If ever there was a Renaissance man, it’s Art Wolfe. Here is a man who has his fingers in a number of pies, including photography, conservation, education and journalism. But it’s his photography that has garnered him worldwide attention. His approach is similar to those photographers of wildlife and the natural world – such as Nick Brandt and Tim Laman, winner of the 2016 Wildlife Photographer of the Year competition – who seek to raise awareness and help to preserve those spaces and species that may soon vanish from the Earth.

‘I think the relationship between conservation and photography got a big boost when the photo of Earth from the Apollo 17 spacecraft was published in the early 1970s,’ says Wolfe. ‘This view of the planet, called “The Blue Marble” [taken at around five hours and six minutes after launch], became a rallying cry for environmentalism. With that in mind, my photos have been used to protect the Alaskan Arctic, Canadian rivers and myriad other areas. As a Fellow of the International League of Conservation Photographers (iLCP), one of the goals of photography is to show the beauty of Earth and the need for conservation.’

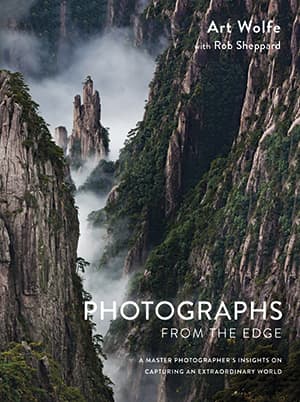

Huangshan, Anhui Province, China, October 2008. Canon EOS-1Ds Mark III, 70-200mm +1.4x converter, 1/13sec at f/14, ISO 100

All that considered, it’s always good to see a new book from Art Wolfe hitting the shelves. Photographs from the Edge (co-authored with writer and photographer Rob Sheppard) is the latest. Published by Amphoto, the tome is a visual record of Wolfe’s journey through life and a generous account of how he sees the world.

‘Many of my books tend to be large photo compendiums with little text,’ says Wolfe, referring to such volumes as Earth is my Witness (2014) and Migrations: Wildlife in Motion (published earlier this year). ‘I tend to let the photos do the talking,’ says Wolfe. ‘However, over the years I have found the brief photo notes sections at the back of these volumes to be very popular. So was born Photographs from the Edge. It’s also a sort of timeline of my life, arranged as it is by photo date – it really drives home the peripatetic nature of my profession.’

Spiritual Journey, Ganges River, Uttar Pradesh, India, January 2001. Canon EOS 3, 17-35mm,1sec at f/22, Fujichrome Velvia

There’s something bittersweet about Photographs from the Edge. There’s nostalgia, particularly in the depth of detail as Wolfe relates the story behind each of the images. Technical details, such as the cameras and lenses used, are there but sparse. ‘In my mind, photography is more about composition and training your eye,’ he says. ‘You can have the most expensive equipment in the world and still take bad photographs.’

Instead, what we gain from this book is Wolfe’s careful analysis about what makes each image work, such as in the arrangement of elements or the light. A good example is ‘Spiritual Horizon’, taken in 2001 at the Ganges River in Uttar Pradesh, India, which features a ‘pilgrim’ in a boat journeying towards the burning red orb of the rising sun (see above). For the more kit-minded, Wolfe used a polariser to darken the water, plus a graduated neutral-density filter lined up with the horizon to balance the exposure of the sky.

‘I really enjoy working the margins of the day, before and during sunrise and sunset,’ says Wolfe. ‘The low light softens harsh edges and even the most mundane scene looks like a painting. There’s a brief moment of transition during which the sun transits the horizon, but often you’ll have longer periods before and after the event where the landscape is bathed in beautiful light. The further you travel from the equator, the more time you will have in these ideal conditions – all the way to the poles where you can photograph nearly all day with the sun never quite leaving the horizon.

‘When the sun is higher, you hope for overcast conditions to block out the harsh rays of the sun and cast the landscape in even light. You can also hope for the best by perhaps using a 10-stop ND filter and a polariser.’

Les Aiguilles and Lac Blanc Savoy Alps, France, October 1995. Canon EOS-1N, 70-200mm, 1/4sec at f/16, Fujichrome Velvia

Without prejudice

For Wolfe, photography has always been an emotional experience – people are moved by the visual, perhaps more so than the written word. This is in no way to disparage the work of writers and poets but, in Wolfe’s opinion, humans love imagery, and when there’s a salient image that connects people to cultures they may not otherwise encounter, then that helps to bring people together on an emotional level.

‘It’s a powerful thing,’ says Wolfe. ‘For me, wildlife and landscape photography go hand in hand. Without one you wouldn’t have the other, but that’s my style of photography. Some people like to specialise in certain subjects, and some equipment is definitely more suitable to one genre or another, as are one’s reflexes and knowledge of natural history. As for me, I am a generalist – I like to say that I shoot without prejudice.’

Travelling to faraway lands has never been easier. As a result, we at AP are seeing more images taken in areas that were once inaccessible to photographers unless they had a National Geographic commission. But an aeroplane ticket is not enough to guarantee a set of good images. So how does a wet-behind-the-ears photographer make sure they approach a new location with confidence?

