Are hoax photographs harmless fun or harmful propaganda? Peter Dench has a rummage around the history of hoax photography to find out more and shares the best photo hoaxes below.

What is a hoax photograph?

What are photo hoaxes for, why are they done and what is the point of them? Can there be a legitimate place in photography for hoax pictures? Is a hoax photograph harmless, when does it become cheating and can it be a criminal act? I have questions. Writing for this magazine I’ve come across various photo hoaxes. Who can forget Jonas Bendiksen’s extraordinary, The Book of Veles, that hoodwinked the industry into thinking his documentary photographs of people from the eponymous town were legitimate?

Researching for an article on ethics in wildlife photography, I came across photographs of a frog riding a beetle, a snail riding a frog riding a turtle and five frogs riding a crocodile. These seemingly cute and funny hoax images were often cruel or deadly with subjects being glued, clamped, taped, wired, refrigerated, shaken or killed before being positioned for a photo. In 2010, The Natural History Museum, Wildlife Photographer of the Year winner, José Luis Rodriguez, was stripped of his £10,000 prize after judges found he was likely to have hired a tame Iberian wolf to stage the image. In 2016, a winning entry by Marcio Cabral was disqualified for featuring a stuffed anteater after it was decided it was ‘highly likely’ a taxidermy specimen. Aren’t these just high-level hoaxes? If they were NFTs I’d gamble they’d prove collectable.

Writing about the ‘Golden Age’ of photojournalism and iconic British weekly magazine, Picture Post, rumours persist that the darling of the magazine, Bill Brandt, was often liberal with the truth, using his family in some of his photographs dressed as east end gangsters. The controversy surrounding Robert Capa’s photograph of a falling soldier rumbles on. With one determined academic, José Manuel Susperregui, saying he has definitive proof that his legendary Spanish Civil War photograph was a fake. One of the first recognised documentarians of war, Roger Fenton, probably staged his image, Shadow of the Valley of Death. Moving cannonballs from the ditch onto the road in order to create a more dramatic image. Are these photo hoaxes or just using your nous to illustrate a story on deadline?

Photo hoax history

The definition of hoax is: something intended to deceive, hoodwink or defraud. Type ‘hoax’ into Thesaurus and you get: bamboozle, bluff, con, deceive, delude, dupe, fleece and fool among others. Type in ‘fake’ and hoax isn’t an option. Hoaxes in photography are as old as photography. According to the Guinness World Records, the first hoax photograph was: Self-Portrait as a Drowned Man (1840) by Frenchman, Hippolyte Bayard. The image shows Bayard slumped to one side in an act of protest for never receiving what he believed was his rightful credit for inventing photography. The process was instead attributed to competitors Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre and William Henry Fox Talbot.

77 years later, a series of photographs had the world believing there were fairies at the bottom of the garden when cousins Elsie Wright (16) and Frances Griffiths (9) made paper cutouts to create a series of images in the garden of a Cottingley village home. Photographic ‘experts’ examined the pictures and declared them genuine. Mediums claimed them as proof of the existence of the supernatural. Despite criticism by sceptics, the photos became among the most widely recognised in the world. Decades later, the girls finally admitted that their photos were fakes. Elsie drew the fairies on paper which were fixed to hat pins, stuck in the ground and photographed. They then got rid of the evidence as all good hoaxers should, drowning their Cottingley fairies in a brook.

Spoiler alert

A good hoax photo treads the line of believability. Trying to find out how it was done before it’s explained is part of the lure. The BigFoot film still at Bluff Creek in 1967 was a man named Bob in a costume. The 1934 photo published in the The Daily Mail of The Loch Ness Monster allegedly taken by British surgeon Colonel Robert Wilson, is a Woolworth’s toy submarine attached to a sculpted wooden head. George Edwards, a cruise boat operator on the loch, claimed his 2011 photo of Nessie’s hump had been verified by a team of US military monster experts when it was a fake fibreglass model created for a National Geographic documentary about the aquatic behemoth. George Adamski’s 1952 photo of a foreign spacecraft flying over his California home was cobbled together using a lamp, light bulbs and other bits and bobs.

