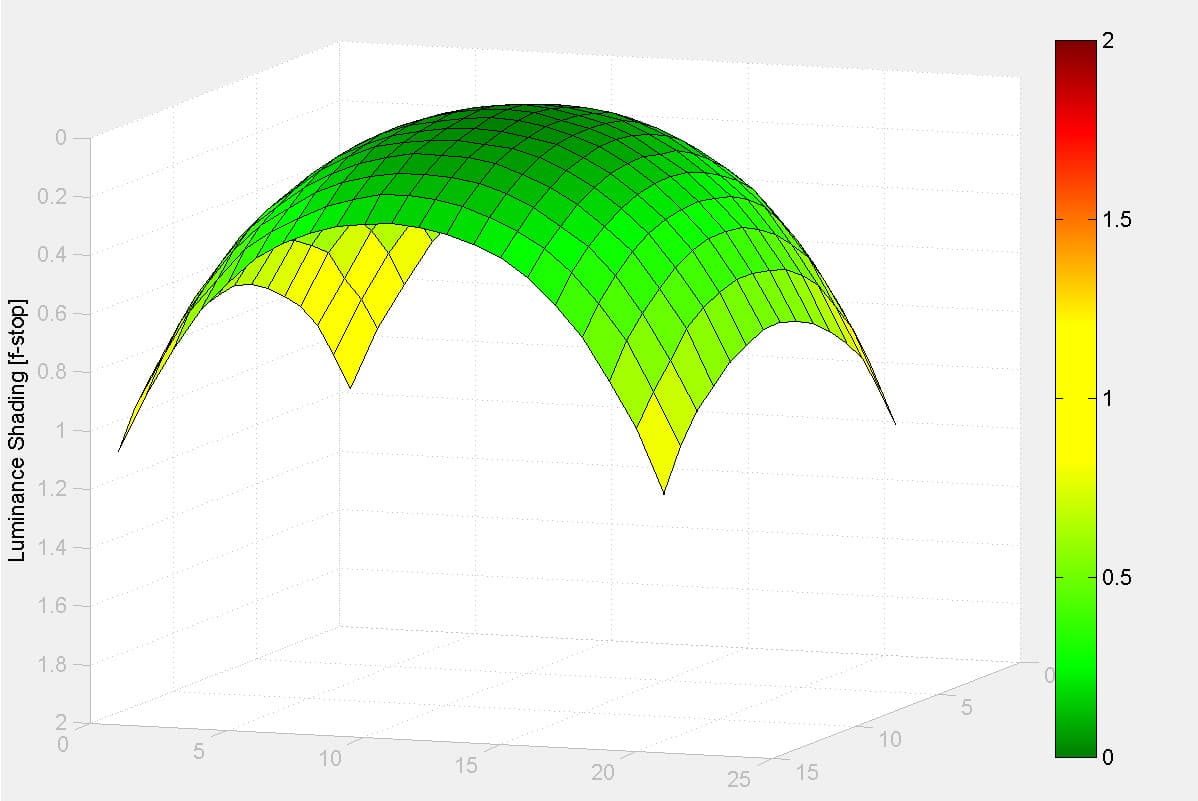

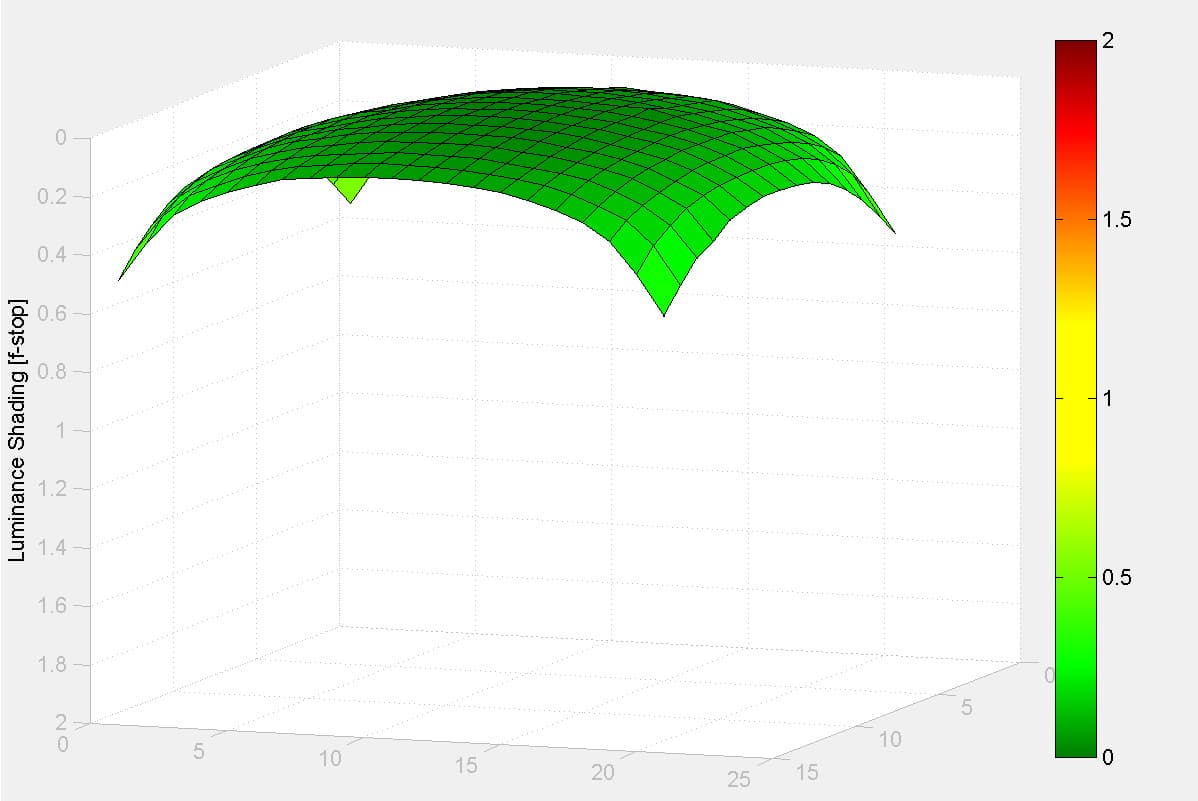

As is typical for fast primes we see fairly strong vignetting wide open, with more than a stop lower illumination in the corners of the frame compared to the centre. But the effect goes away rapidly on stopping down: at f/2.8 we see just a little darkening in the far corners, and by f/4, the effect has gone altogether.

Meike MK 50mm F1.7: Shading at f/1.7

Meike MK 50mm F1.7: Shading at f/2.8

Meike MK 50mm F1.7: Shading at f/4

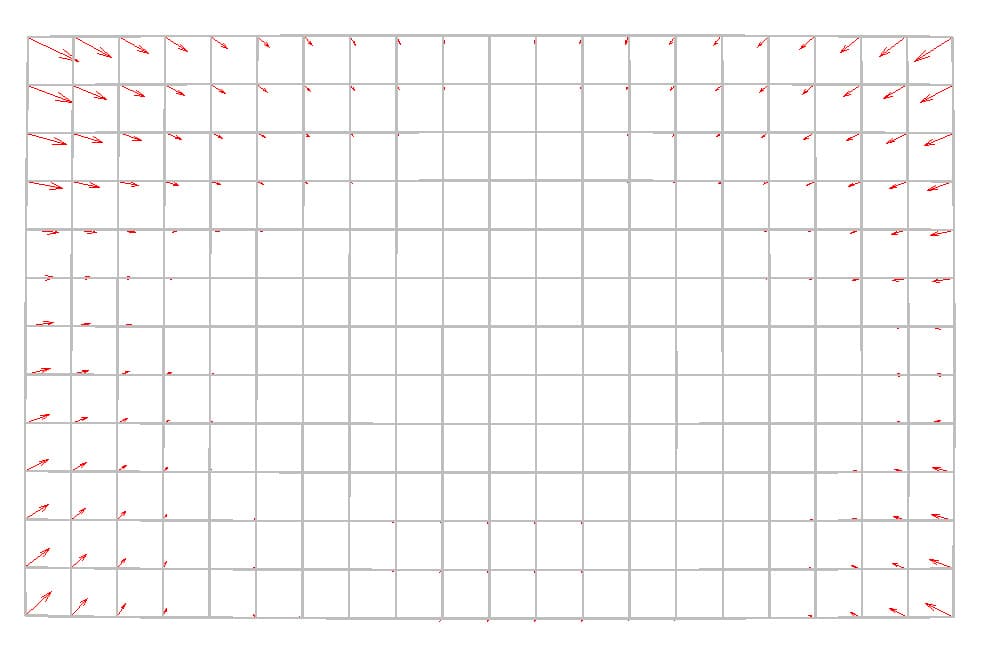

Meike MK 50mm F1.7: Curvilinear distortion

Examination of our chart tests reveals mild barrel distortion, and with the lens having no electronics, it can’t be corrected in-camera. Most of the time it won’t be a problem pictorially, but it’s easy enough to neutralise in raw processing when necessary. I found that a value of +3 applied to the Distortion slider found in Adobe Camera Raw’s Lens Corrections tab did the trick.

Meike MK 50mm F1.7 Distortion. SMIA TV = -0.7%

Meike MK 50mm F1.7: Verdict

Meike’s 50mm f/1.7 is a curious beast whose imaging characteristics take some time to unravel. Its compact size, all-metal barrel and simple operation all appeal, but with its peculiar combination of aberrations, optically it doesn’t behave quite as we’d expect from a 50mm prime.

As a result, Sony shooters desiring biting cross-frame sharpness would get better results from the FE 50mm F1.8, while Canon EOS R and Nikon Z-series owners would be better off using the firms’ respective 50mm f/1.8 SLR lenses via mount converters.

Sony Alpha 7 II, Meike MK 50mm F1.7, 1/60sec at f/8, ISO 125

On the other hand, if you’re primarily interested in getting a fast prime to shoot at large apertures for selective-focus work, the Meike will reward you with lovely-looking images. If this is the sort of photography you do, and you can live with manual focus, the MK 50mm f/1.7 could be a characterful addition to your lens arsenal.

Meike MK 50mm F1.7 specifications