Oxford Tire Pile #4, Westley, California, USA, 1999. All images Edward Burtynsky

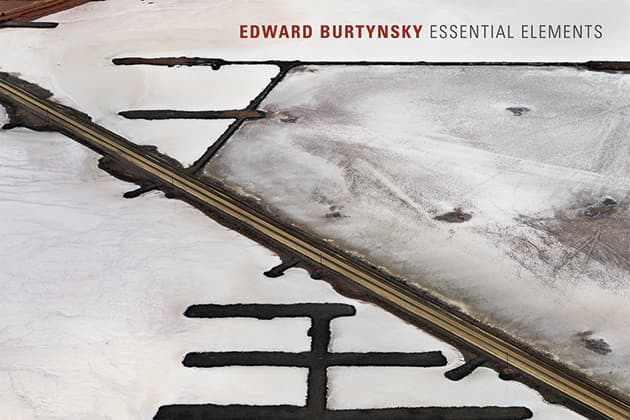

Edward Burtynsky belongs to a cadre of photographers who have made their name by creating large-scale and often awe-inspiring works that record manufactured landscapes and the results of humanity’s impact upon the world. Also in this group you’ll find Andreas Gursky, a German photographer notable for his ability to present scenes from an almost dizzying elevated vantage point, although, as he himself admits, it’s a method aided by digital manipulation. But where Gursky’s images are, as The New Yorker once said,’splashy’ and ‘entertaining’ Burtynsky’s work is more frank and sober in its approach. Distinct themes are present throughout, such as water, the oil industry, shipbuilding, mines and quarries. Each of these themes had distinct projects to represent them when they first appeared, but in Essential Elements we find that each of these projects has been reproduced together to create a flowing narrative. As a collection, the book treats Burtynsky’s work as a whole. Quite incredibly, it’s also the first time Burtynsky has been the subject of a career-overview book.

While many of Burtynsky’s images are a beautiful treat to behold (there’s around four decades worth of work to see, including previously unpublished images), a more clear-headed approach reveals a scarred and tortured landscape. The collection is timely considering our recent inauguration into the so-called Anthropocene epoch – a geological period that carries clear evidence of man’s impact on the environmental conditions of Earth.

Owens Lake #5, California, USA, 2009

Some of the landscapes look like the remnants of an abandoned civilisation. That’s the key to Burtynsky’s images – scale. If you were to walk through these locations on foot, it would be difficult to get a sense of them. But Burtynsky goes one step further by using elevated platforms and topography (and more recently, aviation), and through his camera and sizeable prints, he is able to deliver images that reveal the breadth and depth of the landscapes. This is why they feel alien. Rarely do we see sights like this through our own eyes. Rarely do we have the opportunity to absorb the sheer scale of our impact on the earth. Burtynsky has categorised his work as standing in contrast to Henri Cartier-Bresson’s ‘decisive moment’. Instead, what we have is the ‘contemplative moment’ – images that require time and thought to truly absorb what it is we’re seeing.

Documenting the hyperreal

The majority of Burtynsky’s work taken up until 2003 was captured with a large- format Linhof field camera and 4x5in film. However, in recent years Burtynsky has shot a lot of work from the air using helicopters and fixed-wing aircraft, meaning that he has been required to switch to digital. The Linhof had to be shot with a narrow aperture, which meant slower shutter speeds – a nightmare when the vibration of aviation is shaking you all over the place. But the switch to high resolution does something quite distinct. The textures and colours are somewhat elevated. They are unique and hyperreal, and in that sense they feel incredibly contemporary. As the world has moved on, so has Burtynsky’s approach to image-making. It fits perfectly. Despite the aesthetic contrasts, Burtynsky’s work could potentially be seen as a cousin to that of Sebastião Salgado. Together, both photographers tell a story of the journey of humankind and its impact upon the world.

Despite the fact that both their works have been captured over a period of decades, they are both notable for their ability to capture our most modern concerns: things such as migration/immigration, displacement, globalised economy, climate change, oil, natural resources, warfare, and so on. As with Salgado’s images, it would be easy to adopt a stringent pessimism and hopelessness. But beyond that, there is a slither of optimism. It’s just something you need to really look for in Burtynsky’s work. His aim is not to make us feel bad, but concerned. His aim is to highlight and inspire. That’s why these images are so detailed and huge. Like the best photography, they grab your attention first and then force you to ask questions. It’s a call to arms, not physically, obviously, but mentally and emotionally. And in that respect they are pretty effective.

Burtynsky’s images force us to look upon our work as a rapacious species and ask ‘Was it worth it?’ He doesn’t offer solutions, but it’s not his job to. That’s up to us as the audience.

Dam #6, Three Gorges Dam Project, Yangtze River, China, 2005

SCORE: 5 out of 5

Published by: Thames & Hudson

Price: £45, 202 pages, hardback

ISBN: 978-0- 50054-461-7