For a 2022 Amateur Photographer magazine halloween special I took a full-spectrum ghost hunting camera into the bowels of London’s historic east end alleyways, desperately wanting to snap the deceased. I didn’t get as lucky as photographers Captain Provand and Indre Shira who captured on film, The Brown Lady of Raynham Hall, while on assignment for Country Life magazine in 1935. The chilling photograph has never been conclusively disproved. Sewage farmer and keen photographer Tony O’Rahilly took to his grave the technique behind his 1995 photograph of the Wem Ghost, a girl engulfed in flames as a building burned. Dr. Vernon Harrison, former president of the Royal Photographic Society analysed both the photo and negative and reported that he was satisfied that the picture had not been doctored.

Alleged Photo of Bigfoot. Photo shows what former rodeo rider Roger Patterson said is the American version of the Abominable Snowman. He said pictures of the creature, estimated at 7 1/2 feet tall, were taken northeast of Eureka, California. (Getty Images)

Propaganda

Hoax photography can be a powerful tool for political and military gain with despots and dictators leading the way. Supreme Commander in Chief of the Armed Forces of the Soviet Union, Joseph Stalin, understood the historical value of photographs and was prolific in removing traces of his enemies from them. When secret Police Official, Nikolai Yezhov fell out of Stalin’s favour, he wasn’t just executed but erased from photo-record by Stalin’s team of photo retouchers. Inspired by the photograph of American troops raising the flag at Iwo Jima, Yevgeny Khaldei’s iconic 1945 photo of soldiers raising the Soviet flag over Berlin’s Reichstag building was staged and then doctored.

Flying The Flag. Russian soldiers flying the Red Flag, made from table cloths, over the ruins of the Reichstag in Berlin. (Photo by Yevgeny Khaldei/Getty Images)

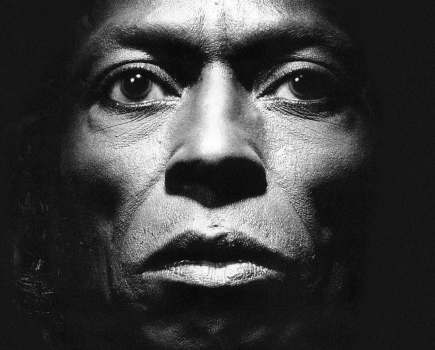

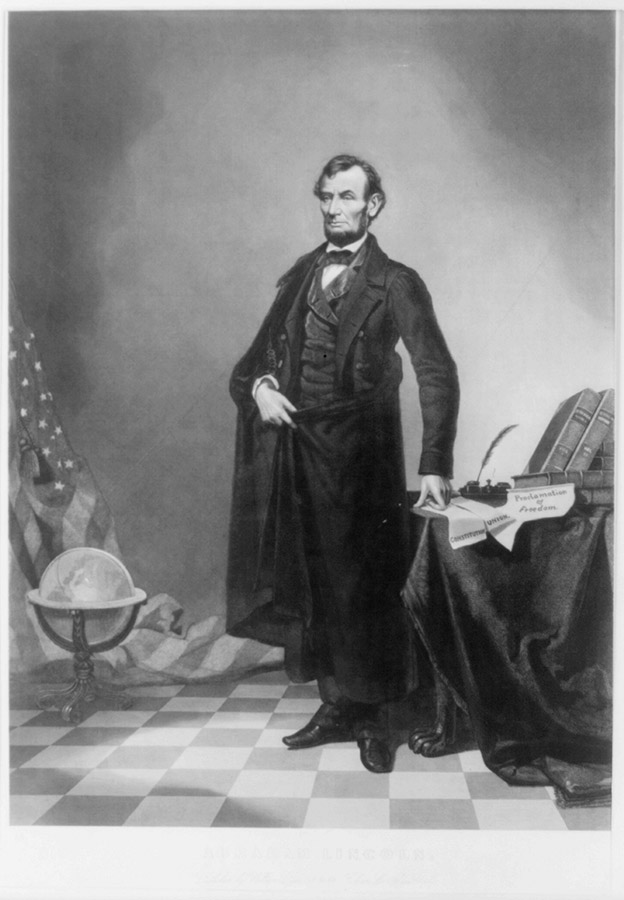

Covering up wasn’t the preserve of Communists. Adolf Hitler’s propaganda minister, Joseph Goebbels, was ironically removed from a photo of him and director Leni Riefenstahl in 1937. Benito Mussolini circulated a famous photograph of himself riding victorious on a horse after cropping out the handler holding the horse. Kim Jong-Un apparently applies Photoshop to make his ears look smaller. Further back in time, the iconic portrait of the U.S. President Abraham Lincoln is a composite of Lincoln’s head and the body of southern politician John Calhoun.

