Trudi employs a wide aperture and higher ISO to nail the dynamic live show of Stacie Collins & the Al-Mighty 3. Nikon D600, 14-24mm, 1/160sec at f/3.5, ISO 3200. © Trudi Knight

Kit list

- Full-frame SLR Workhorse full-frame SLRs such as the Nikon D750/810 and Canon EOS 5D Mark III/IV remain popular with gig photographers owing to their detailed raw files and superior high ISO performance, but higher-end mirrorless cameras are catching on too.

- Fast zoom lenses The standard lens combo for many gig photographers is a 24-70mm and 70-200mm f/2.8, but some prefer wider glass. ‘I use a 14-24mm f/2.8 wherever possible,’ says Knight. ‘I am always looking for interesting interactions between band members, and I like using a wideangle lens.’

- Camera harnesses You don’t want to miss a great shot as you are fumbling around changing lenses. Many seasoned pros will have two camera bodies attached to a harness – one body usually has a longer telephoto lens attached.

- Specialist lenses It’s not all about fast zooms. Leading rock photographer John McMurtrie sometimes uses fish-eye lenses for shots of both the band and crowd, for example. These tend to work better in bigger venues.

A lot of AP readers will be music fans, and photographing a gig or festival can be a great way of combining two passions. Sadly, however nice it would be to get a photo pass – right down in front of the band, with no beer-swilling giants spoiling your shot – you’re unlikely to get one for a major act just because you really like them and want to build your portfolio. A more realistic option is to build your skills by shooting less well-known bands, who are often eager for publicity images – and who knows, that less well-known band might become very well known one day.

While shooting a band in a smaller, friendlier venue can be a lot of fun, it’s also demanding. According to leading gig photographer Trudi Knight, the biggest challenge of shooting bands in smaller venues is uneven low lighting, or none at all. ‘I remember a small gig in Hoxton years ago where literally the only light reaching the band was from a fire exit sign above a door, and a street light outside,’ she explains. ‘Poor lighting is very common, and the first thing you will need to learn to overcome, along with cramped stages where there may be no angle or position in which your view isn’t blocked to some extent by stage furniture, like mics and monitors.’

No pit is not the pits

Generally Knight has found smaller/independent venues to be a lot more relaxed about cameras, and reckons that most venue security take their cue from the band’s instructions anyway. ‘I can’t think of many occasions in a less-than-200-capacity venue that I’ve encountered significant problems. I don’t leave it to chance though and will check in advance.’

So that’s good news, and what’s more, the lack of a dedicated ‘photographer’s pit’ found in bigger venues can actually be an advantage, Knight reckons. ‘The main pro is that no pit means that the show will be up close and personal, and you can get right in the middle of the action. No artificial barrier between the band and the audience usually makes for a better atmosphere, and there’s also a lot of potential for getting shots of good interaction between the two. The main con is that finding a good spot can be problematic, especially if the place is rammed and there’s not much scope for movement.’

As many readers will know, the use of flash is frowned upon at most concerts as it can be a distraction, so most gig photographers get by with fast, wide-aperture lenses and higher ISOs. Knight’s approach is typical. ‘I’m not scared of noise, and with the camera bodies I use now, I will happily shoot at ISO 6400 if it makes sense (though I always adjust ISO, aperture and shutter speed manually as I go). High ISO performance has improved drastically in the past decade, and noise reduction software has also come on in leaps and bounds.’ You also need to be comfortable taking control of autofocus and shutter speed.

‘I actually switched to back button AF a few years ago, as I found it a lot more logical – it takes away the frustration of accidentally refocusing at the wrong moment. With more active bands I like to be around the 1/160 mark if possible, though I can handhold down to 1/60th fairly comfortably if band members aren’t running around, or if I have something to steady myself against. If I’m going for a jump shot I will often also use panning if the shutter speed needs to be on the lower side, to try to retain sharpness where it’s most needed.’

Another big skill is preparation and anticipation, particularly when it comes to bagging those prized action shots. ‘In terms of being prepared, it’s imperative to learn to see the action coming and look for clues in body language, and this gets easier with experience. I always try to keep both eyes open when shooting as you can often catch sight of something good about to happen in your peripheral vision, be it a guitar spin, or a jump, or just a really nice bit of interaction between people on stage.’

