This image by Turi Calafato recently triumphed in the Sony World Photography Awards Mobile category, separate from the main competition

Ever since smartphones became everyday, carry-anywhere items, using them to take pictures has turned into an extremely popular activity.

Mobile phones have long been the most popular cameras on image-sharing sites such as Flickr, leaving even the most popular compact brands from Nikon or Canon far behind. The trend has also pushed the massive growth of mobile-specific image-sharing apps and services, such as EyeEm, VSCO Cam and Instagram. In 2012, Instagram was bought by Facebook for an incredible $1 billion, and with 200 million users it is now more popular than Twitter.

This shows that smartphones have provided access to photography to a much larger group of people than any other new camera technology in history, and the term ‘mobile photography’, although coined only fairly recently, has already made it into our everyday vocabulary. That said, I don’t always agree with how the mobile photography community is using the term to set itself apart artistically and creatively from the rest of the photo community.

There are mobile photography exhibitions, meet-ups and competitions, but does it really make sense to categorise images by the type of camera they were taken with rather than the subject? I don’t think so. A photograph is a photograph and should be judged by its framing and composition, its visual appeal in general or the story it tells, but not by the equipment it was captured with.

As you might imagine, I frequently talk about mobile photography myself, but it tends to be in a technology context, in a very similar way to how you would talk about 35mm or medium-format photography. There is no doubt a smartphone is in many ways different to a DSLR, but in terms of image sensor size, manual settings, the ability to capture raw images and other features, modern smartphones are actually pretty close to consumer-level digital compact cameras. Likewise, many digital cameras offer at least some built-in filter effects and, of course, most of the processing effects available through smartphone apps can be created on desktop or laptop computers using appropriate imaging software packages.

So in my opinion, there aren’t actually too many good reasons to try to establish photography with a smartphone as a completely separate art form. It seemed in the good old days of non-connected imaging that people cared more about the picture and less about the device it was captured with. Let’s try to keep it that way.

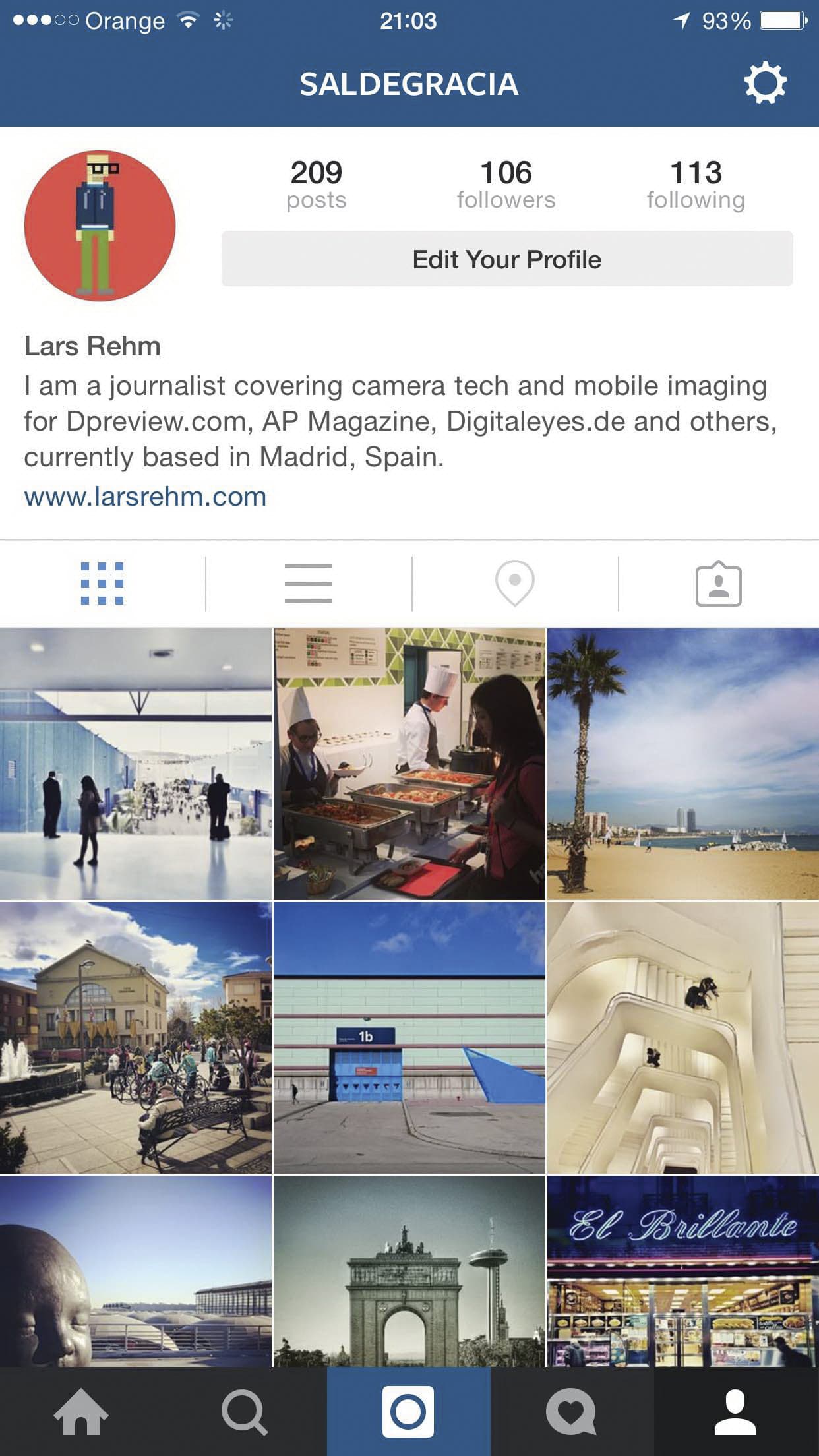

Lars Rehm is a freelance photographer and writer, contributing to publications in the US, UK and Germany. In his former role as part of DPReview’s testing team, he shot with countless digital cameras of all shapes and sizes, but nowadays he captures most of his images with a smartphone. Visit www.larsrehm.com or follow him on Twitter @larsrehm