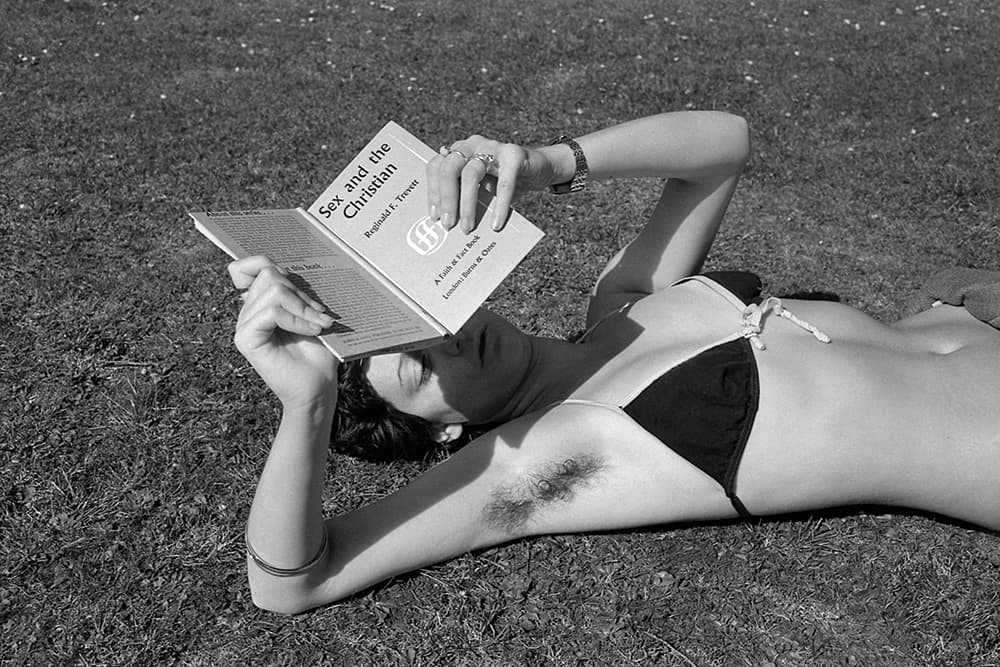

Summer days soon give way to the pressures of studying and endless revision for impending exams; this image also sums up the shifting attitudes of a generation soon to receive the keys to the world. All images by Paddy Summerfield

If the 1960s were a time of British ‘boy-done-good’ photographers exploding onto the glamorous international scene, then the 1970s seemed to move in a somewhat opposite direction. It was around this time that a series of photographers came to the fore who were undaunted by the idea of almost turning the camera inwards and creating a much more personal vision of the world around them.

This is perhaps largely a response to the numerous photographers from the USA, who demonstrated that deep beauty could be found in the everyday. William Eggleston, for example, who, with just a simple image of a light bulb on a red ceiling, showed budding photographers that if they open their eyes a little wider they could find photographic opportunities everywhere. Add to that list Robert Frank, Walker Evans and Edward Weston, and you begin to see how a young photographer may have been inspired to take a fresh, almost uncharted approach to photography.

Photographers undoubtedly became so much more aware of the camera in their hands. No longer did they have to slave to commercial media briefs to make images. They could actually just make images as a form of self-expression.

