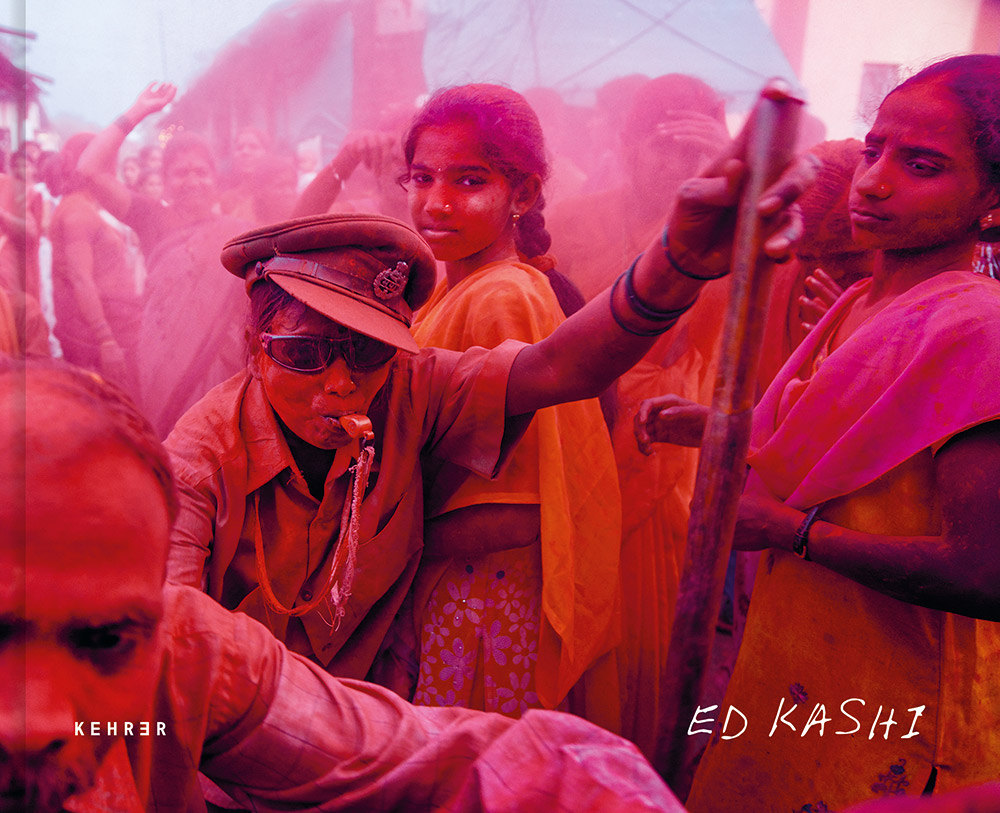

Steve Fairclough talks to US photojournalist Ed Kashi about his latest book, Abandoned Moments, a compilation of his work around the world

Ed Kashi is a much-travelled man. In a career spanning over 40 years, he has worked in more than 100 countries, capturing personal and commissioned projects for major publications. After originally wanting to be a writer, he changed direction when he was 18.

He reveals, ‘I happened to go to a university [Syracuse] that had a great photojournalism programme, so I vectored and said, “Well, what about photography?” Within two or three months of learning basic black & white darkroom skills, and learning about photographers like Gene Cunningham, and some of these greats that were working into their 90s, I was in hook, line and sinker.’

But it was another photographer’s book that truly had an impact on him. Kashi admits, ‘Mary Ellen Mark, the great American photographer, had come out with a book called Ward 81, which was this black & white study of a women’s mental institution in Oregon. I must have been 18 or 19 when I saw that book and I was like, “That’s what I want to be”. I wanted to do this kind of work and be involved in these sort of social and political issues and make these kinds of very gripping, soulful, black & white photographs. That really got me even more deeply passionate about that kind of photography.’

A big break

Like many before him, Kashi had early ambitions to be published by National Geographic magazine. Creating a body of interesting personal work was his route to get there. He explains, ‘I spent three years developing my project on the Protestant community in Northern Ireland and, after producing that, I was then able to break through to National Geographic. If you want to work for that magazine you need to show you can create a visual narrative and that you understand how to use the visual language of photography to create a coherent body of images.’

In 1991 Kashi self-published a book, No Surrender: The Protestants. The next time he went to National Geographic, Tom Kennedy, the magazine’s then director of photography, ‘was able to see in me something worth investing in’.