Stay flexible – and polite

While Knight is full of useful advice, she reckons there is no ‘one size fits all’ approach for gig photography. ‘Part of the fun is finding yourself in a challenging situation and knowing how to pull something out of it that you’re happy with.’ That said, she reckons there are positive things you can do to give yourself the best chance of great shots from a gig or festival. ‘It pays to be personable – so build relationships and trust. Chatting to venue staff, and to the people you’re at the front with, is always a good thing, especially in venues with no pit – people in the audience are generally lovely once they realise you’re not going to interfere with their enjoyment of a gig, and will often help you to get the shots you want by swapping places or letting you into their spot for a minute.’

Patience is a virtue, too. ‘One of the great things about smaller venues is that there’s often no time restriction other than the length of a band’s set, and taking enough time to observe patterns of movement and lighting and figure out when the light is going to be in the right place or when someone is more likely to step away from their mic can make a huge difference to your results.’

It’s also important to know your camera settings inside out, otherwise you’ll waste time fumbling around in the dark and miss opportunities. ‘Never be afraid to experiment, either, whether it be with angle, positioning, or camera settings (but always shoot raw). Trial and error is a large part of learning gig photography, and in smaller venues without a three-song limit, you have the luxury of time.’

Finally, she urges all gig photographers to think about etiquette, for everyone’s sake. ‘So don’t leave the autofocus assist light on so it illuminates a performer’s face, don’t unnecessarily block people’s view or hog space, fail to suppress on-camera flash, and generally act like you’re more important

than the people who’ve paid to see the band!’

Trudi Knight

Trudi Knight is a well-known international gig photographer based in London, whose photos have been featured in the artwork for 30 CD/DVD/EP releases to date, as well as extensively in band merchandising. See www.bandsonstage.co.uk.

Shona Cutt got into position early for this trademark jump and used her SLR’s burst mode. Canon EOS 550D, 24-70mm, 1/320sec at f/2.8, ISO 1600. © Shona Cutt

Exposure advice

Many of Knight’s points are echoed by Shona Cutt, another talented gig photographer who does a lot of work in smaller venues. Cutt also gets around the lighting challenges by keeping her lens apertures wide and her ISO up. ‘Noise is not so much of a worry, particularly as grain can be good for a cool rock-and- roll shot. Clients don’t tend to worry about noise so much if shots are only going on social media either.’

Cutt is also keen to avoid blown-out highlights on band members or instruments, another rookie error. ‘I find spot metering helps quite a lot rather than evaluative, as you can pinpoint where you want to get the light from – the camera can be easily distracted by lots of stage lighting going off. Another good tip is to try to pick out particular band members with an attractive spotlight, so keep your eyes peeled.’