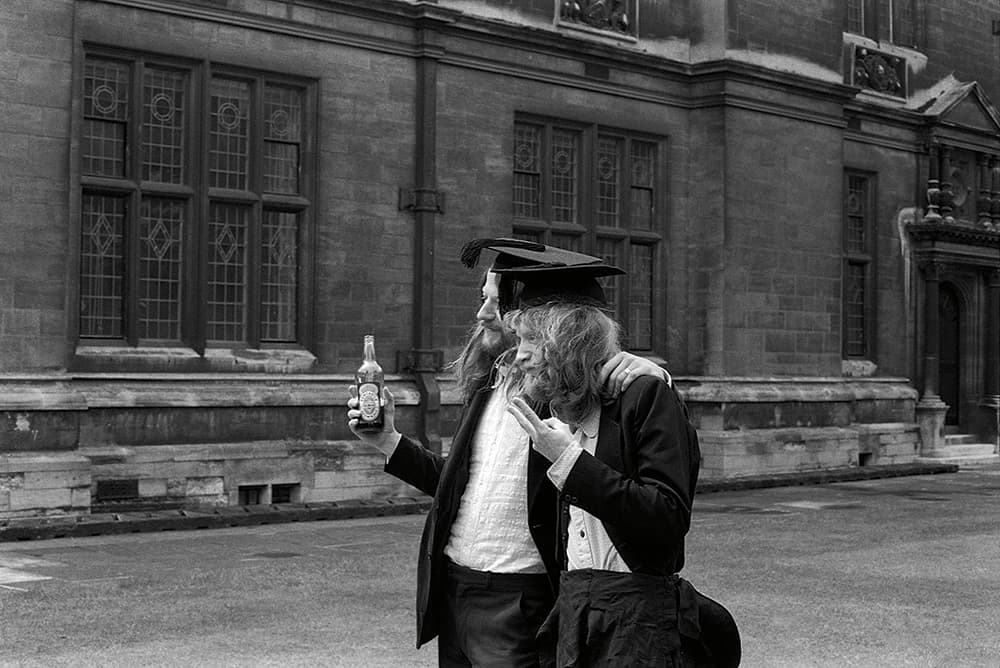

Two young lovers obscure their faces

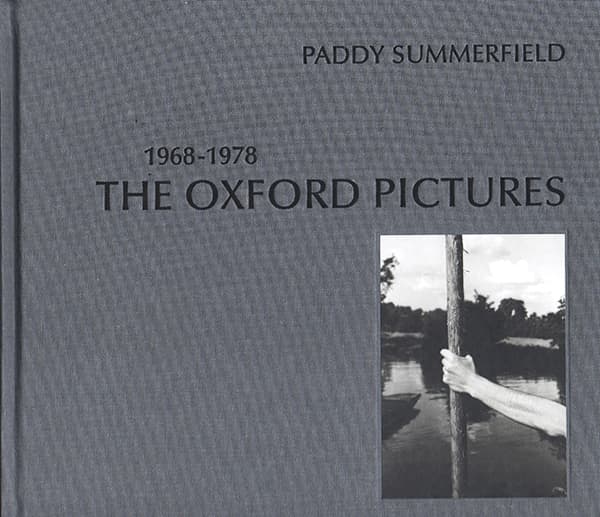

Between 1968 and 1978, Paddy Summerfield documented Oxford University students in the summer terms (or Trinity terms). These sun-drenched days began as one would expect – a little romance, drinking yourself into a stupor, lounging by the river and on the lawns – but as we can see from these images the pressures of education and impending adulthood meant those heady days soon gave way to endless studying and revision.

Paddy was still a young man himself when he made these images, no older in fact than the subjects he was shooting. He trained at the Guildford School of Art in the Photography and Film departments, and started working on these images when he was still a first-year student. As Paddy himself relates, the link between the photographer and his subjects is the degree to which uncertainty and loneliness seemed to dominate their lives. ‘Often, I sensed a loneliness in the students I photographed,’ says Paddy. ‘We were all lonely together.’

The everyday and familiar antics of students take on a strange poetic quality in Summerfield’s images

Growing pains

On the surface, perhaps, the images seem idyllic. They look as if they should be full of frivolity. This is, after all, Oxford University, the intellectual allotment for the elite. The glittering privilege we’ve come to expect from images with such subjects are strangely absent here, though. Instead, in image after image, we find a weird sort of alienation. Many of the pictures feature subjects with turned-away or obscured faces. In this sense there is nothing to latch onto–no eyes,–so we feel almost as alienated as the subjects themselves appear. Elements of doubt and melancholy infest the frames and it’s perhaps fair to say that here we can see the spare and minimalist influence of the European cinema of the day. Even in the scenes that seem to suggest some degree of reverie and debauchery, something doesn’t feel quite right. In these scenes, we witness the familiar costumes and rituals, but they seem almost staged, such is the sparse nature of Paddy’s every frame.

The collection is bookended by two portraits. In both, a look of awkwardness lies plastered on the young men’s faces. It’s here that we see the real tension that’s inherent in The Oxford Pictures. It’s the painful uncertainty of youth. They are making the tumultuous transition into adulthood, a world of careers, marriage, children and bills. The weight on their shoulders is crushing, no doubt exacerbated by the fact that they also have to contest with the degree of expectation afforded them by the label of ‘Oxford graduate’.

While the majority of us can in no way relate to the elite status these students enjoy (and Paddy does not expect you to), no matter what our background, we can all remember how frightening it was to stand on that precipice of adulthood and look over the edge to the dark unknown below.

SCORE: 5 out of 5

Published by: Dewi Lewis

Price: £30, 96 pages, hardback

ISBN: 978-1-90789-399-5