Kashi’s first project for the magazine was a story he pitched about the Kurds. He reveals, ‘I learned about the Kurdish cause in a café in Derry. I was meeting with a British painter who was married to a Kurdish woman. In many ways my first personal documentary project, on the Protestant community in Northern Ireland, is what took me over the top for magazine editors. I was starting to make images that made me excited.’

Photographic observation

In his latest book, Abandoned Moments: A Love Letter to Photography, Kashi riffs on various topics. These include the admission, ‘I stumbled upon a method of photographic observation, in which geometry, mood, emotion, and possibility – the instant – unite to create something new but unintended. I call this the Abandoned Moment; a concept that has run through my photographic approach for over 40 years.’

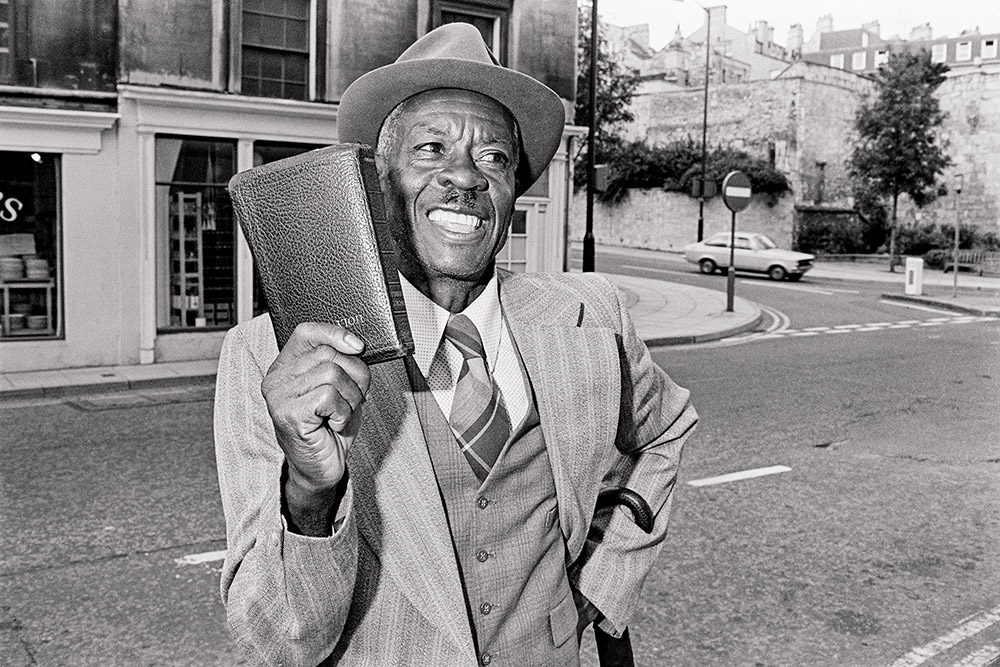

I ask Kashi how he stumbled on this method. He explains, ‘In 1977 I was a photo student in Bath, England. I didn’t know what I was doing with photography. I was just beginning, but I was messing around with flash on-camera. I was with a buddy in Bath and this Jamaican preacher kind of came up to us. He was dressed really well and he held up a bible, upside down, and started to preach. I made this picture, just “popped” him with a flash and I was using Plus-X film, which was kind of very rich.’

He continues, ‘I looked at that image and it was kind of an “a-ha” moment for me and my little creative processes. Wow! The flash and the texture and the depth and the movement – and yet I realised that when I made that picture, I didn’t know what I was doing.

It really was the sort of inverse of the decisive moment, where it’s almost like on a geometric and scientific level that you’ve captured a moment that has a sort of perfection. In this case, before I could understand how to articulate it, there was something that was born out of that moment and out of that image.’

Experimentation

Kashi further developed this method of shooting – experimenting with flash, slow shutter speeds and shooting from the hip – and, while it was not always the best approach for magazine publications, it did prove useful in various scenarios.

He reveals, ‘Over the ensuing decades this sort of one approach to photography that I had learned became integrated into my overall approach as a photojournalist. It served me as I started to work more in conflict zones or areas with civil unrest – a place like Nigeria where,

if I bring the camera up to my eye, I might as well hold a gun in my hand.

There’s something very visceral about this approach. As a 35mm dedicated photographer, it was really about flowing with reality. It’s a very freeing way of working as opposed to where, most of the time, I’m so focused on making sure that everything is perfect in the frame.’