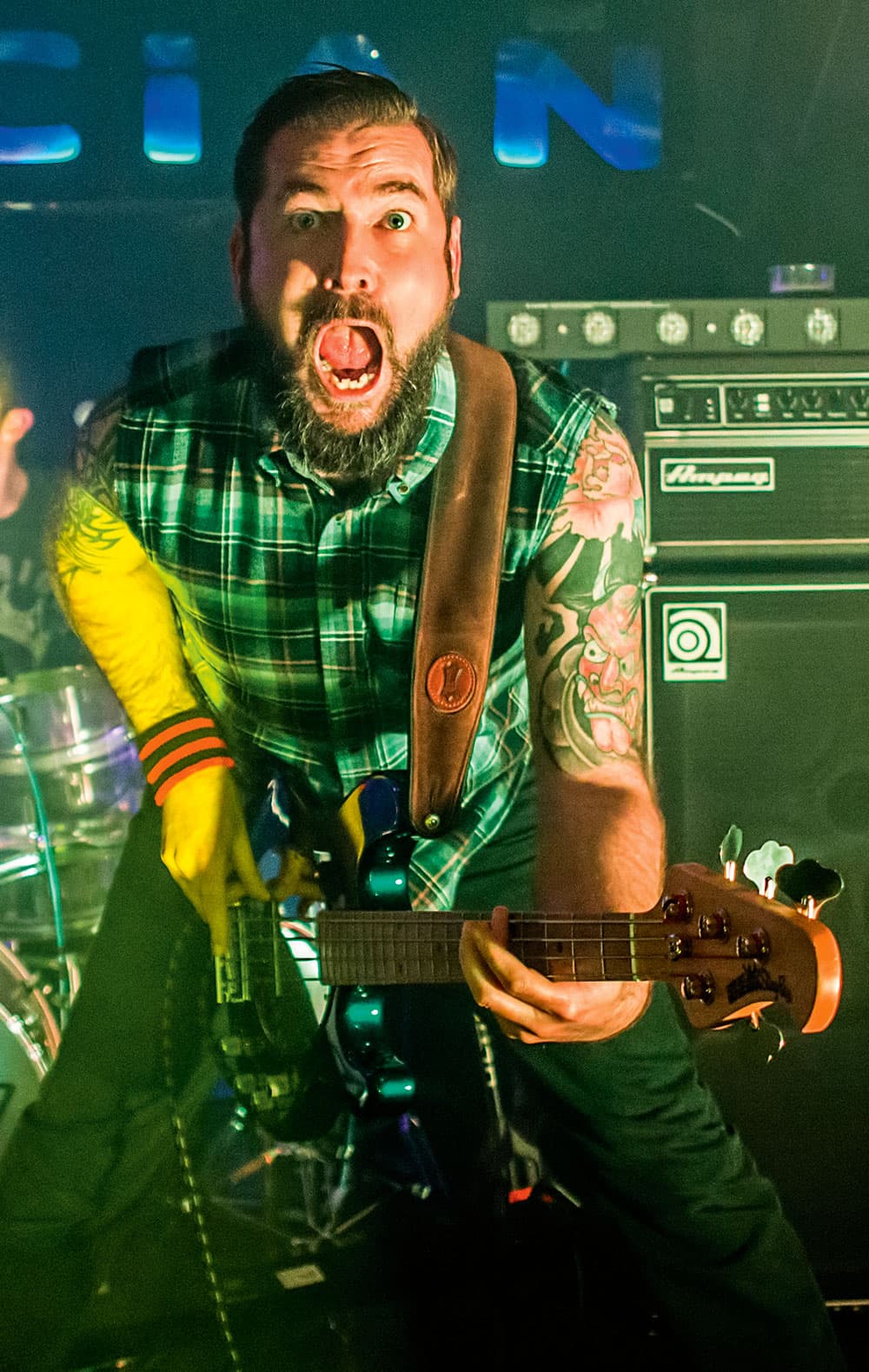

Cutt also makes an important point about composition and timing. ‘Carefully check facial expressions before you shoot – the singer won’t thank you if their eyes are half shut and they are pulling a weird face. It’s not attractive, but a “rock gurn” from a guitarist mid-solo is often OK. Try to get as much face as possible, hair permitting!’

Cardinal sins of composition

Effective framing marks out true skill in gig photography. Here are some rookie errors to avoid when it comes to composition.

- Watch the mics – singers with mics in their face rarely look good and these images are unlikely to make the band’s website or Facebook page. ‘No matter how experienced you are, mics in faces can be a real frustration of shooting in small spaces, both in terms of blocking and awkward shadows, and people do tend to fall foul of that a lot,’ says Trudi Knight.

- Watch what you chop – ‘it’s inevitable that you will need to make decisions about what’s important to include in a shot, but chopping legs off right at the knee, or losing half an arm and a fretboard can just look careless,’ she adds.

- Watch the background – another challenge with smaller venues. It’s frustrating bagging a great shot of a guitarist mid-solo, only to discover that the singer’s bum is in the background as they bend down to get a drink.

- Watch the stage furniture – big bulky stage monitors, amps and drum risers are also an eyesore best avoided. They can however add interesting angles and perspectives, says Shona Cutt. ‘Also be prepared to edit out signs in the background, like signs to the exit or toilet,’ says Shona. ‘Bands want to look cool, not like they are playing next to the loos!’

Shona Cutt

Shona Cutt is a Bath-based graphic designer and acclaimed music photographer who has shot The Darkness and Duff McKagan amongst others, as well as touring with The Answer. Check out her site at www.facebook.com/shonacuttphotography.

A typical rock gurn, but carefully framed and exposed. Canon EOS 550D, 24-70mm, 1/250sec at f/2.8, ISO 3200. © Shona Cutt