Daniel is a fine-art photographer whose passion for conservation is evident in his images of our environment. His work – often in partnership with Greenpeace – has taken him to all seven continents. Daniel has received numerous awards, including two World Press Photo awards. He is a fellow of the International League of Conservation Photographers.

Three years ago, on 20 April 2010, British Petroleum’s Deepwater Horizon drilling rig, based around 40 miles south-east of the Louisiana coast in the US, exploded. The event claimed 11 lives and injured 16 others. What followed was the biggest oil spill the world has ever seen and one that devastated the Gulf of Mexico. The spill received a lot of media attention due to its scale and, as more and more information arrived, I became aware that this was a story that I needed to document.

In the past I have often described myself as a conservation photographer. Many people call me an activist and I suppose that’s really not far from the truth. I don’t believe in neutrality any more. I believe in fairness. I take a clear stand in the issues and it’s my hope that I can inspire people to become more aware of the need to conserve our planet’s resources. That was why I felt a strong desire to photograph the oil spill.

Once the initial oil fires had died, the media’s attention began to wane slightly. However, there then came reports of the oil leaking into the ocean. It was then that I received a call from Greenpeace, an organisation I had done some work with in previous projects. Naturally, they were incredibly concerned about the oil spill, so they asked me to go out to the Gulf of Mexico and see what I could do.

I spent around two months out there shooting with a Canon EOS 5D Mark II and 70-100mm lens. I was originally only supposed to be there for four days, but the story just kept getting bigger. The disaster saw around five million barrels’ worth of oil lost, but the US consumption of oil every day is 20 million barrels, which should give you an idea of the scale of the spill.

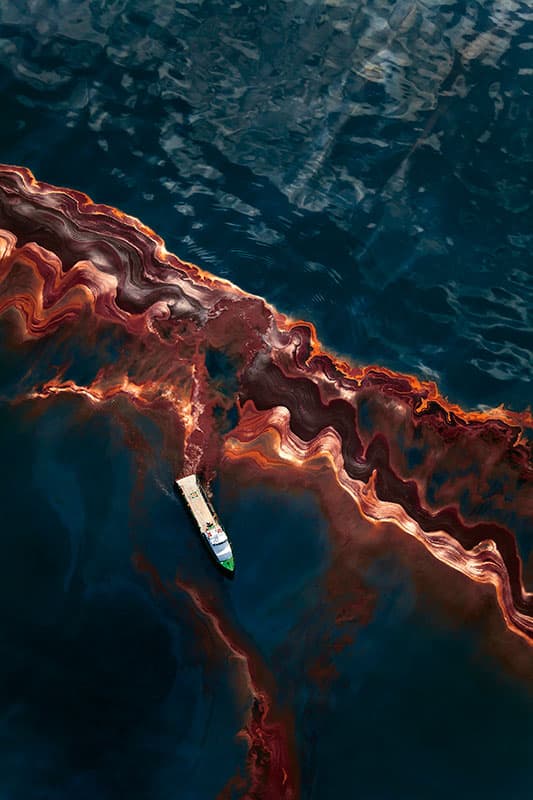

To get the shots I wanted, I flew around 3,000ft above the scene in a small four-seater floatplane. I sat next to the pilot and, as it was a high-wing aircraft, I was able to open the window and shoot down. Due to particular regulations that were put in place, we were not allowed to drop below 3,000ft. It was a restriction that served me well as it gave me a much wider angle of view and a great perspective.

My means of getting hold of a plane were incredibly unexpected. A well-off woman in Alabama started to fly environmental groups and journalists around the area so they could see the devastation first-hand. When Greenpeace called me and informed me that this woman was flying people around, I immediately got in contact and sent her some of my images from previous projects. She agreed to let me go out in the plane where I was able to achieve some initial shots. I showed her my results and she was so impressed that she gave the plane-hire company her credit card and said I was free to fly out as many times as I needed. It was a phenomenal gift.

The most interesting images happened within the first month of my trip. This very image was the moment I realised just how bad this disaster was. It was breathtaking. The spill happened around 40 or 50 miles away from the coast and for a long time the media circus that arrived in Mexico set up camp along the shoreline waiting for the oil to come to them. The only way you could really see the oil was to fly above it and look down. However, with currents, wind, weather and the dispersal techniques the clean-up teams were using, you were not always guaranteed a view even though the oil spread for thousands of miles.

When shooting this project I had to be incredibly adaptable, as the weather would really alter my working method. For example, if the water was choppy I knew I wouldn’t be able to get a shot like the one here because the image would be littered with lots of white caps (reflected light) on top of the waves. The oil can also sink in those kinds of conditions. It really kept me on my toes and forced me to think about every single frame.

When the pilot and I first found this scene, there was no boat around. I asked the pilot to fly around for a while and wait for a boat to come along. The boat was a crucial element as the vessel had to be there to introduce a sense of scale. With that boat in the frame, you truly see the scale of the disaster. If you look back through some of my previous projects, you’ll see that my work is relatively abstract so you’re not always sure what it is you’re looking at. However, the boat leaves you in no doubt.

The images that are most attractive to me are those that are somewhat abstract. I’ve had people approach me in art galleries when I’m exhibiting and say, ‘This is so beautiful. What is it?’ Once they’ve engaged with the image on an aesthetic level, I tell them what they’re seeing and it positions them in such a way that they can then engage with the topic.

There has often been a lot of criticism against war photography where photographers have created quite beautiful images of atrocities. Many feel that making aesthetic images of death or destruction renders the scene superficial and removes the urgency of the event and the message. I disagree. You have to grab a person’s attention. If you want a message to stick, you have to make sure your image is engaging.

I’m reaching a moment now – and this is 20 years into my career – where I’m almost tired of pointing the finger. Of course, people – in this case BP – must be held accountable, but it almost transcends that. I’m getting tired of doing these projects and making them political issues. The fact is, this is our planet. We all live here. I don’t care which party you vote for. We all want a healthy, sustainable environment for our children to grow up in.

Daniel Beltrá was talking to Oliver Atwell

To see more of Daniel’s images, visit www.danielbeltra.com. His book Spill, published by GOST, is available priced £30