Hitting the road

Within the Abandoned Moments book Kashi remarks he had to ‘hit the road to get comfortable’, so I ask him what this means. He replies, ‘This was earlier on in my life and my career. I had to sort of dive into the chaos of the world and confront that. When I look back at my childhood, no one would ever have earmarked me for doing what I ended up doing, which was working in over 100 countries… all that stuff that comes with it because I was a kid whose parents wouldn’t even let me go camping with the boy scouts – they were so afraid.’

Bonny Island, Niger Delta, 2004. Children play in the polluted waters of Bonny Island in the Niger Delta, where the Nigerian Liquefied Natural Gas plant is located

He adds, ‘I grew up in a very small world outside of New York City. As my love and commitment to photography grew as a young man I was confronted with a certain inherent shyness. I didn’t reach the age of 21 confident. I reached it with a lot of insecurities. Photography forced me, and therefore enabled me, to overcome those things because you have to go out in the world to do the work I do. You have to interface with people; you can’t be a wilting flower.’

Kashi’s latest book has been in the works for quite some time. He explains, ‘Roughly ten years ago I started to think more seriously about this idea of the “Abandoned Moment”. I was looking back at what I had done up to that point and, besides two or three specific forays into producing Abandoned Moments images, mostly in San Francisco, I started to realise I’d accumulated this other body of work that represented this very personal, specific approach to photography.

‘About that same time, within my studio, I started to collaborate, do image edits, design, layout. Then I was forcing myself to write and come up with some of these phrases. Over about a decade we moulded this book to a point where I then went to publishers and ultimately decided to go with Kehrer.’

The subtitle of the book is A Love Letter to Photography… Kashi reveals further about this, ‘It’s actually a love/struggle relationship because the love part is the doing. The love part is that I go out in the world with this recording device and I get to see things, to learn, to speak to people, to witness and then the craftmanship and the joy of creating an image.

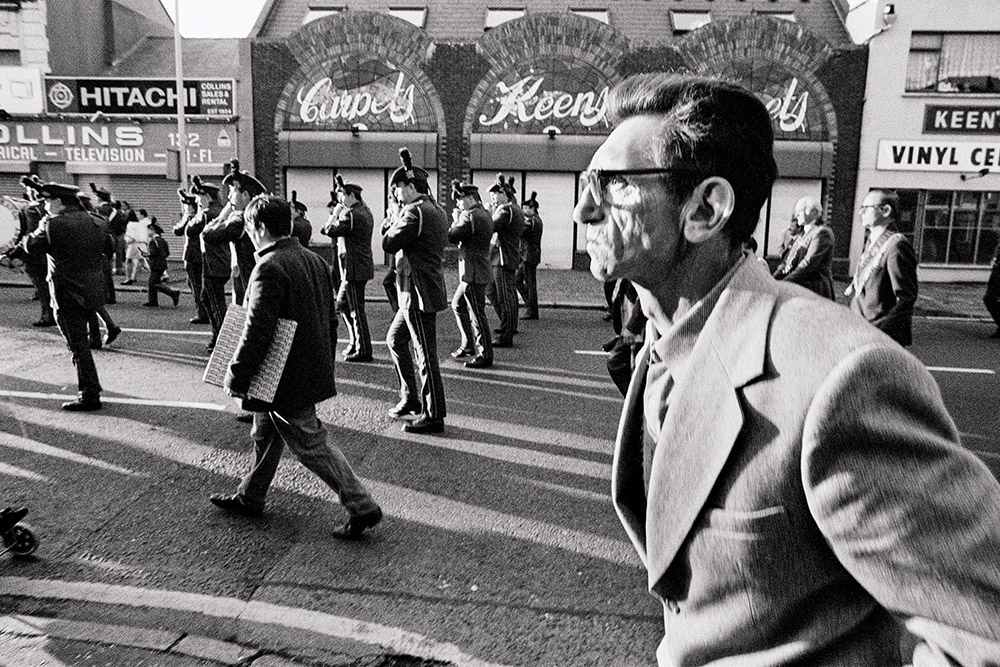

Belfast, Northern Ireland, 1989. A Loyalist parade marches through the Protestant heartland of East Belfast

Light and composition and texture and colour – all those things are inherently exciting to me. They make me feel alive. But the negative part is the business part. Even after all these years, there’s still this crappy part where you have to sell yourself. To some degree I’ve become immune to that, but not as much as I’d like because, ultimately, I want to be able to enjoy this genuine love I have for this craft and all it brings to my life.’

