Untitled #70, 1980. This image formed part of Sherman’s early ‘colour experiments’ complete with back projection

It’s been nearly 40 years since Cindy Sherman started throwing on wigs, dresses, clown make-up and bodily prosthesis, and recording the variously glamorous and grotesque results through her camera lens.

Sherman’s work has found a home under a variety of banners: feminist, postmodern, or deconstructionist. Yet none of them seem quite capable of capturing the sense of her work. It’s a body of images that seems uneasy when contained within strict parameters.

This could well be a result of the artist’s own elusiveness. In interview after interview she sidesteps questions about the work’s theoretical underpinnings. As a result, the texts we have come largely from gallery owners, photography writers and academics, all of whom bring their own agenda to the table.

This book is no different. The intriguing introduction by Philipp Kaiser attempts to navigate the themes and ideas he sees within the work while also admitting that perhaps not all these ideas match the texts that have preceded it. With Sherman’s work it’s not enough to say, for example, that the images are feminist in context. Rather, we have to refer to the various ‘feminisms’ that have attempted to draw out meaning.

But this is not to say that Sherman’s work is without meaning – it certainly has several things to say. It’s simply that the truth of it may not necessarily be as complicated as some would like to believe. That’s not an insult to the work. I have a real feeling it’s something Sherman herself would agree with.

Untitled Film Still #47, 1979. This is one of Sherman’s early investigations into female tropes and stereotypes

Simulation and cinema

Untitled #92, 1981

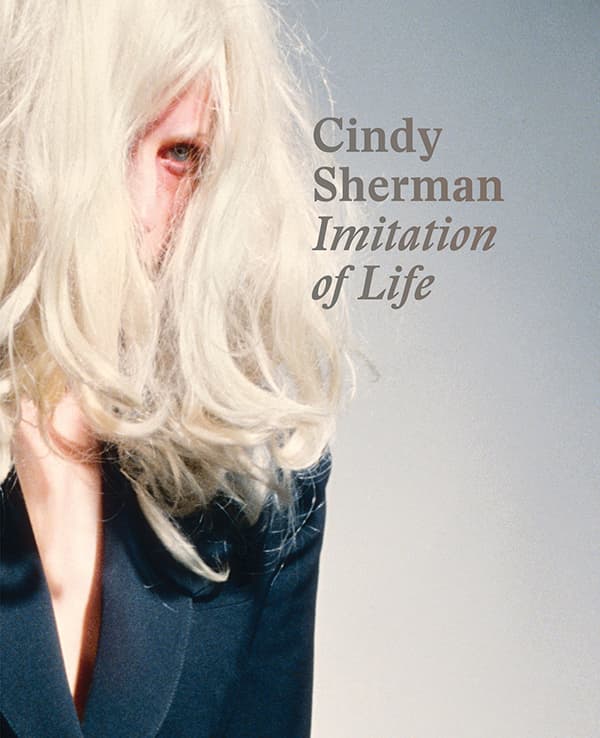

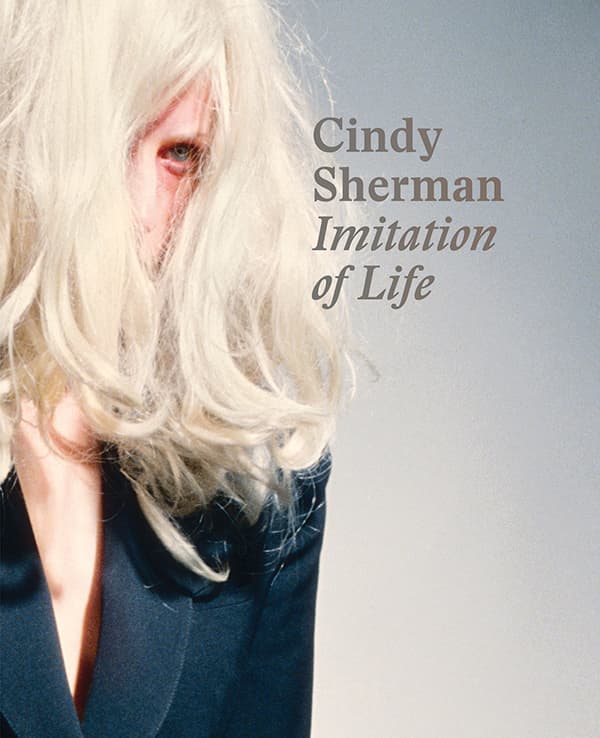

The title of the book, Imitation of Life, is said perhaps with some sense of irony. Sherman’s images are, in part, imitations of the characters, tropes and archetypes of the kinds of women we find in cinema and literature, many are which are simply male ideals of how women should appear. As many have noted, she is not imitating women, but rather images of women. Ideas such as the ‘male gaze’ and voyeurism are apparent in these early works, drawing as Sherman does from the publicity stills of old B-movies and Hitchcockian aesthetics.

The references to Alfred Hitchcock are important, not because she draws from the themes of the filmmaker’s oeuvre but because of the way she appropriates the viewer’s gaze, much in the way he did. It’s also important because we see how genuinely fascinated Sherman is with the field of cinema. Her ‘Untitled Film Stills’ series is a wonderful tribute and deconstruction of cinematic tropes. Look further into her work and you can spot her love of filmmakers such as Douglas Sirk and Sam Fuller.

The idea of imitation was something Sherman actually hit upon in her younger years as a painter. She found she had a natural talent for copying and it’s clearly a seed that infects much of her work as a photographer.

Imitation and simulation have a strong currency in the fields of academic studies, particularly in the work of Jean Baudrillard, and here we see those ideas transposed to Sherman’s images. But it’s a kind of imitation where we see the joins. Sherman’s work never attempts to reproduce exactly.

In many of the images we can identify the clearly constructed and considered sets, particularly when it comes to her ‘experiments in colour’, the images that make use of hokey back-projections. While these early colour images are often reproduced, it’s worth noting that they presented Sherman with her biggest technical challenge, especially considering how easy it was to wash out the projections with studio lighting.

Later, we see Sherman tackling women from history and women of contemporary society. The images are equally affecting and equally knowingly artificial. But for all the intertextuality, politics and deep themes, there is a level that can often get drowned out in the impenetrable reverie of the chin-stroking cognoscenti.

As Elizabeth Roberts, editor of Black+White Photography magazine noted in her review of this title, these images are fun and they are funny. Sherman knows how absurd and grotesque these images are. This is, after all, the photographer who appeared as a semi-parody of herself in John Waters’ film Pecker.

‘When I was in school, I was getting disgusted with the idea of art being so religious and sacred,’ Sherman said once, ‘so I wanted to make something people could relate to without people having read a book about it first. So that anybody on the street could appreciate it… That’s why I wanted to imitate something out of culture, and also make fun of culture as I was doing it.’ That sort of sums it up.

Score: 5 out of 5

Published by Prestel

Price £35, 160 pages, hardback

ISBN 978-3-79135-556-6