‘Jackpot’, 1961: Herzog’s work focuses on the everyday experiences of ordinary people.

There are always firsts – it’s just that in some fields there seem to be more firsts than others. That’s especially true of photography, a medium that has a history of ‘pioneers’ in single fields. Colour photography is a good example. The real pioneer of the medium seems to change depending on whom you ask (most people, perhaps rightly, would say William Eggleston) but let’s allow some space for another name: Fred Herzog.

Herzog’s work has much in common with William Eggleston, who eschewed big scenes in favour of the quotidian. It was through focusing on the everyday in the US that Eggleston was able to reveal the deeper truths of the world. Scenes of society in the macrocosm, rather than showing us nothing, showed us everything: race relations, urban alienation, gender politics and class distinctions.

Herzog’s images, taken in Canada, do much the same. ‘Content cannot be manufactured, in my opinion,’ Herzog says. ‘That which I can find is better than that which you can make. That which we find, the work and the use of the people out there, it’s natural, that’s what ordinary people do, that interests me.’

In his work, we’re shown a world we recognise, anachronistic as some of it may be, yet we relate to it. Despite slight shifts in social, cultural and technological parameters, the world now looks much the same as it did in the ’60s and ’70s.

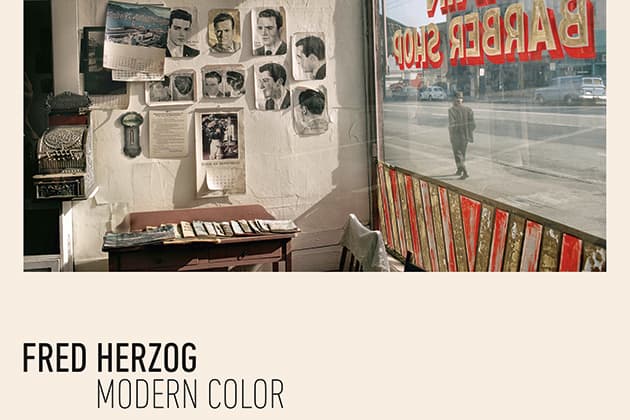

There’s defiance in the work of Herzog, whose images focused largely on the working class of Vancouver, Canada. Furthermore, his shots were taken using mostly Kodachrome slide film, meaning he was limited in terms of actually getting to exhibit his images in public. Add to this the fact that he was shooting in colour when the photography scene was still seeing the world in tones of black & white, and you have a photographer who was clearly shooting more for himself than for anyone else.

‘Boat Scrapers 1’, 1964: Through colour and form we find scenes that may be overlooked.

Developing images

Herzog started taking pictures in Germany in 1950 where, as part of a youth group who every summer went hiking in the Alps, he was given a Kodak Retina I camera. Those images, taken through a camera that possessed only a primitive peephole viewfinder, were lost some years later as Herzog travelled to Canada on a rust-bucket ship that apparently nearly sank. The boat took on water and all the images were destroyed by the corrosive salt water. However, once Herzog landed on dry land he continued taking pictures, the best of which were black & white and featured German immigrants pouring off the boat into Montreal.

A while later, Herzog worked as a medical photographer and also became a serious documentary photographer. He’d spend hours walking around the streets of Vancouver capturing the second-hand stores, signs and people. What was striking to Herzog at this time was that he was beginning to identify a genre that had perhaps not yet found its definition: street photography. Until that point, so few photographers had taken up the idea of simply touring the everyday streets and capturing what they saw. Certainly we can see examples of what appear to be street photography in older work – Walker Evans and Henri Cartier-Bresson, for example – but Herzog’s work was framed and defined specifically by this idea.

Eventually, Herzog began to discover the ease and convenience of colour photography. ‘First of all, when you do black & white, all you have is the basic resource – a negative. That needs a lot of dancing around the darkroom, and time, patience and energy. You should ideally be a man of leisure, an English gentleman. And a lot of English gentlemen did serious and beautiful photography… But I didn’t have time for that. That’s one reason I did colour slides. I’d get 36 slides back. Beautiful, finish.’

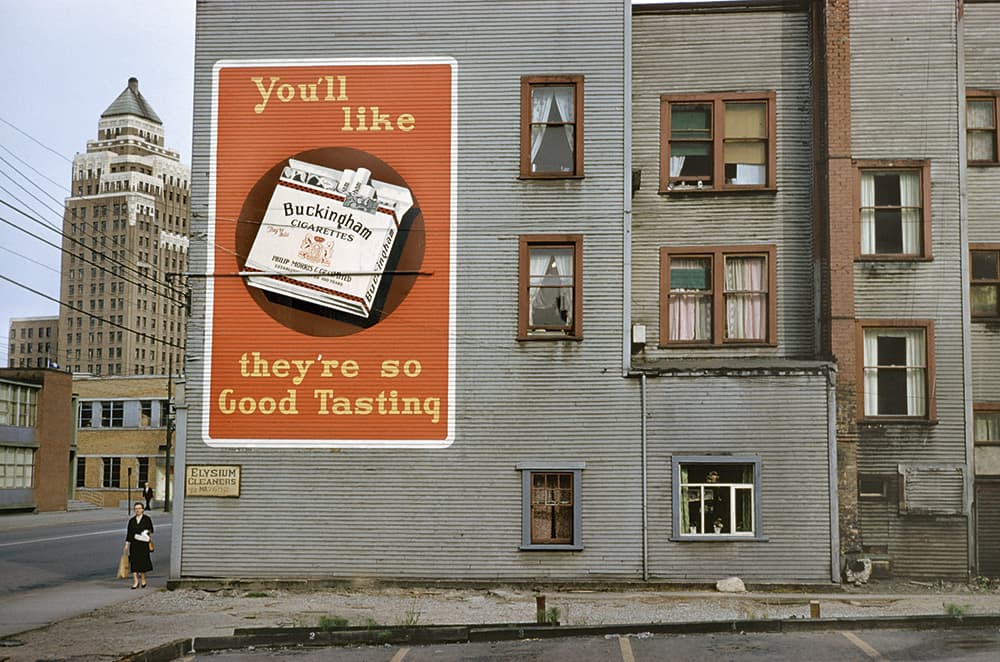

‘Elysium Cleaners’, 1958: An example of Herzog’s fascination with billboards and signs.

Colour and Herzog were a perfect marriage. Take a stroll through Herzog’s streets and you find a place awash with neon signs, Coca-Cola adverts, yellow light against thick shadow, vintage cars, billboards and the rest. It’s thanks to the lush tones of Kodachrome slide film that he was able to achieve this. It was the best film and most reliable development, although he had to wait an age for the results as he sent them to Palo Alto, California, or Rochester, New York.

It was worth the wait, it seems. Herzog knew that what he was doing was unique. He wanted to unpack the everyday and shock people with the familiar. But it has taken some years for his pioneering work to be recognised.

Ironically, considering his images were film through and through, it’s the world of digital that has finally brought his work to the world’s attention. Herzog was able to scan his images and present them as he’d always wanted them to be seen. If ever there was a case for the marriage of analogue and digital practices, this is it.

SCORE: 5 out of 5

Published by Hatje Cantz

Price £26.99, 320 pages, hardback

ISBN 978-3-77574-181-1