Photo hoaxes today

With the proliferation of affordable cameras, omnipresent phone cameras, the internet, social media and advances in AI, today is a hoaxers paradise and pranksters have not held back. I’ve lost days down the double-headed rabbit-hole of hoax online photographs. A noticeable difference is the online hoax doesn’t always carry on unexplained for decades, the revelation is part of the hoax: The photo of a lion strapped onto a machine to make the iconic MGM intro of a lion roaring is actually a photo of a lion being diagnosed at the vet’s office. The photograph of a magical destination is a combination of a photo of a rock in Thailand and a castle in Germany.

The head of Abraham Lincoln is superimposed on the figure and background of an earlier print by A.H. Ritchie showing John C. Calhoun, 1852.

Photographs of cyclists or photographers are dropped in front of stock images of grizzly bears in full attack mode. The moon and sun are plotted across skies appearing in perfect juxtapositions. Cloud formations and bird murmurations are manipulated into amusing shapes and endless cats sit in impossible positions. There are web pages dedicated to showcasing hoax images and others dedicated to disproving them. You’re probably not as good at spotting a hoax photograph as you may think. I consider myself a connoisseur of fakery and guessed 17 out of 25 correctly in Adobe’s Real or Photoshop test of observation and a respectable 5 out of 6 in the BBC’s Bitesize Fact or Fake.

Even before 2012 Hurricane Sandy hit US soil, doctored photos were circulating online. The misinformation was so acute to people who were vulnerable to danger that @GuardianUS urged people to use the hashtag #FakeSandy along with the photo link. The Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (Darpa), which develops technology for the U.S. military, is attempting to create a tool that will automatically detect the manipulation of images and videos and assess their integrity. Hany Farid, an American university professor who specialises in the analysis of digital images and the detection of manipulated images such as deepfakes is working as a researcher with DARPA. He is also co-founder along with Kevin Conner of image analysis firm Fourandsix, according to the BBC, they have licensed their tool izitru (is-it-true), to Darpa, which looks at how a file is packaged and helps determine if an image came directly from the camera.

Russia / Soviet Union: Josef Stalin walking with Vyacheslav Molotov (left) and Nikolai Yezhov (right), Moscow, 1937. (Photo by: Pictures From History/Universal Images Group via Getty Images)

How to spot a hoax

The path to spotting photo hoaxes can be long and winding: trust your instinct, if it’s too good to be true it probably is. Analyse the light, shadow and reflections in an image to see if they align with the laws of physics. Question if you’ve seen the image before. What are people doing, wearing and how are they behaving. If there’s a shark swimming in a flooded suburb, it’s probably a hoax. If the Daily Mail has published it, perhaps check with a reverse search search on tineye.com or check Snopes (formerly Urban Legends Reference Pages) a fact-checking website for sorting out myths and rumours on the Internet.

Arguably most of us enjoy a good photographic hoax. It should be in the spirit of a Sideshow Illusion Show: Olga the Headless Girl, Spidora (the head of an actual woman with the body of a giant spider) and the Girl in The Goldfish Bowl (no cats allowed) were unbelievable with just a chink of credibility that had crowds wondering what if, just maybe. They tickled the senses, raised the heart rate and a smile. Bayard’s hoax was a broadside at the establishment for no evident financial gain. George Edwards appropriation of Nessie’s hump was to boost business but forgivable. Francis and Elsie’s intentions were invigorating, the photos eventually making more than £20,00 at auction in 2018.

Mussolini Receiving The Islam Sword At Tripoli In Lybia On March 1937. (Photo by Keystone-France/Gamma-Keystone via Getty Images)

The gall of George Adamski’s UFO is to be applauded. Today artist and photographer Alison Jackson continues to titillate with her spoof documentary photographs of celebrities doing things we’d like to think they do. Perhaps when you next have a spare half day, rummage in the recycle bin. Find some thread, tape, grab your camera and see if you can make it into the great photo-hoax history book.

Featured image: A view of the Loch Ness Monster, near Inverness, Scotland, April 19, 1934. (Photo by Keystone/Getty Images)

Further reading:

Man on the Moon photo named most famous of all time

Fright night: ghost camera takes spooky London photowalk