Back in the summer of 2001, Nikon launched the FM3A, its final manual-focus film SLR. John Gilbey looks back at its significance 20 years on, and his experience with using it

Nikon FM3A at a glance

£700 price when new, £500 second-hand price

- 35mm film SLR

- Nikon F mount

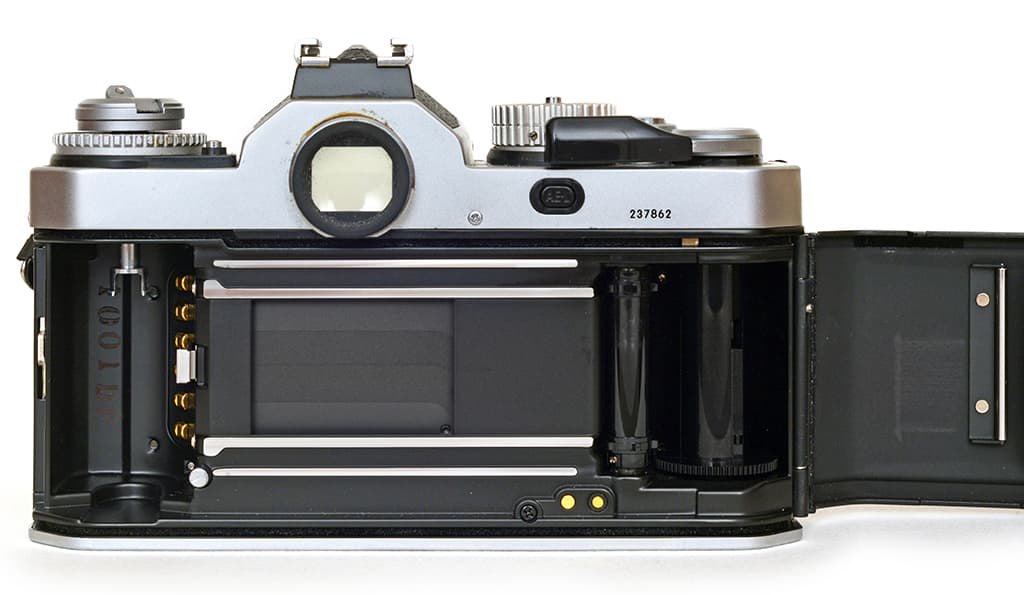

- Hybrid electro-mechanical shutter

- Shutter speeds 8 to 1/4000sec

- DX coded or manual film speed setting

- Viewfinder magnification 0.83x

- Centre-weighted metering

- Uses two SR44/LR44 or one

- CR1/3N battery

The traditional form-factor of the 35mm single lens reflex (SLR) evolved in the 1950s and was subsequently refined over the next half century. For many folk during this period, the range of Nikon SLRs, from enthusiast, to semi-pro and professional, provided a ladder of increasing capability as their photographic journey progressed. In the semi-professional range, it seemed likely that the FM2n would be the end of the line for the all-metal, all-manual FM series of SLRs when it appeared in 1983.

The world was moving on, autofocus had arrived, manufacturing processes were increasingly relying on plastics as the basis for the camera body, and it would not be long before digital imaging was banging on the door of traditional photography.

It was a surprise to many when Nikon launched the FM3A in the summer of 2001, two years after the D1 digital SLR. With manual focus, all-metal construction, no built-in winder and a marked absence of liquid crystal displays, it seemed to encompass everything that the SLR manufacturers were trying to leave behind at the time. It looked retro, even old-fashioned, and not a few photographers at the time scratched their heads and wondered who and what the enigmatic FM3A was for.

Pairing the body as a kit with a new 45mm f/2.8 pancake lens, often presented in a slightly garish silver finish, only added to the confusion. Was this a sensible camera choice for the working photographer or was it merely a rich man’s toy? Either way, it was short-lived, with production ceasing in 2006 after a very limited run.

I bought my own Nikon FM3A second-hand more than a decade ago, at a time when there was a significant lack of demand for film cameras in the marketplace. Interest in well-specified manual cameras is now much higher and I certainly could not afford to buy an FM3A today, as they are being snapped up at eye-watering prices by newly engaged film photographers and, perhaps inevitably, collectors.

Twenty years after its launch, in a digital world where retro chic is an industry in itself, the FM3A is rightly taking its place as a modern classic in the pantheon of camera history.

Nikon FM3A Design and handling

Pick up a Nikon FM3A after using a full-frame DSLR and you immediately get the sense of a compact, familiar, well-designed camera. Mine usually travels with a Nikkor 50mm f/1.8 AI lens attached. I bought it as a body-only deal and never bothered trying the matching 45mm pancake lens, based as it was on an old four-element Tessar design.

The 50mm combination is nicely balanced, fits well in my hands and is light enough to hike around with all day. The FM3A came in a choice of black or chrome finish, with a ‘pre-rubber-grip’ finish of artificial leather providing a useful tactile feel to the body and offering some protection to the prism housing. The lack of rubber body covering eliminates the risk of the camera developing the annoying stickiness that haunts some Nikons from this era.

All the controls are well placed, positive and responsive, having been designed with scrupulous attention to detail and engineered with a degree of excellence. The design philosophy seems to be that of reliability, practicality and usability, based on the evolution of the type over many years, and there are some very nice touches.

The body is equipped to read DX codes on film cassettes, automatically transmitting the film sensitivity to the exposure meter, although this can also be manually set. The shutter can be fired remotely using a traditional screw-in cable on the shutter release, rather than a dedicated own-brand connector or infrared release.

There is even a lever to allow the camera to take multiple exposures, which opens up another world of creative opportunities. If you miss having the film wound on automatically, you could always add an MD-12 motor drive, but the added weight and bulk rather negates the point of having a compact SLR in the first place.