Simbu Dancers, Mount Hagen, Papua New Guinea, August 1994. Canon EOS-1N, 70-200mm, 1/30sec at f/16, Fujichrome Provia shot at ISO 200

‘Take a workshop from me!’ Wolfe declares. ‘That’ll loosen you up a little. But seriously, the best way to get comfortable and then get better is to practise. The beauty of shooting digitally is that results can be seen instantaneously. Whether it’s with your phone or a point-and- shoot, or a nice DSLR, everyone has to start somewhere. I tell people to set up lessons for themselves, set up goals. If you need a nudge, there are so many resources online now that make this very easy.

‘Research is of course key, as well,’ he continues. ‘One thing about travelling a lot is that I come into contact with a lot of other travellers, who give me recommendations, warnings and tips. I bring these ideas back to the office and together with my small staff we research to find what is best for my current projects. The web is an amazing resource, but it is only one aspect. Getting on the phone and talking to people on the ground is still extremely relevant.’

It’s also important to embrace something that can be considered a dirty word – failure. Wolfe, despite his incredible success, is not so arrogant as to think himself impervious.

‘Of course, I always remember the shots I didn’t get,’ says Wolfe, ‘but it gives me a reason to return and try again. I am nothing if not stubborn.’

For instance, on several occasions, he has travelled to Ladakh, India, with the aim of photographing snow leopards. In the 1990s, he had no luck at all, never getting closer than about four miles, despite several attempts. Then, in February 2014, he ‘just about’ succeeded. However, the image he captured was shot from a distance – not what he’d hoped for. ‘Needless to say, Ladakh is still on my travel list,’ he says.

Weddell seal, Antarctic Peninsula, Antarctica, November 2006. Canon EOS-1Ds Mark II,16-35mm, 1/125sec at f/11, ISO 640

Staying the course

Flicking through the pages of Photographs from the Edge, you’re struck by the sheer volume of work that Wolfe has produced throughout his career. As the photographer who has seemingly shot everything, how does he stay fresh and keep the spectre of inertia at bay?

‘At times, motivation is a huge challenge for any artist,’ says Wolfe. ‘Photography and travel are my stimulants of choice, along with coffee – I’m a good Seattleite that way. I get a huge charge out of being on the move, seeing new things and meeting new people.

‘I was lucky because my parents gave me a huge amount of leeway, but I think that is because they saw I had a focus even at a very young age. I was obsessed by wildlife and the outdoors, and sat with my mother as she learned to paint. Making art has always been the main goal of my life. As an artist, I feel inspired when I am inspiring other people. It’s a simple but extraordinary task to share this passion, which I do by teaching in the classroom and in the field. One thing art school drilled into me is never to be complacent. The day photography gets stale for me is the day I die!’

Kecak, Bali, Indonesia, March 2005. Canon EOS-1Ds Mark II, 24-70mm, 1/200sec at f/3.2, ISO 400

Hippopotamus amidst flamingos, April 2006

Lake Naivasha National Park, Kenya. Canon EOS-1Ds, 70-200mm, 1/2000sec at f/2.8, ISO 400

‘The edges of a photograph are critical to a composition,’ says Wolfe. ‘By using them to cut into a group such as these hundreds of pink flamingos, you force the viewer to study the pattern of the group rather than to look at the group as a whole. It also creates a visual impression of great numbers within the group. This image of flamingos and a hippo in an alkaline lake was actually taken from the air, while I was in an ultralight aircraft. The shot is unusual because of the hippo in the midst of the flamingos. It’s interesting to see how the birds give ample space to the hippo.’

Brown bear sow and cubs, July 2012

Lake Clark National Park, Alaska, USA. Canon EOS-1D X, 500mm, 1/320sec at f/18, ISO 1600

Lake Clark National Park, Alaska, USA. Canon EOS-1D X, 500mm, 1/320sec at f/18, ISO 1600

‘In the spring, brown bear mothers come out with their cubs to feed on the grass along the Alaska coastline at high tide,’ says Wolfe. ‘In this shot, the mother was in the tide flat munching grass while I photographed her. She was fully aware of my presence and comfortable with it. This area is one where fishermen have gone for years so bears understand that the humans present are not a threat. Moments before this picture was taken, the cubs were about 15-20 feet behind the mother, playing and chasing each other. Suddenly, the mother let out a bark and, instantaneously, the three cubs stopped playing and ran directly to her. I love the shot because I had never seen this behaviour before. Honestly, I’ve never seen three cubs stand with their paws right in alignment.’

Art Wolfe’s kit

Art Wolfe has used Canon cameras for years and old habits die hard. Currently, his favourite is a Canon EOS 5DS R, and his go-to lenses are a 70-200mm f/4L IS and 24-105mm f/4L IS for street photography. If he is on a wildlife shoot, he brings along a 200-400mm f/1.4L IS USM and a 1.4x converter.

Photographs from the Edge

Published by Amphoto, price £22.99.

ISBN 978-1-60774-781-9

Art Wolfe is considered to be one of the world’s leading nature photographers. He has published several books, won multiple awards and has been a leading figure in conservation. To see more of his work, visit his website at www.artwolfe.com.