Photo ninja

When it comes to kit, Kashi keeps it simple. Describing himself as a loyal Canon user since 1977, he currently uses an EOS 5D Mark IV alongside Canon video equipment. He also works with mirrorless Fujifilm cameras. He says, ‘The X-T3 is a beautiful camera. I call it the poor man’s Leica. It’s just beautiful – the sensors on those Fuji cameras are really wonderful.’

He adds, ‘In this book, there are images created by Canon SLRs, by Leica M6s, by digital Canon cameras. I like to work light. At this point, now, with my work it’s generally one camera, one lens and a belt with two or three pouches, so I’m basically like a photo ninja. I have everything I need but I can also move, run, climb, duck, hop in and out of cars and I can be very fluid physically because that’s how I like to work. I have everything I need with a very simple setup like this.’

Kashi ends our chat by summing up Abandoned Moments: ‘What I’m trying to do is to de-contextualise the work of a photojournalist into a wholly new thing. The idea is that it’s a different or unusual approach to how journalistic photographers look back at their work. This is not meant to be a retrospective of my work because a retrospective of my career would have to involve experimental films, short documentary work, photo essays and so on.’

He closes, ‘This [book] is really meant to be a one-off – like a riff on one of the many ways that photography continues to be unique and magical. Those are the points that I hope are expressed. But it’s not to debunk the Decisive Moment by any means, because I still believe in that idea as a beautiful truth of photography.’

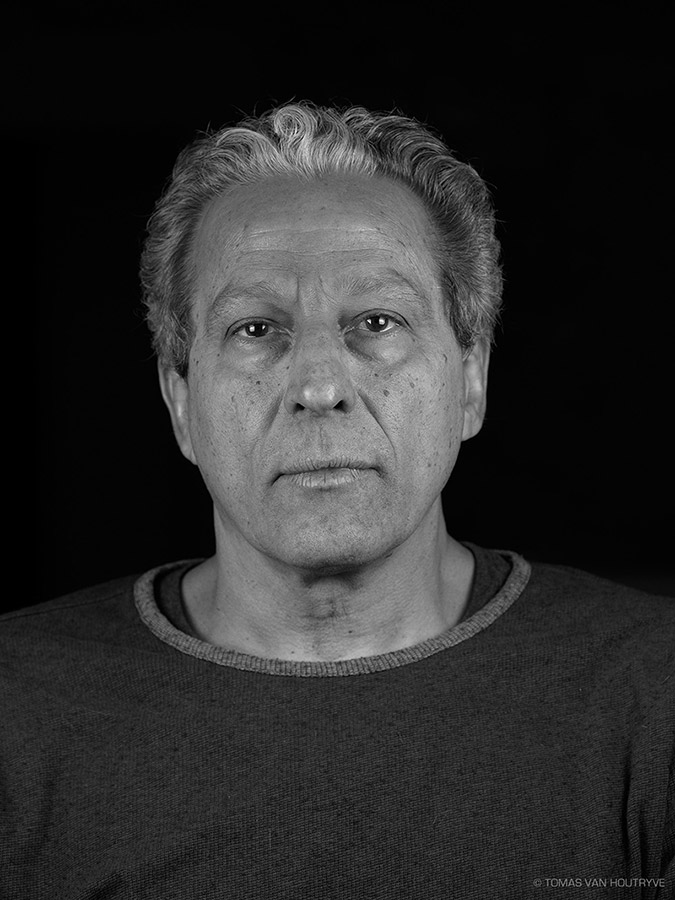

Ed Kashi

Born in 1957, Ed Kashi is a photojournalist, filmmaker, speaker and educator. As a member of VII Photo agency, Kashi has been recognised for his complex imagery and its compelling rendering of the human condition. His embracing of technology has led to creative social media projects for clients including National Geographic and MSNBC. Along with numerous awards from the likes of World Press Photo and POYi, Kashi’s work has been published and exhibited worldwide.

The book Abandoned Moments: A Love Letter to Photography, by Ed Kashi, is published by Kehrer Verlag (ISBN 978-3-96900-004-1), RRP €45.

Further reading:

Is it a bird or is it a plane? Capturing Dod Miller’s Birdmen

Fake news: how Jonas Bendiksen hoodwinked the photographic community with The Book of Veles