The FM3A can be used either in automatic aperture priority mode or in manual with match-needle metering, giving a useful degree of flexibility. An impressive feature, and possibly unique for a camera that can operate in aperture priority, is that the shutter can fire at any selected speed even if there is no battery in the camera.

Most SLRs of this period only offer a single ‘emergency’ shutter speed in this eventuality, often around 1/90th of a second. The design and execution of this hybrid shutter – essentially mechanical and electronic shutter control systems combined into one – is remarkable, and a significant bonus for anyone who spends time in remote areas where batteries may be hard to find.

Put the FM3A up to your eye and you find that the viewfinder is big, bright and uncluttered. The screens are interchangeable, but the standard offering is an excellent matt screen with both microprism and split wedge focusing aids in the centre. The aperture of the AI or AI-S lens that is mounted on the camera can be read optically through a window at the top of the screen, a simple and effective solution.

To the left-hand side, the range of shutter speeds is shown, with red tabs indicating Automatic mode at the top and B at the bottom. In auto mode, a moving needle shows the selected shutter speed when you tap gently on the shutter release. With a manual shutter speed selected a blue tab indicates the current speed, while the needle shows the recommended exposure.

In Automatic mode, the shutter is specified to give a maximum of 8 seconds exposure time – but as with some other Nikon SLRs, this can run much longer in reality and enables some striking night-time images. The meter needle doubles as the battery check: the needle should only drop back down 15 seconds after you take your finger off the shutter release, otherwise the batteries need replacing. If you tap the shutter release and the needle doesn’t move at all, you’ve probably tripped over one of the built-in safety features.

In order for the shutter release to work, and the meter to turn on, the film advance lever needs to be in the ‘stand-off’ position. With the lever flush with the camera body the FM3A will refuse to take a picture – which may save you the occasional wasted shot, but will sometimes make you miss one!

The metering system is a traditional centre-weighted affair, where 60% of the weighting is given to a circle of 12mm diameter in the middle of the frame, which is helpfully marked on the standard screen. While not as sophisticated as the matrix metering systems that Nikon was already including in other SLRs at the time, this gives robust and reliable results in most conditions, although it can be fooled by backlit situations.

To account for this, the usual exposure compensation dial is available around the rewind crank offering an adjustment of between -2 and +2 stops. Alternatively, an exposure lock button is provided just below the film advance lever, which allows you to roam around the subject and then recompose the image while keeping the preferred exposure. At any rate, you always carry a handheld meter… Don’t you?

Flash is accommodated with a Nikon dedicated hot shoe and a standard PC coaxial connector. The TTL flash system supported is the predecessor to the current Nikon system, but there are many, many old Speedlight units available cheaply on the second-hand market. For fill-in flash, a compensation button on the mirror box drops the flash output by one stop, and there is a ‘flash ready’ indicator at the top of the viewfinder.

Flash will synchronise at speeds up to 1/250th of a second, which is marked in red on the shutter speed dial as a reminder.

The shutter release itself has, for me, just the right degree of resistance, making it clear when you are moving beyond the ‘meter on’ halfway point and are about to fire the shutter.

The sound of the shutter firing and the movement of the mirror is relatively subtle for a film SLR, reinforcing the impression of the good design and engineering which went into the product. There is a mechanical self-timer in the usual place on the right-hand side of the front

panel, which gives a reassuringly retro buzz as it operates. The self-timer can be cancelled and reset if necessary.

In practical use

The Nikon FM3A is a well-designed and well-engineered camera that makes an excellent companion for a variety of photographic tasks. It is compact enough to go into your luggage as a second body if you are also shooting digital, but makes a very good stand-alone camera for travel photography in its own right, where the ability to operate without a battery really stands out against its peers.

Over the past decade I have used the FM3A for street photography, reportage, landscape, portraiture, concert photography and a variety of other roles. During this time, it has proved utterly reliable and has never let me down. It is small and discreet enough to use without being too conspicuous, and it is surprisingly quiet in operation.

With the huge range of Nikon AI and AI-S lenses available, it is easy to assemble a compact outfit that occupies a bag around the same size as a current mirrorless system. My standard set of lenses for the FM3A is a Nikon 50mm f/1.8 AI, a 28mm f/2.8 AI-S and a 135mm f/2.8 AI, which sometimes gets swapped out for an 80mm f/2 AI for portraits.

The compact size and lack of vibration is also a bonus when working with longer lenses, while the large size of the mirror means that there is no ‘cut-off’ of the image in the viewfinder as you get in some other SLRs. In addition, the focusing aids on the standard viewfinder screen work well down to apertures well beyond f/5.6 – so I can happily use it on my 600mm f/5.6 Nikkor AI when the need arises.

The elephant in the room has to be the current price on the second-hand market. While older, and simpler, mid-range manual Nikon film SLRs can be obtained for less than £100, the FM3A can command asking prices more than ten times that for a mint example.

The low production numbers, innovative features and overall retro charm seem to have attracted a large number of collectors to the marketplace. This is a pity, because the FM3A is a camera that deserves to be used rather than confined to a glass case.

If you can find one at anything like a reasonable price, snap it up, load it up with your favourite film and take it outside. Is it worth the extra cost? Yes. This is a very capable camera that has been thoughtfully composed, is technically sophisticated and won’t get in your way. It is, in short, a pleasure to use.

Nikon FM3A Pros

- Build quality and precision

- Big, bright viewfinder

- Excellent handling

- Works at all shutter speeds without a battery

- Interchangeable viewfinder screens

Nikon FM3A Cons

- Lack of matrix metering

- No mirror-up facility (use the self-timer)

- High price

Further reading